Wasabi is an integral part of many Japanese dishes such as sushi and soba.

With its pungent flavor and refreshing spiciness, it is a very unique food product that is unlike anything else in the world. The ingredient is unique to Japanese cuisine and is deeply integrated in the Japanese diet.

Fujiya Wasabi Farm has been cultivating wasabi for more than 100 years in Azumino, Nagano Prefecture where there is abundant spring water that is sourced from the melted snow of the Northern Alps.

Keichi Mochizuki is the fourth generation director of the Fujiya Wasabi Farm and he is thinking outside the box to promote Azumino wasabi to the rest of the world.

We spoke to him to learn more about the characteristics and cultivation of wasabi and his endeavors of promoting the Azumino wasabi brand as a luxury herb of Asia to the world.

Azumino is a unique region for wasabi cultivation that is blessed with endless spring water

On a hot day in the peak of summer, we visited the Fujiya Wasabi Farm drenched in sweat. Upon arrival, we found the farm to be pleasantly cool with remarkably clear spring water flowing freely at our feet.

We could feel the cool spring water temperature through our rubber boots.

Mochizuki told us that the water is safe to drink, so we scooped up the water in our hands and took a gulp. The cool water was delicious and quenched our parched throats and we felt refreshed and revived.

It was surprising to learn that there is such an abundance of clear, clean water here.

“If you take a close look at the ground, you will see that there are bubbles coming up here and there. We do not draw our water from elsewhere but we use the natural spring water of this land. There is spring water everywhere in Azumino.”

Wasabi cultivation requires an abundance of soft, clear and clean water. The desirable water temperature is about 12~13℃.

Shizuoka is another region that is known for wasabi cultivation, but the wasabi there is cultivated using a “tatami-shiki” method. In this method, the wasabi is grown in terraced fields on a slope and mountain spring water travels from the top of the mountain down the terraced slopes and eventually flows out to the rivers below.

The wasabi farms in Azumino use a cultivation method known as “heichi-shiki” (flatland method). Azumino is surrounded by steep mountains and the subterranean water from the Alps flows beneath the ground here. They say that wherever you are in Azumino, if you dig two meters into the ground you will reach spring water.

Azumino is the only region in Japan that utilizes underground spring water to grow wasabi in this way.

Azumino spring water washes away the pungent components of wasabi

“When it comes to wasabi, there is no season or particular time of year when it tastes best. It usually takes about two to three years for a stalk to grow before it is harvested. There are streaks in the stalk that represent the number of seasons and years it spent growing.”

“The part that we grate and eat is called the “potato” and is part of the stem called the rhizome. Rather than growing downwards, the stem grows upwards so the older parts of the potato are at the bottom, while the younger part is at the top. This is why the wasabi will taste different depending on which part of the potato section you eat.”

The bottom part of the wasabi has a stronger pungency and the upper part is more fresh and contains more water.

The wasabi plant is constantly producing its pungent flavor as it grows and that pungency also causes the plant to weaken. This is why it is essential for fresh spring water to be constantly available to wash away its pungency.

The pungency especially accumulates in the roots, but in regions like Azumino where the wasabi plant is constantly being exposed to clean spring water, the pungency gets washed away.

This makes Azumino’s unique environment ideal for wasabi cultivation.

“The water of this region is really special and important for our cultivation. Wasabi does not grow in hard water, and the temperature of the water is also important. At the same time, wasabi needs careful human care in order to grow well. You can find wild wasabi in the mountains, but they don’t grow this big.”

At the Fujiya Wasabi Farm (or Azumino Wasabi Farm), the wasabi are shipped whenever the individual plant reaches its peak. Wasabi can be planted any time of the year, so fresh wasabi is available year round.

Only 20% of Japanese people have tasted real wasabi

“I think that maybe only 20% of the Japanese population have eaten real wasabi. Perhaps most people will never know what real wasabi tastes like.”

Mochizuki makes this shocking statement with little hesitation. What does he mean by it?

Although Azumino is the second largest producer of wasabi in Japan, along with Shizuoka Prefecture, the annual production volume is only about 800 tons (including all the parts of the plant). That is less than the equivalent of one day’s production volume compared to other vegetables. If you count only the potato of the plant, the production volume is a mere 200 tons. Currently, the production volume of domestic wasabi is less than the consumption volume of wasabi in Japan.

“Wasabi cultivation in Azumino started 150 years ago, but the volume of production has not changed since then. Even if we wanted to increase production, it would be very difficult to do so. There are only so many areas where wasabi cultivation is possible, and we are limited within that land space.”

Most of the processed wasabi that is available in Japan is made from imported horseradish. Although they sometimes mix in some domestic wasabi stems, the grated potato (rhizome) part is almost never included.

The allyl isothiocyanate, which is the pungent component of wasabi, is also found in the plant’s stems and leaves. Mochizuki says, “The processed products of wasabi are an important method that allows Japanese people to use wasabi on a daily basis.”

However, the potato part of the wasabi plant is a rare and expensive product that is sold to sushi restaurants, Ryo-tei (traditional Japanese restaurants) and other high end restaurants.

The stems, leaves and roots of the plants are all used in processed wasabi products, so very little of the plant goes to waste.

Japan has a long history of appreciating wasabi

Although wasabi is an integral part of Japanese food culture, most people know surprisingly little about it.

Wasabi is a perennial plant of the Brassicaceae family and is native to Japan. In the wild it grows in mountain valleys and streams with clean water, but it is hard to find.

There is a long history of wasabi consumption in Japan. A wooden inscription found in the remains of a court in the Asuka Period (between 538~710) has the inscription 委佐俾三升 (wasabi sansho). Wasabi is also mentioned in the Honzo Wamyou, which is Japan’s oldest encyclopedia of medicinal plants written in the Heian Period (794~1185).

It is clear that wasabi has always been an important medicinal plant since ancient times.

It is said that wasabi cultivation began in the early Edo Period (1603~1868). Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu was very health conscious and so knowledgeable about medicine that he mixed his own medicinal herbs. He was also a food enthusiast and there is a famous anecdote about how he was once served wasabi from Utogi (current Shizuoka City) during his stay in the Sumpu Castle and took such a liking to it that he declared it a treasure. Utogi was said to be a wasabi growing region and Tokugawa Ieyasu likely had a large influence in turning Shizuoka Prefecture into the major wasabi producing region it is today.

Azumino of Nagano Prefecture lines up with Shizuoka as a leading region for wasabi production, however, its history surrounding wasabi cultivation is not as clear. It is said that cultivation here started about 100 years ago.

It is said that wasabi was first planted in the waterways used to drain fields to grow pears, which were common in Azumino, and it turned out that wasabi grew very well there.

Wasabi was first only grown for private consumption, but thanks to the development of a railway that opened up train access to Tokyo in 1902 and allowed for quick and direct shipping, it was found that wasabi could be sold at considerably higher prices than pears so the cultivation of wasabi gradually expanded.

Azumino is made up of a composite alluvial fan (formed when several layers of deposit are developed from the flow of multiple rivers). The area located at the tip of this fan is where spring water from the Northern Alps gushes out from the underground. The Azumino Wasabida Springs Park is designated as one of Japan’s Top 100 best water springs.

About 700,000 tons of spring water flows out each day and the temperature remains almost constant year round, never exceeding 15ºC.

This unique geography of the region made rice cultivation difficult in the past and was a cause for a lot of hardship, but it turned out to be an ideal region for wasabi cultivation.

Discovering the appeal of his family’s wasabi farm while majoring in agriculture

Mochizuki was born and raised as the fourth generation son of a family run wasabi farm, but growing up he says that he did not help in the farm and had a carefree childhood.

“I think I was very spoiled growing up. My family was very easy on me.”

When he entered university he started working part time at an izakaya (Japanese style pub). He discovered that it was very hard work, but the pay was not as much as he had expected.

“It was at this time that my father told me, if you become a wasabi farmer you will be able to make more money and live more luxuriously. After that I was easily convinced to take on the family business. I think if they had made me help on the farm as a kid, I would have resisted more and not taken on the family farm. (laughs)”

Mochizuku studied at an agriculture school for college and he says it was rare to be from a wasabi farm so even his classmates took an interest in him. He learned that wasabi can only be grown in certain environments and realized how special it was. He decided he wanted to share its appeal more to the world.

Promoting wasabi to the world

Partly because Mochizuki was not aware of the common customs of wasabi farmers, he was able to experiment and implement his original ideas and started leading wasabi cultivation in a new direction.

In the past, wasabi farms were closed to the public and farmers did not let many people into their farms. Mochizuki says that even in Azumino, many local people do not know how wasabi is really grown.

Mochizuki changed the convention of the wasabi industry by inviting chefs and other visitors into his farm and teaching them about the plant itself. He also exchanged information and ideas with them.

Mochizuku is also sure to visit and eat at the restaurants that use his wasabi.

“Professional chefs are always very respectful of farmers and our stories. I was happy to learn that after they come and visit my farm, they share what they learned with their customers.”

Mochizuki also goes out of his way to appear in various media. The social media sites that he started to promote wasabi overseas have also garnered a lot of attention and are growing in followers.

His posts often include comical videos on the reactions of various people from different countries tasting wasabi. These videos are one reason his sites have attracted viewers and popularity.

Overseas exports of his wasabi have been expanding and he says he receives many visitors from all over the world at his farm in Azumino.

Wasabi is now being used as an accent ingredient in French and Italian cuisines and is valued as a rare and luxurious spice from Asia.

Mochizuki also promoted wasabi in England and France by using it in cocktails to make a specialty drink.

“We made a mojito-like drink using grated wasabi. When wasabi is used in a drink the flavor becomes very refreshing and not as pungent and the drink was really well received.”

“When I told a sushi restaurant about that experience, they made me a drink called Namida Sake which is made by adding wasabi to sake. I think wasabi today has a very limited image of being used only for sushi and soba, so I wanted to expand the use of wasabi. I feel that there is a lot of potential for wasabi in mixed drinks.”

Developing an original grater just for wasabi

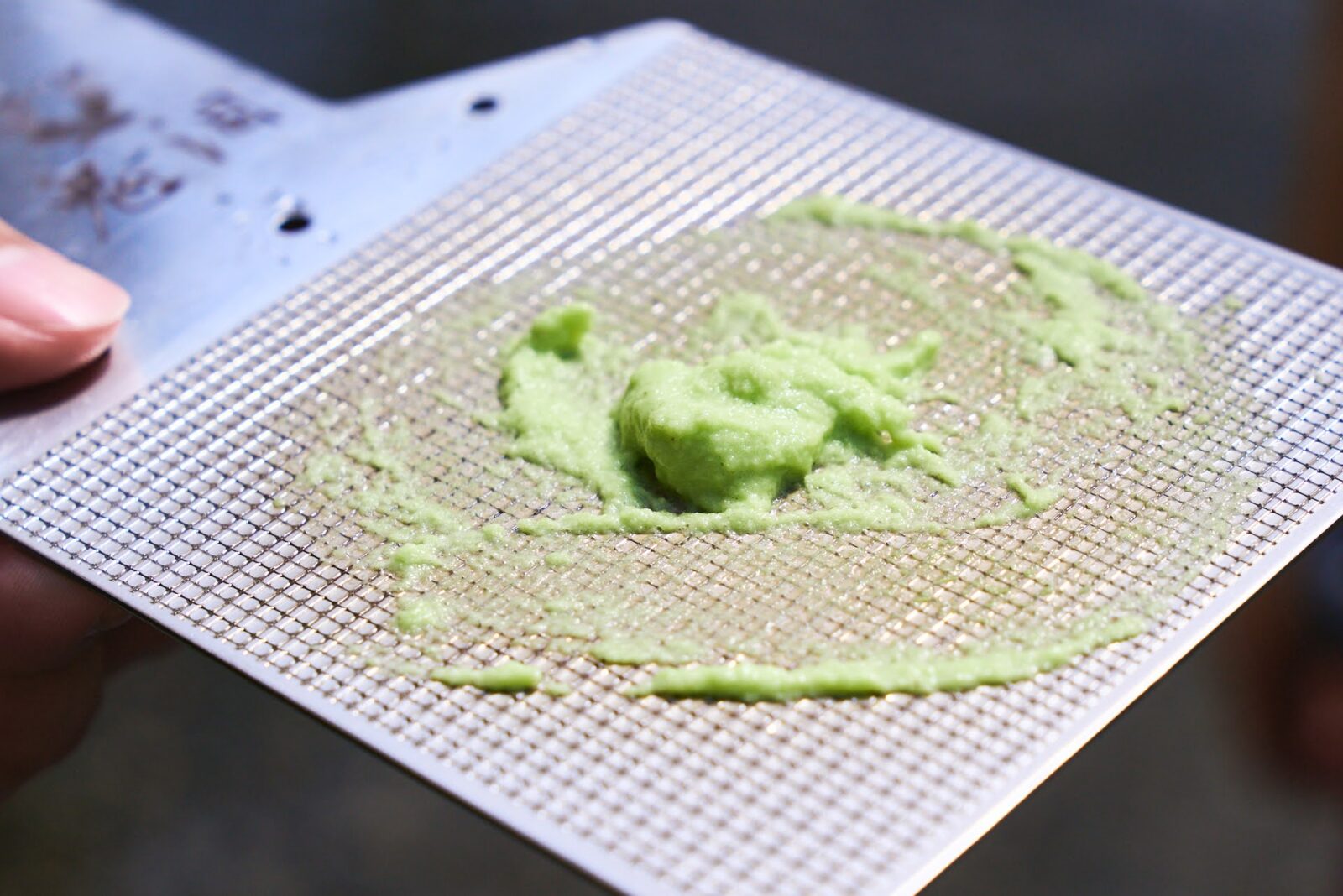

Mochizuki also came up with the idea to develop a new and original grater just for wasabi.

He worked with a factory in Suwa, Nagano and thoroughly researched the sharkskin grater which is commonly used for grating wasabi. Based on his research, he developed an original grater that produces superior results for wasabi.

“We researched which part of the sharkskin grated wasabi the best and applied that to the entire surface of our grater. When using sharkskin, there is an inconsistency in the results because it is uneven in certain places so if you use it everyday the surface gets clogged up and the grater won’t last more than a year. With our grater, it creates an even result no matter where you grate and it doesn’t clog so it can be used for a long time.”

“There are some countries that don’t allow the import of sharkskin products, but our products can be exported anywhere. Our product helps make the wasabi very soft and creamy.”

We tasted the freshly grated wasabi. At first there is a pungent and refreshing spiciness that is characteristic of wasabi, but later it is followed by a fruity and sweet flavor.

Mochizuki says that the sweetness is similar to persimmons and that his wasabi has a sugar content of about 16 degrees brix.

The fresh and clean flavor is reminiscent of Azumino’s natural environment.

“Most of the wasabi that is grown in Azumino is sold directly to restaurants and food makers so it is not sold in regular markets. I don’t think you will even find it in the Toyosu Market. The wasabi here is not as well known as the wasabi from Shizuoka, so our brand power is still weak. My goal is to raise the market value of Azumino wasabi.”

“Azumino is the only place in Nagano where wasabi cultivation is possible and it is also the only place in Japan where the flat land cultivation style we implement is possible. I want to better utilize this unique and special environment that we are blessed with and promote Azumino more.”

A new project to produce domestic caviar utilizing the abundant spring water sources

Mochizuki is working on another new project lately, which is to farm raise sturgeons. What seems to be an unexpected project is in fact a way to further utilize the natural spring water of Azumino.

“I had caviar at a sushi restaurant once and began researching sturgeons. I figured I could farm them myself. It’s a difficult challenge as it takes eight years just to start producing eggs, but I’m finally entering my fifth year.”

“Not only is the caviar delicious, but sturgeon meat itself tastes like sea bream and makes a very nice sashimi. The spring water of Azumino also helps raise a delicious fish. Sharks develop a strong ammonia-like smell because they don’t have kidneys. Sturgeons, on the other hand, are an older breed of fish so they can break down ammonia and don’t retain that smell. They also don’t bite because they don’t have teeth and are really gentle fish.”

Mochizuki’s next big goal is to develop a sushi that originates in Azumino, using his wasabi, sturgeon fish and caviar.

While making the most of all the blessings of Azumino’s land, Mochizuki aims to develop his high-end wasabi and sturgeon farm. His vision and projects to take on the world is just beginning.

Click here for all articles exploring BOTANICALS

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Advisor to corporations, and local governments on promoting local tourism. Published work includes, “Aomori & Hakodate Travel Book” (Daimond), “San’in Travel: Craft and Food Tour” (Mynavi), “A Drunkard’s Travel Guide: Sake, Snacks, and Tableware Tour” (Mynavi). Her life work is to explore towns in her travels, drink at different shops and visit the workshops of different crafts. Interests include tea, the Jomon period, architecture, and fermented foods.

Editor. Born and raised in Kagoshima, the birthplace of Japanese tea. Worked for Impress, Inc. and Huffington Post Japan and has been involved in the launch and management of media after becoming independent. Does editing, writing, and content planning/production.