Tea is something that is a part of our daily lives. Whether it is accompanying a meal, or time spent enjoying a conversation with someone, or even during moments of quiet self reflection.

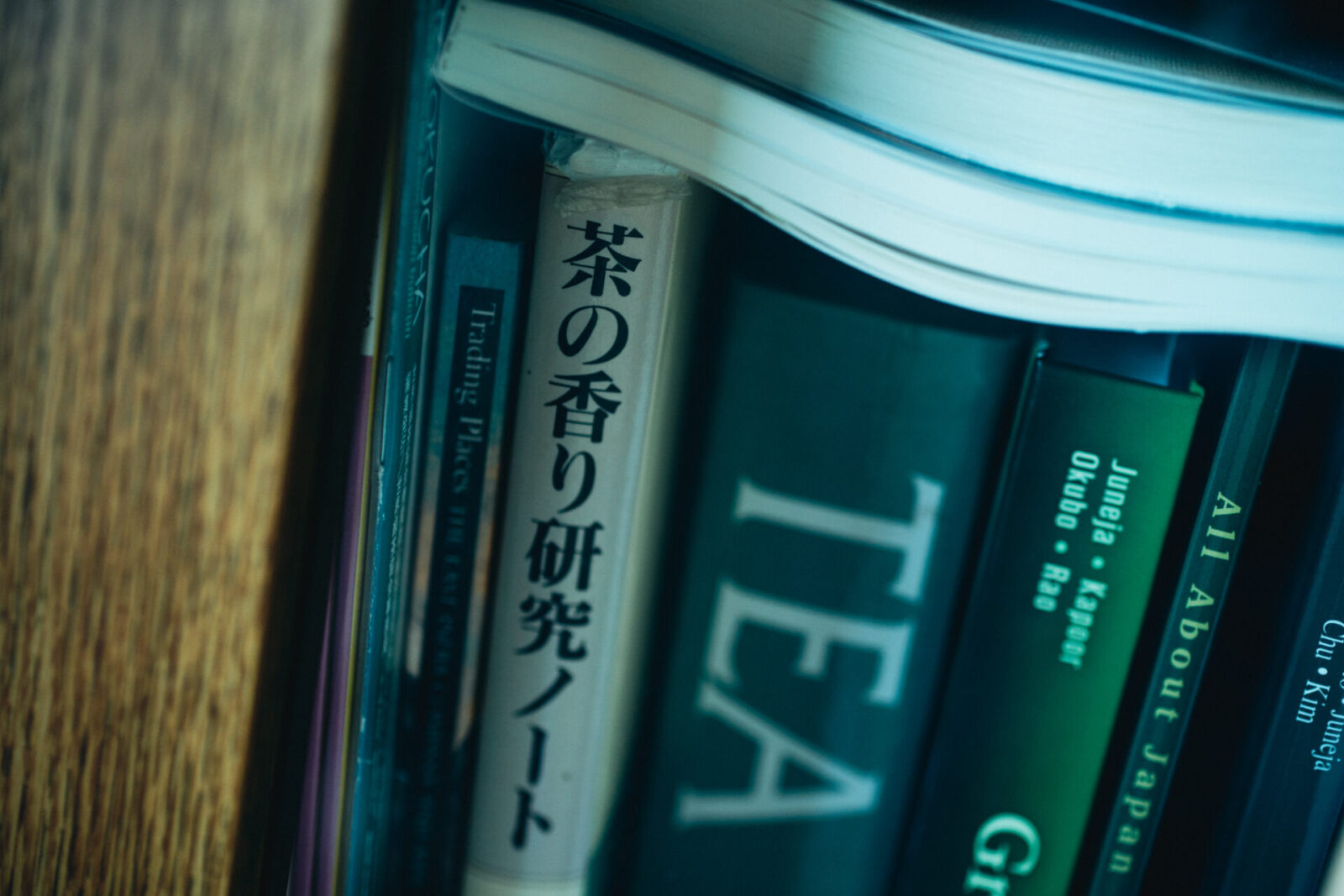

Professor Emeritus of Otsuma Women’s University, Dr. Masashi Ohmori is a deep admirer of tea and he has researched tea from a scientific point of view for many years. His research extends for 50 years and it has earned him the respected nickname of “Dr. Tea.”

Tea was first introduced to Japan from China during the Nara and Heian Periods. Over the years, it has become an integral part of Japanese culture and has been loved by the people for many generations. In recent years, however, production and consumption of tea has been slowly declining in Japan.

Nonetheless, Dr. Ohmori says, “Tea enriches our daily lives. It is a fascinating drink that has a lot of unknowns that we have yet to uncover.”

We talked to Dr. Ohmori about his lifelong research of tea, what drew him into the world of tea and his work, how to best enjoy drinking tea and what his vision for tea 100 years from now looks like.

How a coincidence led to 50 years of research

── You are known as “Dr. Tea” after studying tea for half a century. We heard that, in fact, you did not originally specialize in tea research. Is that true?

My introduction to the world of tea research was one by chance. When I was a student at Tokyo University of Agriculture, I was actually researching pesticides.

WhenI was a student in the 1960s, Japan was addressing major social issues from pollution related diseases such as the Minamata disease and mercury poisoning in the Agano River (Niigata Minamata disease).

As a student, I wondered if it would be possible to create a safer pesticide with low toxicity, unlike the organic mercury that was causing these adverse effects on the human body and the environment.

We collaborated with a food manufacturer to research the development of a selective herbicide that would kill weeds without having any effect on the crops.

── How did that lead to your research on tea?

I always knew I would pursue a career in research. I was invited by a senior colleague to join him at the National Institute of Health and Nutrition in Shinjuku, Tokyo, but by the decision of my research lab’s boss, I became a lecturer at Otsuma Women’s University. At the time, we did not really have the luxury of choosing our own career path after graduation.

After two years of working as a lecturer, Dr. Yataro Obata was transferred from Hokkaido University and became my new boss. I was about 30 years old at the time and Dr. Obata was 65.

Dr. Obata researched scents and was a very unique researcher. The first thing he did after he was appointed to his position in spring was to invite us to go see cherry blossoms with him. The cherry blossom season is mostly over in April, with the flowers already turning to leaves. However, as the petals fall to the ground after rain, they release a faint fragrance. We collected these petals and he told us to study its scent. He gave us all different and new ideas.

── He must have been a very influential teacher.

One day in May, Dr. Obata showed up with a traveling bag full of fresh tea leaves and told us, “Make black tea with these leaves.”

── He suddenly brought you tea leaves one day?

Deep down, I thought it was so out of the blue and I was not really interested. However, he was my boss and a researcher of higher rank. Furthermore, the tea leaves were fresh and raw so we could not just leave them be. I just answered, “Yes, sir.” and got to work.

My assistant and I immediately gathered books on the topic and began researching how to make black tea. We learned about the processes of “withering,” “rolling” and “fermenting.” However, we did not know how to actually do these processes.

While we were trying out different techniques with a mortar and pestle, all of the leaves started to mold. Dr. Obata came by and was furious when he saw the state of things, so we got a good scolding. (laughs)

As I did more research, I learned about the National Tea Research Institute (now the Kanaya Tea Research Station of the National Agricultural and Food Research Organization) in Shimada, Shizuoka. I went there right away and asked them to teach me about tea. The person in charge told me that Dr. Obata had visited them the day before. It turned out that Dr. Obata had gotten the fresh tea leaves from them.

An experiment in Sri Lanka that started it all

── I am surprised to hear that your introduction to tea was black tea and not green tea. What kind of research did you do from there?

At the time, Dr. Obata often said that he wanted to develop a black tea that could compete with Darjeeling and Ceylon tea.

An acquaintance of Dr. Obata, Dr. Tei Yamanishi, who was a researcher on tea fragrances, said, “Tea fields in Sri Lanka looked bright red.” Dr. Obata hypothesized that there might be a red yeast and beta-carotene that helped bring out the fragrance of the tea.

From that point on, I visited the research lab in Shizuoka twice a week and continued my research.

Later, with the cooperation of the TRI (Tea Research Institute) in Sri Lanka, I was able to conduct some experiments with beta-carotene on site at the home of black tea.

Our experiments produced a black tea with an incredibly wonderful aroma.

Each tea estate in Sri Lanka has its own unique flavor and aroma. The teas are tasted by buyers and priced at an auction. The buyers have developed keen senses to judge the quality of the black tea leaves. They know all of the scents and flavor characteristics of each estate.

── It sounds similar to wine tasting.

The buyers who tasted our tea responded very positively. However, because the flavor was different from the usual tea leaves made at the estate, the final judgment was that the tea was not as good as the harvest of previous years so it was assessed at a lower price.

It was a big loss for the estate who provided us with the plantation to conduct our experiment. It was also the first tea that I produced and shared with the world, so although I was excited about it, it never saw the light of day and that was very disappointing.

Still, the seed to my interest in tea was planted and it remained thereafter. Before I realized, it has been 50 years and here I am today.

There are still a lot of things I don’t understand, but I have been addicted to studying tea ever since.

The story behind Gabalong tea

── Speaking of innovative developments, you developed a new type of tea in the 1980s.

In 1986, I developed the Gabalong Tea at the tea research institute of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan. The tea was developed when we were researching ways to preserve tea for longer periods of time.

In the song “Chatsumi (tea picking),” there are lyrics that read “88 nights until summer.” In tea harvesting, the new tea leaves are called “shincha (new leaves)” and the first harvest is called “ichibancha (first tea).” This harvest occurs on the 88th day (in early May) after Risshun, which is the first day of spring.

To process the green tea, the picked leaves are steamed. However, if too much is harvested at once, the process of steaming cannot keep up.

On the other hand, if you wait too long to harvest, the leaves will become hard and the quality of the tea will decline. We were wondering how to address this problem and took a hint from the process of anaerobic treatment used in transporting foods.

When transporting fruits and vegetables to distant locations, nitrogen gas is used during transport to prevent oxidation. This is known as anaerobic treatment and to explain it in simple terms, it is a method that preserves freshness by not allowing the plants to breathe.

── I see. So you tested to see if anaerobic treatment can be used for tea leaves?

When we put the freshly picked tea leaves through anaerobic treatment right away, we found that the leaves could be preserved without altering its flavor. However, we also found that the most important aroma was negatively affected. It had an intense smell that was similar to that of a damp towel being left in a plastic bag for a long time.

Since we went through the trouble of making this tea, we analyzed it anyway and found that the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), a type of amino acid, was 10 times higher in the tea leaves than in normally processed tea leaves. In 1963, there was a study that found that GABA lowers blood pressure.

With a sense of anticipation, we conducted an experiment on rats with high blood pressure and found that the tea lowered blood pressure in these rats. We were able to prove the effect through clinical experiments, but we did not yet understand the mechanism of why it lowers blood pressure.

For the time being, we named the tea containing large amounts of GABA the “Gabalong Tea” and presented it at an academic conference. The name came from combining Oolong, which was gaining popularity at the time as a health-inducing tea, with GABA.

── I understand that you did not patent the manufacturing process of Gabalong Tea, so anyone can produce it.

While the domestic production and demand for tea is declining in Japan, we wanted to somehow contribute to the tea industry in a meaningful way.

However, the intense odor of the tea gave it a bad reputation. In order to address this problem, we tried roasting the tea using a technique called kettle roasting. The moderate roasting of the tea helped turn the smell into a pleasant aroma.

In order to promote Gabalong Tea, I established a venture company within the university. However, we still have a long way to go to revitalize the tea industry as a whole.

Production on the decline, and envisioning the culture’s future

── The domestic production volume of tea was over 100 thousand tons in 1975, but that reduced to 80 thousand tons in 2020. Unfortunately, the production and consumption of tea in Japan is declining as a whole.

During the period of high economic growth, tea production volume was still growing. Domestic production peaked in 1970 and has been declining ever since.

We believe this is in part due to changes in the Japanese diet, the declining population with the decreased birth rate, and the changes in our everyday lifestyles.

Many tea growers have chosen to change crops because tea production is not profitable. The same is true for tea merchants. During the period of economic growth, there were about 2000 tea merchant shops in Tokyo alone, but when I studied the numbers 3 or 4 years ago, there were only about one tenth the number remaining.

Japan has a long history and tradition when it comes to tea culture. However, no matter how good a tea is produced, if those qualities are not promoted adequately, the demand for Japanese tea will not return.

If we remain stuck in our old business practices and simply complain about failing sales, of course we will only continue to decline. The industry needs to come together and work as a whole in order to improve the quality and functionality of tea or the culture of tea in Japan may all but be lost.

On the other hand, tea is a growing market when you look at the world as a whole, and matcha has become very popular worldwide. I think it would be great if we can move to improve our techniques and quality of tea so that we can expand sales of tea for not only matcha, but also bancha teas to overseas markets.

── Although drinking canned or bottled tea has become more popular, fewer households are brewing tea at home and that is leading to lower consumptions as well.

I believe that the production of bottled tea by beverage manufacturers has become one way that ensures that tea is not forgotten and remains in our daily lives.

However, the amount of tea leaves used in a 2 liter bottle is only a few grams. Compared to brewing tea at home, the consumption of tea leaves is inevitably less. The production of bottled tea has maximized the efficiency of using tea leaves so it makes a big difference.

On another note, more and more restaurants are offering fine quality teas to accompany meals for their customers who cannot drink alcohol. I think this initiative is also a good one for preserving our tea culture.

However, if only high-end products survive in the market, the past advantage of green tea being an accessible drink will be lost and it may be difficult to increase demand. This is why I hope that new techniques will be developed to make serving and enjoying tea easier, and as the benefits of tea become more clear, that people’s interest in tea will increase once again.

── What do you think of using tea for purposes other than drinking?

Recently there has been increased research in utilizing tea in ways other than consuming it as a beverage. Bath salts, incense, candles and other products utilize the fragrance of tea. There is even a plywood that has been developed that uses tea tree wood and leaves. Research on using tea in beauty products and skin care is also underway.

One time, I used boiled down tea to make a hair dye for my gray hair. If you add an emulsifier and oil, it becomes like a pomade. Unfortunately, my hair dying endeavor was not well received. (laughs)

In 100 years, will tea still have a place in people’s hearts?

── What do you think the tea culture in Japan will be like in 100 years?

My hope is that it will still be an integral part of people’s everyday lives.

There are many different kinds of tea in the world, from green tea, oolong tea to black tea. All of these teas come from the same camellia sinensis tea plant. It is believed that these plants originated in the Yunnan Province of southern China.

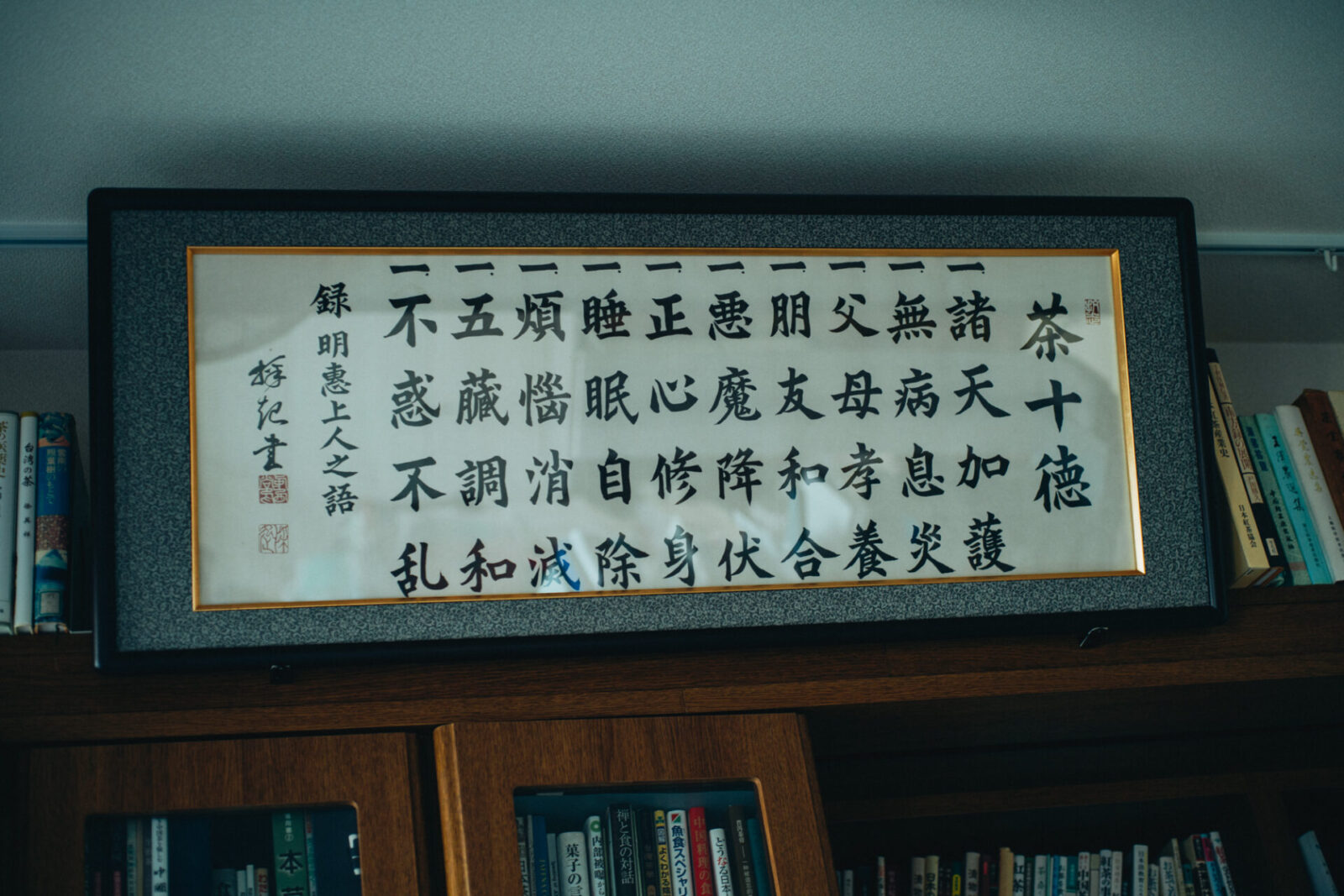

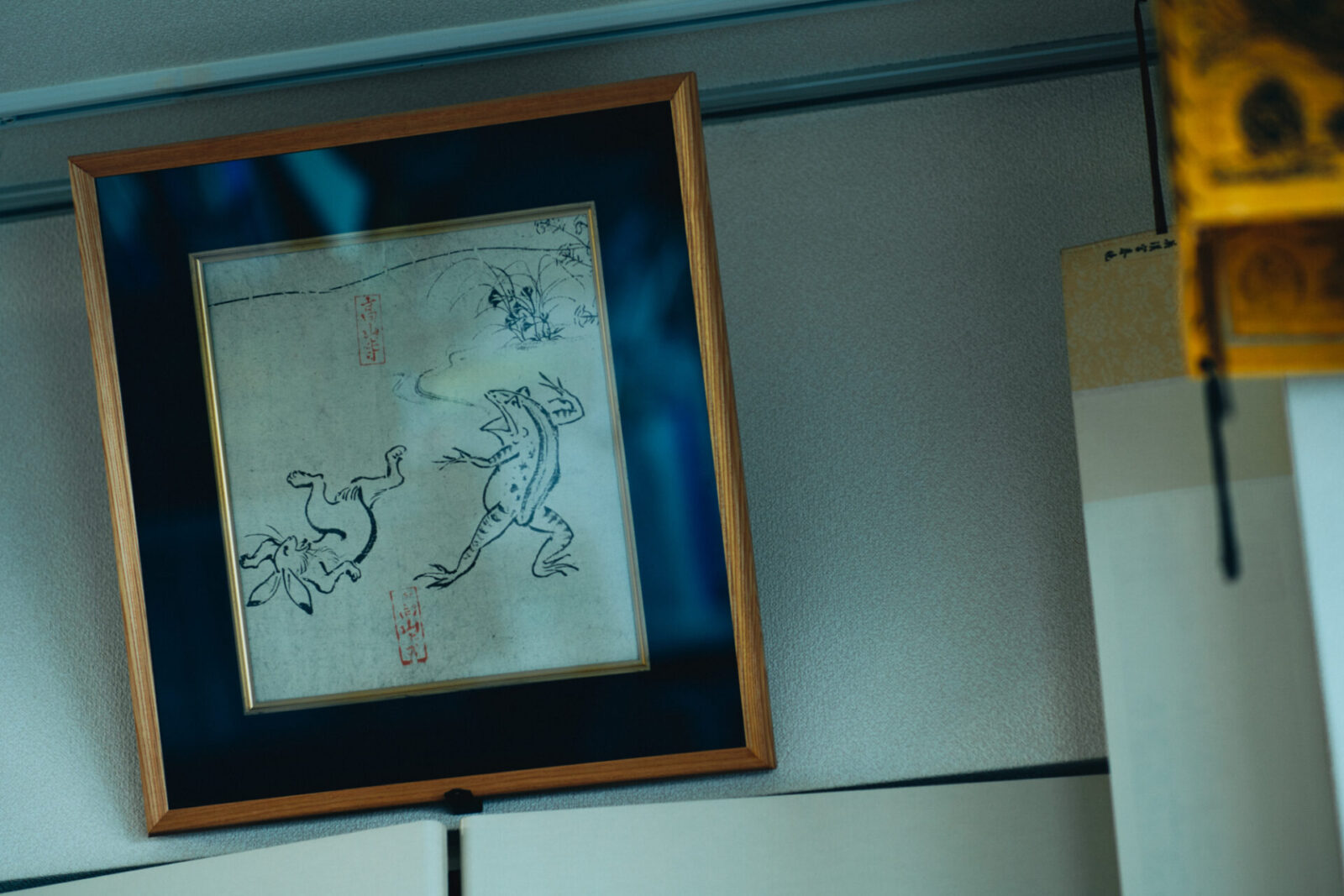

Around the 8th century during the Tang Dynasty in China, a man named Lu Yu, known as the “Tea Sage,” wrote the world’s oldest book on tea, “The Tea Sutra.” According to this book, the detoxifying effects of tea were recognized and have been passed down through generations from about 5000 years ago.

It is said that tea was introduced to Japan between the Nara and Heian periods. The production of tea is said to have started in the Kamakura Period when Zen Master Eisai brought a tree back from China and planted it on Mt. Sefuri in Saga Prefecture. Ever since, tea production and tea culture have spread throughout Japan.

Even today, tea and the lives of Japanese people are inseparable. We often drink tea with breakfast and lunch. Food is central to one’s physical and mental health.

In order to promote tea and keep it as a beloved staple food in our lives, I believe that it is necessary to convey the importance of a well balanced diet that includes tea.

── You have studied and loved tea for half a century. How do you think we can better our relationship with tea?

Even after traveling to China, India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and other parts of the world in search of the historic roots of tea, and drinking many different types of tea, there is still a lot that I do not know myself.

We are learning more about the catechins, caffeine, and amino acids in tea and the effects and benefits they have on humans. However, we still do not understand the mechanisms as to why they are beneficial.

To put it bluntly, we know it is good for our bodies, but we don’t know why it is good for us. That is what makes it interesting.

I want to continue studying this question of why and how tea is beneficial to us. I think the most important thing for scientific research is to keep being curious and to keep pursuing answers to questions.

While it is important to look into the benefits and functions of tea, it is also important to enjoy tea itself.

In the past, many households lived with their grandparents, but as the nuclear family became more common, there are less family gatherings in our lives today. More people are living alone and many of my students tell me that they do not have a teapot at home.

I believe that spending time with people you are close to while drinking tea is a universally enjoyed passtime. Drinking tea alone and having time for self reflection is also so. These are very rich ways to spend our time.

Even if it is only once a week, if we can take our eyes off our smartphones and take a moment to sip a cup of tea that we brewed in a teapot, I am sure it will provide a sense of peace. I truly hope that our tea culture will remain preserved and passed down to future generations.

How to make delicious tea, as taught by Dr. Tea

First cup

Put about 15 grams of tea leaves in a teapot and pour 150ml of cold water. Wait for 15 minutes and pour into a tea cup. Enjoy right away or cool in refrigerator overnight before drinking.

Second cup

In the teapot with the tea leaves still in it, pour in 150ml of warm water that is about 50°C. Wait 1 minute and then pour into a tea cup.

Third cup

Pour 150ml of boiling water into the teapot with the remaining tea leaves. Wait 1 minute and pour into a tea cup.

The first cup is called “mizudashi (cold water brew)” and has a delicious flavor and sweetness with an umami similar to Japanese soup stock. The second cup has a refreshing aroma and astringency that is typical of tea. The third cup has a soft bitterness. With the same tea leaves, it is possible to enjoy three unique and completely different flavors.

Reference: The trends in green tea consumption (supply basis) in Japan

National Federation of Tea Production Organizations and the National Federation of Agricultural Cooperatives of Tea Producing Prefectures

https://www.zennoh.or.jp/bu/nousan/tea/seisan01a.htm

Photo:Kaori Nishida

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Reporter for Business Insider Japan. Born in Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo. Taught world history as a high school teacher, worked for Huffngton Post Japan and BuzzFeed Japan before assuming current position. Interests incude economics, history, and culture. Covers a wide range of topics from VTuber to Rakugo and is interested in food culture from around the world.

Yuko Souma is the director of Delightful LLC and was born in 1976 in Chichibu City, Saitama Prefecture. Souma began their career working as an assistant to editor and writers at a production company while studying at Waseda University’s Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences. In 2004, Souma was an editor and member of the launch team for the free magazine R25 at Recruit Co., Ltd. They left that role in 2010 and has since produced and edited for magazines, books, online publications, booklets for corporations and municipal governments, and owned media.