There is a watchmaker that creates one of a kind watches. Each watch represents a slow ticking of time and the individual philosophies and life stories of his clients.

Masahiro Kikuno is an independent watchmaker who designs, makes the parts for, and assembles watches almost entirely on his own.

Kikuno is one of the 31 members of the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants, an international association with the mission to perpetuate the art of independent watch and clock-making, based in Switzerland. He is the first Japanese person to be named a member.

His innovative approach to watchmaking incorporates traditional Japanese watches from the Edo period, or “wadokei,” which uses a temporal hour system to measure time, and has garnered worldwide attention.

Kikuno likens watchmanking to “writing poetry without words.” We asked him about his watches and his philosophies regarding time.

Only 18 watches sold in 10 years

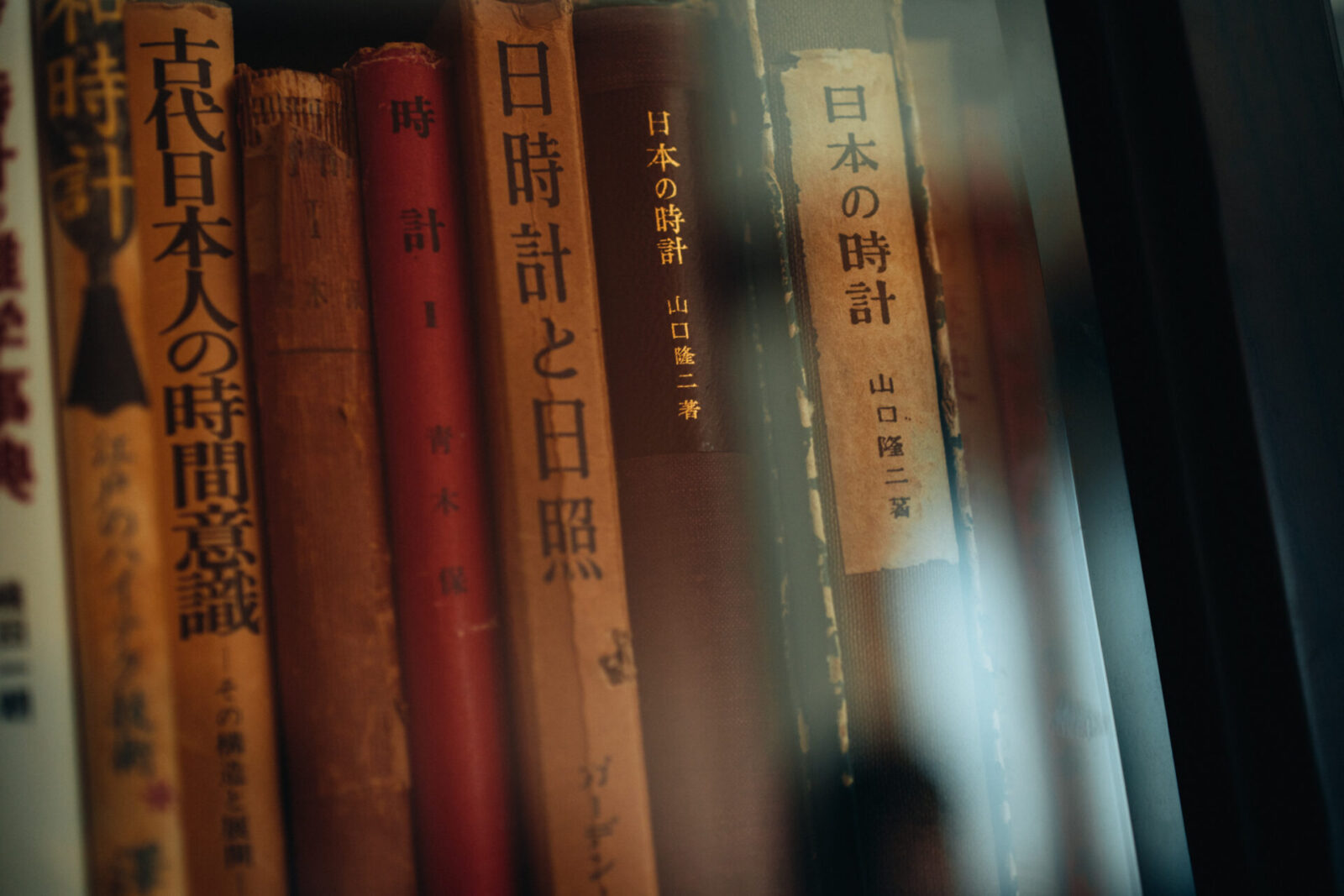

We visited him at his studio and home in Funabashi, Chiba Prefecture, where he invited us into his study-like workshop. From literature to biology, his bookshelves were lined with books of all genres.

The sound of the wall clock made in “wadokei” fashion creates a steady ticking noise. The space has a quiet and tranquil flow of time, away from the bustle and noise of the city.

It has been ten years since Kikuno began working as an independent watchmaker. In that time, he has only sold 18 watches.

Even if he spends months making a watch, he does not sell it unless he is completely happy with it.

Every new watch is a new challenge

The watchmaking process begins with Kikuno speaking to his client and learning about their life story and desires.

For example, his watch SAKUBOU is designed based on the phases of the moon. It was sold for 5.5 million yen.

The client traveled to Japan from abroad twice to meet Kikuno and they conversed through an interpreter.

Kikuno asked the client why they chose him to make their watch, what they value and their life philosophies.

After thoughtful conversation, he thought about how he can reflect the client into the design of the watch.

He was inspired to create a dial with a carving technique using “nanako-moyo”. It is a traditional Japanese pattern of small dots that resembles fish roe and is often seen in designs for sword decorations and Japanese cut glass work. If you look closely at the indexes on the dial, you find that there is no point at 6. He intentionally erased the number in the design to express numbers that the client said he cherished and his client’s beliefs.

Sakubou was designed to include the phases of the moon, and when the client requested to change the function of the moon phase into a dial that completes the rotation of the moon once a year, Kikuno created several design patterns and revised it numerous times before it was finalized.

The client also requested that their family crest be included in the design, so Kikuno designed the window that shows the phases of the moon with a cherry blossom motif based on their family crest.

Kikuno says that he tries new things based on the requests of his clients.

“There are ideas or challenging techniques that I would not have come up with on my own. It is part of the joy of creating something together with the client.”

“What is important is how much value the client finds in the product. There is no real intrinsic value, and there is no such thing as making a perfect watch. My hope is to create something that is close to what my client and myself envision as ideal.”

Kikuno also takes care to photograph the meticulous process of making each watch and creates an original photo book for each. When he hands over the finished watch, he gives the photo book to the client as a gift.

Kikuno’s “wadokei” series and the centuries-old temporal hour system

In Kikuno’s “wadokei” series, he uses a temporal hour system that was developed in the Edo Period which is unique to Japan.

Modern watches use a fixed time system where one day is divided in 24 hours. However, in the temporal hour system, day and night are divided into 6 equal parts, each of which are called “ittoki.”

Because the temporal hour system is affected by the length of daylight, the intervals of time change with each season.

For example, the “wadokei-kai” watch (priced at 19.8 million yen) pictured above, the indexes on the dial move automatically every day. The idea of the time intervals changing with the length of the day is expressed in the clock.

“For people who did farm work in the past, the temporal hour system was very useful. In Europe, people adjusted their lifestyle around the clocks, but in Japan, the clocks were adjusted to match the daily lives of each season. I think it would be interesting to try living under the temporal hour system today, even if it is just for the weekends or holidays.”

In our current industrialized lifestyles that value efficiency, living on a clock that is based on the sun and changes with the season may provide a different sensation of “time” itself.

Kikuno continued to share his thoughts on how drastically the way we sense time has changed.

“We used to correspond by letters. That changed to telephones, then emails, and now we use LINE. Now that we are used to this faster pace of communication, if I am even 10 minutes late to a meeting, I feel I have kept people waiting for a long time.”

“All of these technologies advanced for the purpose of helping people, but I feel we are now being led astray by them. The convenience of these things are in a way making us busier.”

Honing his skills in the Self-Defense Forces

Independent watchmakers are few and rare, even globally. So what led Kikuno to become an independent watchmaker?

Kikuno was born in Fukagawa, Hokkaido in 1983. From a young age, he loved building Legos and plastic models.

Naturally, he aspired to do craft work for a living, but did not like the fact that most manufacturing jobs were only involved in making a portion of the final product. He had a strong desire to build something from start to finish.

After Kikuno graduated high school in 2001, his first job was with the Self-Defense Forces.

“A recruiter for the Self-Defense Forces came to my high school and I learned that there were mechanical positions in the Forces. I thought it would be interesting to work on machinery that is usually unavailable in the civilian world.”

As he desired, he was put in a position that did maintenance work on rifles and guns, but first he had to overcome the harsh training of the Self-Defense Forces.

“The training was an important experience for me. I learned that everyone makes mistakes. For example, when one person in the group makes a mistake in training, everyone has to do push ups. Even the most competent people made mistakes. I learned that rather than blame people for failures, it is more important to think of ways to avoid future failures together.”

Kikuno gradually got used to his job as a mechanic, but grew bored of the manualized work. His desire to work as a craftsman to make his own products grew.

Around the same time, he found an unexpected growing attraction toward watches.

“My superior officer showed me his Omega Seamaster watch. I think he said it cost about 300 thousand yen. At the time, I was wearing a 1 thousand yen watch that I bought at the Self-Defense Forces store, so I was shocked that such an expensive watch existed.”

“Later, I found a magazine about watches at a bookstore. There were pictures of the springs inside of watches and it was the first time I found out about the existence of mechanical watches. I was surprised to discover this new world, and was fascinated at once.”

In 2005, Kikuno left the Self-Defense Forces and enrolled in a course specializing in watch repair at the Hiko Mizuno College of Jewelry in Tokyo.

The college only offered practical courses on fixing watches, but Kikuno was unable to contain his desire to make a watch from scratch.

He became fascinated by a TV documentary on the Myriad year clock, made by Hisashige Tanaka, a genius craftsman from the late Edo period and the founder of Toshiba Corporation.

These clocks were elaborate works of art, and they were renowned for their fine metalwork and mastery of Western clock technology.

“Seeing this clock was the first real shock. Compared to the period when these clocks were made, we have access to a lot more resources today. I realized it would be possible for me to make watches too.”

Kikuno graduated from college in 2008. Rather than finding a job, he remained at the college as a research student and immersed himself in watchmaking.

He started digging through papers related to clocks of the Edo period and began creating his own Japanese watches.

One day, his friend who worked as an interpreter introduced him to Philippe Dufour, a world-renowned independent watchmaker who agreed to take a look at his work. Kikuno took his handmade “wadokei” to Switzerland to meet Dufour in person.

Dufour was greatly impressed by Kikuno’s work and his detailed expression of traditional Japanese culture in his watches. He was also impressed by his ability to create watches using very limited machinery. Dufour invited Kikuno to exhibit his work at Baselworld, the world’s largest watch fair, in the following year 2011.

This meant that Kikuno would be joining the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants.

Kikuno shares, “To be honest, I hesitated for a moment.”

“I was unsure if I really deserved to make watches under such a prestigious title. There was doubt for a moment, but in the end I decided that no matter what kind of criticism I may receive, I really enjoy making watches and it is my desire to do so. Choosing not to make watches was not an option for me.”

It was this moment that Kikuno decided to live as an independent watchmaker.

Adhering to handmade watches

In the world of watchmaking, the labor is usually divided into different parts. However, an independent watchmaker does almost everything on their own, from designing and making parts to machining and assembly.

Kikuno insists that everything is handmade.

It is faster and more efficient to use a computerized automated machine, but he uses machines that are manually controlled to maintain the feel of working with his hands.

His carving machine is a good example. When he traces his desired design on the large drawing table, the machine carves a small version of that shape on his parts.

When shown the actual process of assembling the parts that he machined and adjusted in size, you can’t help but wonder in the face of its meticulousness whether a slight breath would cause it all to fall apart.

In his workshop, there were many well used tools that he used to make the elaborate watches.

Why does Kikuno insist on making his watches by hand and spending so much time on them?

“I think it is because I enjoy working with my hands. Usually, people talk about wanting to please the consumer. I think it would be a shame if the creator doesn’t enjoy the process of creation as well.”

What it means to craft the very best

To finish, we asked Kikuno what his ideal of craftsmanship is.

“I think crafting the very best means to make something that brings the most joy with as little resources as possible. It is good for people and the environment.”

“Hand making watches is not an efficient process, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t productive either. A small amount of metal pieces are put together and used around the wrist. There is a lot of skill, thought, and a unique story behind this small product, which turns it into something that is worth millions of yen.”

There is a refined and austere feeling in the air when Kikuno is making his watches.

His rich ideas and skills are truly outstanding.

Behind his crafts, there are numerous stories that have grown in a passage of time that melts together.

Photo:Kaori Nishida

Translation:Sophia Swanson

Born in 1990, Nagasaki. Freelance writer. Interviews and writes about book authors and other cultural figures. Recent hobby is to watch capybara videos on the Internet.

Editor. Born and raised in Kagoshima, the birthplace of Japanese tea. Worked for Impress, Inc. and Huffington Post Japan and has been involved in the launch and management of media after becoming independent. Does editing, writing, and content planning/production.