The arrival of spring brings the start of the first harvest season for green tea leaves, called “shin-cha” or “new tea.” The fresh green of the tea leaves which withstood the fierce cold weather of the winter are vibrant and vigorous and the rich and fresh aroma of shin-cha is a specialty that can only be enjoyed for a short time each year.

What is the process of producing and delivering shin-cha to our tables?

In 2022, the DIG THE TEA team will travel with Ryo Iwamoto, a tea ceremony master and CEO of Japanese tea startup “Tea Room,”, to visit various tea plantations around Japan and discover the unique scenes of shin-cha production. Our first visit was to the biggest tea producing region in Japan: Shizuoka. We followed the cycle of how the first harvest of green tea is picked, processed and distributed to reach our tables for enjoyment.

A tea loved by one of Japan’s most prominent warlords

We met with Iwamoto at the JR Shizuoka Station, where we started our journey by heading north.

After a 20 minute drive from the inner city, we were soon within sight of the bright green tea plantations that spread out over the mountainous slopes.

Motoyama is located in the upper region of the Abe River, a Class A river that flows through Shizuoka City, and the Warashina River basin. It is one of the most prominent tea production areas in Shizuoka.

It is said that the tea from Motoyama was offered to Ieyasu Tokugawa as the “Imperial Tea” tea during the Edo period (1603-1867). Ieyasu, who was known as an avid tea enthusiast, is said to have had the tea from Motoyama stored in a tea warehouse in the Igawa region, where the shin-cha leaves picked in spring were stored, matured and enjoyed until autumn.

When Japan opened its borders to foreign trade and the Port of Shimizu opened in the Meiji Era (1868-1912), tea cultivation in Shizuoka expanded rapidly. By the Taisho era (1912-1926), tea from this area came to be known as “Motoyama Tea,” signifying that the tea was authentic tea from the mountains.

The Moriuchi Tea Plantation’s centuries-old craft

The first tea plantation we visited was the Moriuchi Tea Farm, which has a history that dates back to the Edo Period. The plantation has been run by the family of Yoshio Moriuchi, the current owner, for nine generations. He and his wife, Masumi, work together to manage the three hectares of tea plantations scattered on the steep slopes of the surrounding mountains.

The Moriuchi Tea Farm is known for growing about 15 different varieties of not only green tea, but also fermented teas such as oolong and black tea. They also hand-pick their shin-cha tea leaves without using machines, and their tea has been highly appraised at numerous tea fairs and competitions.

any people from all over Japan come to visit Moriuchi to learn about tea. Moriuchi welcomes all his visitors with warmth and hospitality. Our visit with him also started with an offer of freshly brewed tea.

2022, a tough year for shin-cha production

Our visit to the Moriuchi Tea Farm was at the end of April and the shin-cha picking season was just beginning. Moriuchi told us how he had just spent all morning picking tea leaves.

He told us about the lookout of the shin-cha quality for this year’s harvest.

“The tea plants feed off the rain that falls in February and March and that is when the new leaves grow at once. However, we did not have very much rain during these months this year so the new leaves did not grow well. It will be a tough year for us tea producers. Our harvest volume will be less than it was last year, but I think the flavor will be richer because of it.”

The growth of new tea leaves changes drastically each year depending on the weather. Although the harvest volume will not be satisfactory this year, Moriuchi says he will focus on bringing out the aroma of the tea leaves to its fullest by using their machines that are designed to replicate hand rolling techniques that have been passed down through generations.

Moriuchi explains, “Although we mostly use machines now, all the rolling was done by hand in the past. Once the process starts it can take up to six hours, but hand rolling is the best way to preserve the shape of the tea leaves without crushing them.”

In Shizuoka, there are eight styles of hand rolling techniques that are preserved and passed on through an organization called “Preservation Group for Tea Hand Rolling Techniques.” In the Motoyama region, a style known as “Houmei-ryu” has been passed down through the generations.

A drink with an ever-growing fan base

The Moriuchi Tea Farm also takes part in Tea Tourism, where they accept visitors to tour their plantations and give workshops on how to hand roll tea leaves. Before the coronavirus pandemic, there were roughly 500 domestic and international visitors each year and they enjoyed tasting the various teas made by Moriuchi in the cafe space set up in the farmhouse.

Moriuchi says, “A single variety of tea leaf can be turned into anything from sencha, to fermented teas such as oolong and black teas. After the tea leaves are harvested, there are multiple ways to approach the final product. I personally enjoy listening to everyone’s thoughts as they taste the different teas.”

Moriuchi’s tea is not only popular among overseas visitors, it also grasps the interest of young people.

“We had students from the Shizuoka Professional University of Agriculture visit us as a part of their school curriculum. We have them taste various teas and when we ask which one was their favorite, they always choose one. This helps them realize their preferences and even the shy and silent students start to speak up and ask to buy a certain tea. I think that tea is a drink that has the potential to have an ever-growing fan base just by offering different opportunities to experience teas.”

The secrets hidden in Shizuoka’s unique terrain

After we left the Moriuchi Tea Farm, we headed further north. Our next stop was The Craft Farm factory in the Okochi district of Shizuoka City, which is in charge of research and development of the tea leaves sold at TeaRoom, and also does the first and second processing of their tea products.

When we arrived, the tea plantations were covered in a light mist and we could hear the chirping of a Japanese bush warbler in the distance. The surrounding landscape created a mystical sight.

The reason why Shizuoka became one of the biggest tea producing regions in Japan is because of its unique terrain. The surrounding and overlapping mountains often form fogs in the region and limit the amount of direct sunlight. Under these conditions of scarce sunlight, the tea plants are unable to photosynthesize so they store amino acids which transform into delicious flavor.

When you look out into the tea plantations before the first harvest is picked, you can see how the new leaves, which are soft and full of life, are growing out of the tips of the bushes. It is as if they are awaiting the moment of harvest.

When we arrived at the factory, located about a 10 minute drive away, they were in the midst of starting the first processing of the shin-cha harvest of the year.

Iwamoto explains, “Tea leaves start to oxidize soon after they are picked so it is important to pick them gently and deliver them to the factory for processing as soon as possible. Upon arrival, we immediately process the leaves into ‘aracha’ or ‘crude tea.’”

The process of making crude tea means that they will reduce the water content of the picked tea leaves to 5 percent. Doing this first process in a factory near the tea plantations reduces the amount of oxidation.

Iwamoto took us through the factory to show us the actual process of turning the freshly picked tea leaves into “aracha.”

The color and fragrance of “aracha”

The tea leaves that are carried into the factory were picked just a few hours before. The room is filled with its fresh and clear scent. When you pick up a bundle in your hand, they are slightly warm and close to the temperature of human touch.

Fresh leaves oxidize and ferment quickly, so in order to preserve their freshness, the first step is to lower the temperature of the leaves by cooling them down with very moist air.

The next step is steaming the tea leaves. The tea is passed through a tube-shaped machine that heats them up and stops the oxidation process while preserving the green color.

The length of time the tea leaves are steamed, from “light steaming,” “normal steaming” to “deep steaming,” changes the color, flavor and scent of the tea, so it is an important process which determines the final flavor of the tea.

After the tea leaves are steamed they go through a repeated process of rolling and drying.

First, the tea leaves go through a machine called “soju-ki” which roughly rolls the leaves. Air is sent to cool down the leaves as they are rolled. The tank inside the machine rotates like a washing machine, stirring the tea leaves inside.

Next, a large brush-like machine rolls the tea leaves in a sideways motion in what is called a horizontal roll. These specialized machines are called “jyunen-ki,” which means “rolling machines,” and as they roll the tea leaves they squeeze out the excess water from inside.

Iwamoto explains, “The reason why we repeat the processes of horizontal and vertical rolls is because tea leaves used to be rolled by hand. The machines are designed to replicate that movement as closely as possible.”

Seeing the massive machines reproduce the labor that used to be done by hand makes one realize the incredible amount of human labor this process had required in the past, and it puts us in awe.

The next process is called “chujyu,” where the tea leaves undergo further rolling under hot air. The final process is called “seijyu” where the tea leaves are delicately rolled into a fine shape.

Two brush-like arms rotate in the machine to circulate the tea leaves. This forward and backward rolling movement creates the signature needle-like shape of Japanese green tea.

By this point, the tea looks nothing like the original fresh leaves.

To finish the process, the tea leaves are dried in hot air to reduce its water content to 5 percent. After the stems and brown leaves are removed, the “aracha” is complete.

Iwamoto explains, “The process between the arrival of the fresh tea leaves to the completion of the ‘aracha’ is about eight hours. The leaves are harvested in the morning and the factory starts processing them in the afternoon. After all the processes are complete, the workers work through the night to clean the machines and prepare for the next day’s work. This routine is repeated day in and day out until the shin-cha season is over. It is not uncommon for the workers to bring a sleeping bag and sleep over at the factory during the harvest season.”

Observing the processes involved in making Shin-cha made us realize how much of a race against time it is to lock in the maximum flavor, color, and aroma of the freshly picked tea leaves.

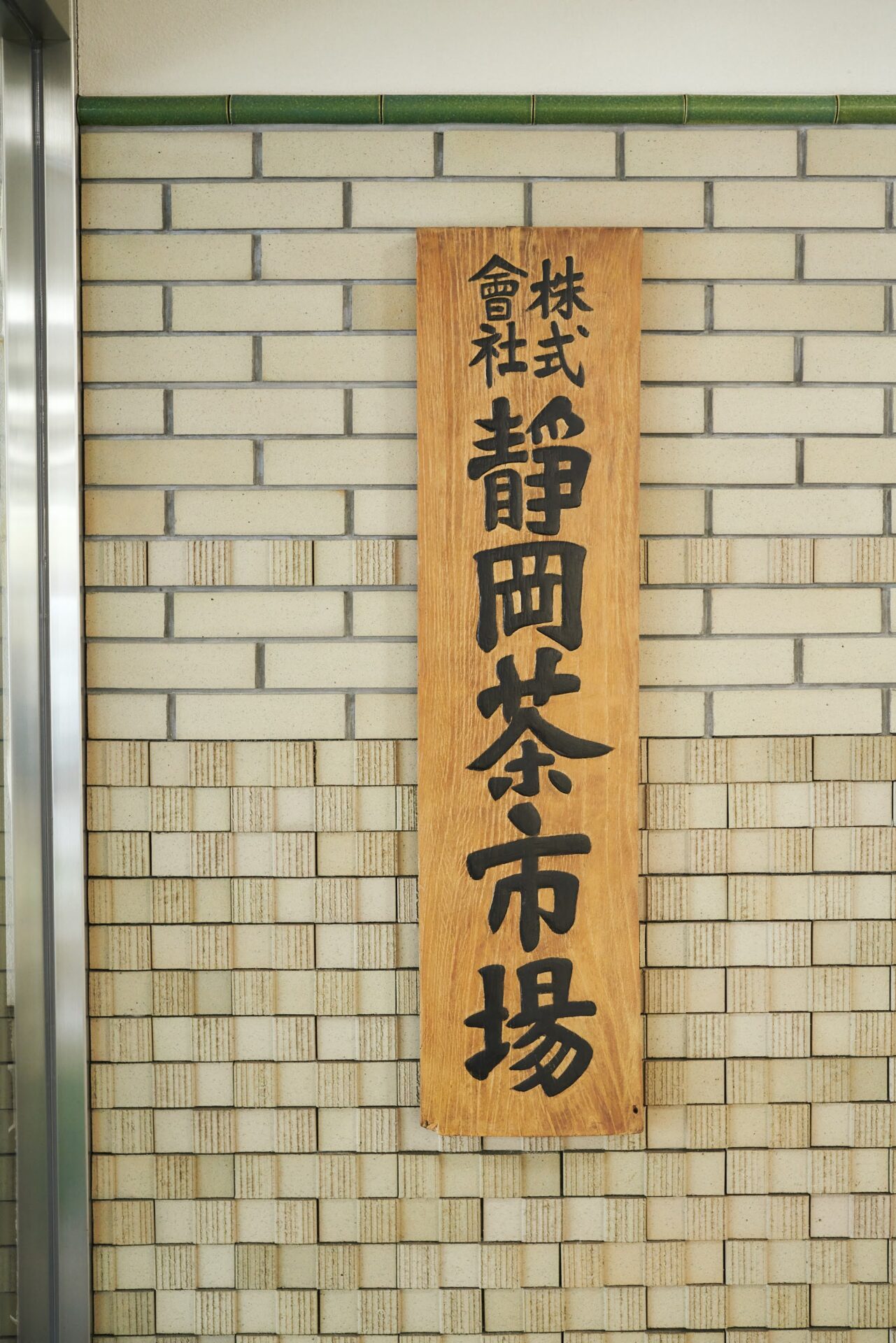

The Shizuoka Japanese Tea Market, a central part of the tea trade

Our final stop was a visit to the Shizuoka Japanese Tea Market, which is the first tea trading market that was established in Japan. “Aracha” from both Shizuoka and all around Japan are gathered in this central tea market and this is where they hold the negotiations and transactions that determine the price of the teas.

Early in the morning, tea leaves from various tea growers are put out on display at the market and they undergo inspections to check the quality of the tea before the trading commences.

Buyers go around to the inspection boxes to first check the shape and color of the tea leaves with their eyes, the texture with their hands and take the leaves up to their nose to check the scent. Later, they pour hot water on the leaves to check the aroma and flavor to decide which tea they will negotiate to buy that day.

The buyers only take about one minute to assess the quality of each tea. The process requires many years of experience and a keen eye for aesthetics, as the quality of the tea and the manufacturing process must be determined in this very short time.

When trading time starts, the buyers go to negotiate for the teas that they put their eye on. However, the buyer and seller do not negotiate directly and the transactions are mediated by an employee of the Shizuoka Japanese Tea Market. This method of negotiation serves to facilitate the transaction from a neutral standpoint and prevents extreme soaring or falling of the tea prices.

Every year, the market is filled in an air of excitement and tension, especially during the Shin-cha season. After a transaction is successfully completed, there is a custom where the seller, buyer and market employee clap their hands together three times in unison. It is an old custom, and the reason why they clap three times is because the number three has always been considered a lucky number in Japan.

The more ways you know how to describe tea, the more enjoyable it becomes

Iwamoto is a producer of tea himself, but he is also a wholesaler and distributor, so he inspects teas from around all Japan almost everyday.

He showed us the process of inspecting tea.

まFirst, the tea leaves are placed on a balance and weighed at 4 grams. The amount of tea leaves is standardized in order to ensure that tasting is done under the same conditions for all the teas. We are told that a mere 1 gram increase in the amount of tea leaves will bring out bitterness in the aroma of the tea.

Next, the tea is put in an inspection bowl that is filled with 200 milliliters of boiling water.

“Generally, it is said that tea is best brewed at 60 to70 degrees Celsius. However, while brewing at a lower temperature brings out the sweetness of a tea, using boiling water brings out the aroma.”

The dried, needle-shaped tea leaves return to their original leaf shape when seeped in hot water. At the factory, we observed the process of turning the fresh leaves into dried tea leaves, but inside the inspection bowl, it was as if we were observing that process being reversed.

The tea leaves that have opened up again are picked up using a small net and carried to the nose to take in the scent. Holding the net at a slight angle makes the steam from the tea leaves rise directly up your nose so the aroma passes through smoothly.

After the aroma is appraised, the bowl is lifted to the mouth to check the flavor.

As we watched Iwamoto inspect the tea, we noticed that he described the tea in many ways besides the regular words such as “sweet” or “bitter.” Interestingly, he used words that seemed unrelated to tea, such as comparing it to aroma oils, seaweed and even milk.

“Many people from other countries tend to describe tea like they describe wine and their vocabulary to describe flavor and scent is very rich. For example, if one were to say it has a flower-like scent, they go on to describe that scent as being floral or citrus-like. If we can enjoy drinking teas in a way that explores different flavors, I think it will expand the experience of the world of tea even more.”

The “aracha” that goes through inspection at the Shizuoka Japanese Tea Market is then distributed throughout Japan. From there, they are blended with different varieties, undergo the final light roasting and are delivered to our tables as the final “tea” product.

From the tea plantations, the factories and then distribution, the process of making shin-cha involves the work of a lot of people.

The harvest volume and flavor of shin-cha is determined by the winter weather. The making of “aracha” which locks in the color and aroma of the tea leaves, is a tradition that can only be experienced in springtime Japan.

As we welcome the arrival of spring, we rejoice in another successful season of shin-cha and enjoy the new tea. This beautiful custom of tea happens throughout Japan and our “journey to discover shin-cha” will continue at DIG THE TEA.

Photo: Umihiko Eto

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Local writer / editor. Born in Osaka, currently living in Fukuoka. Worked in advertising at Recruit Co. before becoming freelance.

Travels around Japan interviewing and writing about regional communities, crafts, and relocating. Involved in various regional projects and is a voice of the local people and their work. Author of Hanro no Kyoukasho(EXS Inc.)

Editor and creator of the future through words. Former associate editor of Huffington Post Japan. Became independent after working for a publishing company and overseas news media. Assists in communications for corporates and various projects. Born in Gifu, loves cats.