MONPE are traditional monpe (working pants for women) redesigned into modern looks.

The monpe are made of a light and comfortable fabric called Kurume Kasuri, a traditional Japanese fabric which has been used for over 200 years in the Chikugo region of Fukuoka Prefecture.

Their colorful designs include solid colors, strips, polka dots and various other eye-catching designs.

The Unagi no Nedoko(meaning “eel bed”) is a local trading company for cultural products based in Yame City of Fukuoka Prefecture and they are involved in a wide-range of businesses, such as product development, sales, and PR. They add original designs and unique ideas to cultural items from the local region, and have created products that are fun and playful.

We visited Yame City to find out more about Unagi no Nedoko’s history and the new scenes created by MONPE, or what they call the “jeans of Japan.”

Visiting Unagi no Nedoko in Yame City

Unagi no Nedoko is based in the south-western region of Fukuoka Prefecture.

They renovated traditional Japanese-style houses which are now home to three of their shops. The Old Terasaki House is a cafe and local crafts store, the Old Marubayashi Main Housestore sells originally developed products such as the MONPE, and the OHAKO Old Otsubo Tea Shopexhibits artwork.

First, we visited the Old Terasaki House.

After entering through the Adachi Coffee cafe space, you take off your shoes and enter the shop area. The goods are sold in three sections: clothes, food, and housing. Items range from tableware, shoes, toys, and other household items that embody the culture of the region.

Next to the neatly lined up goods, there is a short introduction of the creator of the product. It is impressive how each product is individually exhibited, like artwork. You get a strong sense of how much they are rooted in the local community.

At regional cultural trading companies, everyday items share a common trait

What is a regional cultural trading company?

Shiramizu explained that regional culture is “a phenomenon that emerges from interactions between the people and land of a certain region.”

There are unique regional cultures that do not receive a lot of attention from the greater public or have very little information available about them on the internet. This company is working to bring such cultures to light and share them with a larger population.

Unagi no Nedoko has three criteria for the products they sell at their shops: regional characteristics, craftsmanship, and local economy.

Shiramizu stresses the importance of the local economy, which is the backbone of culture. One can sense his pride in his trading company from these words.

“Craftsmen are often talked about in a romantic way, like they are saviors protecting traditional cultures. But the truth is that they are individual members of society that need to make a living. The biggest reason craftsmen become unable to continue their craft is economical.”

“If you don’t sell or buy products, people will not take interest. For example, there is only a small population of people who enjoy going to museums to just look at something. However, a much larger population is interested in the popular TV show that appraises antiques.”

“When something has a price tag, it can be seen as part of your daily life. I hope to connect people through daily goods and increase the number of people who are interested in regional cultures.”

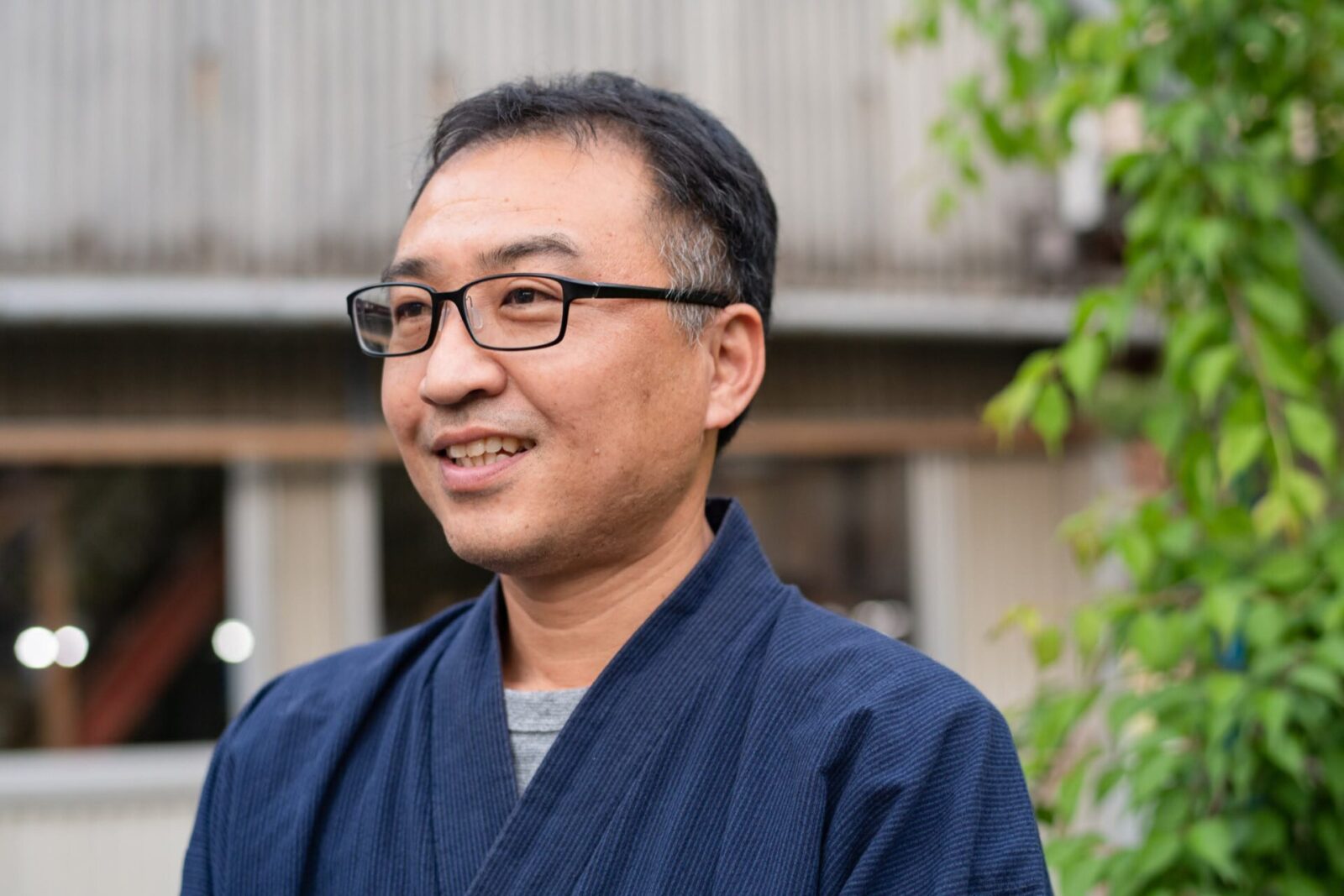

Studying urban planning, and founding Unagi no Nedoko

Shiramizu was born in Ogi City of Saga Prefecture. He studied architecture and urban planning at Oita University. Since his years in school, he felt the importance of pursuing ways to “find new value in existing things.”

“About 15 years ago, there was a surplus in housing so there was no shortage in buildings.”

“It was around this time that the Real Tokyo Estate (a real estate website that specializes in renovated properties) was founded and the MIKAN Architects (an architectural firm) began working on renovations. My classmate Haruguchi (co-founder) and I talked about how it would be better to use an existing building rather than build a new one.”

After graduating university, Shiramizu attended a design school in Fukuoka and by chance became the chief promoter of the Kyushu-Chikugo Genki Project, a job creation project by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare to create jobs in regional areas.

“My initial desire was not necessarily to sell goods, or even make a statement. However, as I met various craftsmen I was struck at how unfortunate it is that their very interesting work wasn’t receiving any recognition.”

“I had lived in Kyushu for over 20 years, but I realized there was so much I did not know. Through products, I want people to learn about this region’s activities and the characteristics of the land.”

Because he was in charge of branding and product development for the region, he met many residents of Yame City.

In 2012, a newspaper interviewed them about an event they planned in Yame City, and they were asked what their company name was. Shiramizu thought about it for a day and came up with the name Unagi no Nedoko because their office building was an old Japanese nagaya (traditional row house).

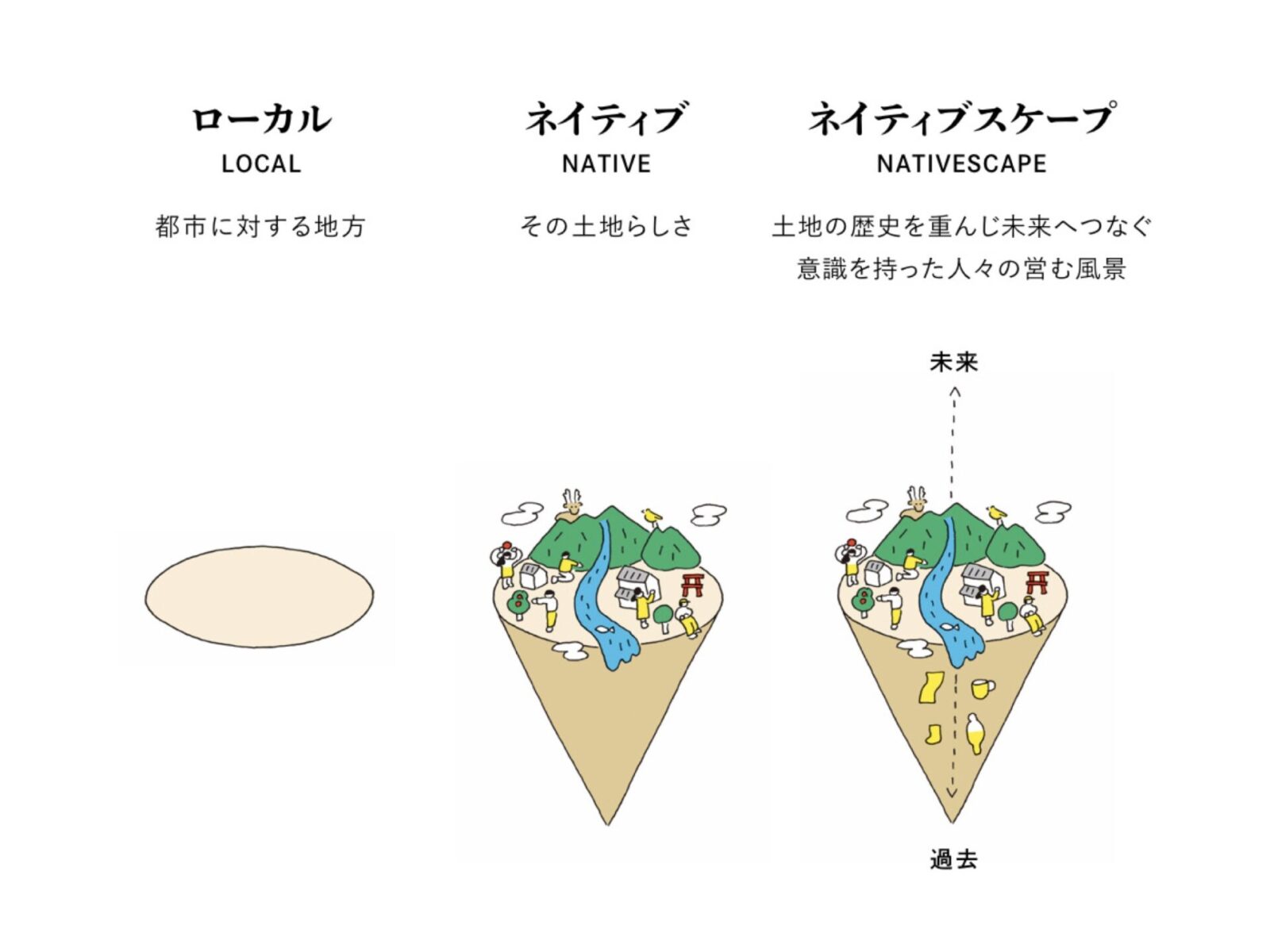

The difference between “local” and “native”

Japanese culture, such as foods and arts, are often described with the word “local.” However, Shiramizu insists on using the word “native.”

“Local is a word used by the city to describe regional areas. They identify all regional areas under that one word and don’t pay attention to the uniqueness of each region.”

“Oftentimes, the government will describe traditional arts as having value because ‘it has always been part of that region.’ But it is not clear what they are comparing this to. I think that goods and cultures have value because they are unique in each region.”

“I define this confirmed uniqueness as being ‘native.’ I also call the environment where people who understand these past histories and traditions are working to actively pass it on into the future as “nativescape.”

What is the vision of Shiramizu’s nativescape?

“The global supply chain is a system that can realize production and distribution without the representation of the people involved. However, ‘nativescape’ shows the individual faces of the people involved, from the production of materials all the way to consumption.”

“I am not saying that the global supply chain is a bad thing, but I believe that it is important to realize a society where we have a choice between the two.”

The comfort of MONPE becomes the “jeans of Japan”

MONPE, which was born from Shiramizu’s idea, is a product that is emblematic of the “native” concept. Shiramizu explains how he came up with the idea.

“My wife’s family business was in making Kurume Kasuri fabric. I did not know much about Kurume Kasuri fabric and simply thought of it as the cross pattern clothes that people used to wear during the war.”

“When I visited a regional shop in Yame City in 2011, I happened to find Kurume Kasuri monpe pants on sale. I tried some on and found that they were really comfortable. I realized then that a lot of people might be interested in them.”

Shiramizu organized an event called Monpe Exposition at the traditional arts center in Yame City where his wife worked. The event attracted TV media and newspapers and garnered a lot of attention.

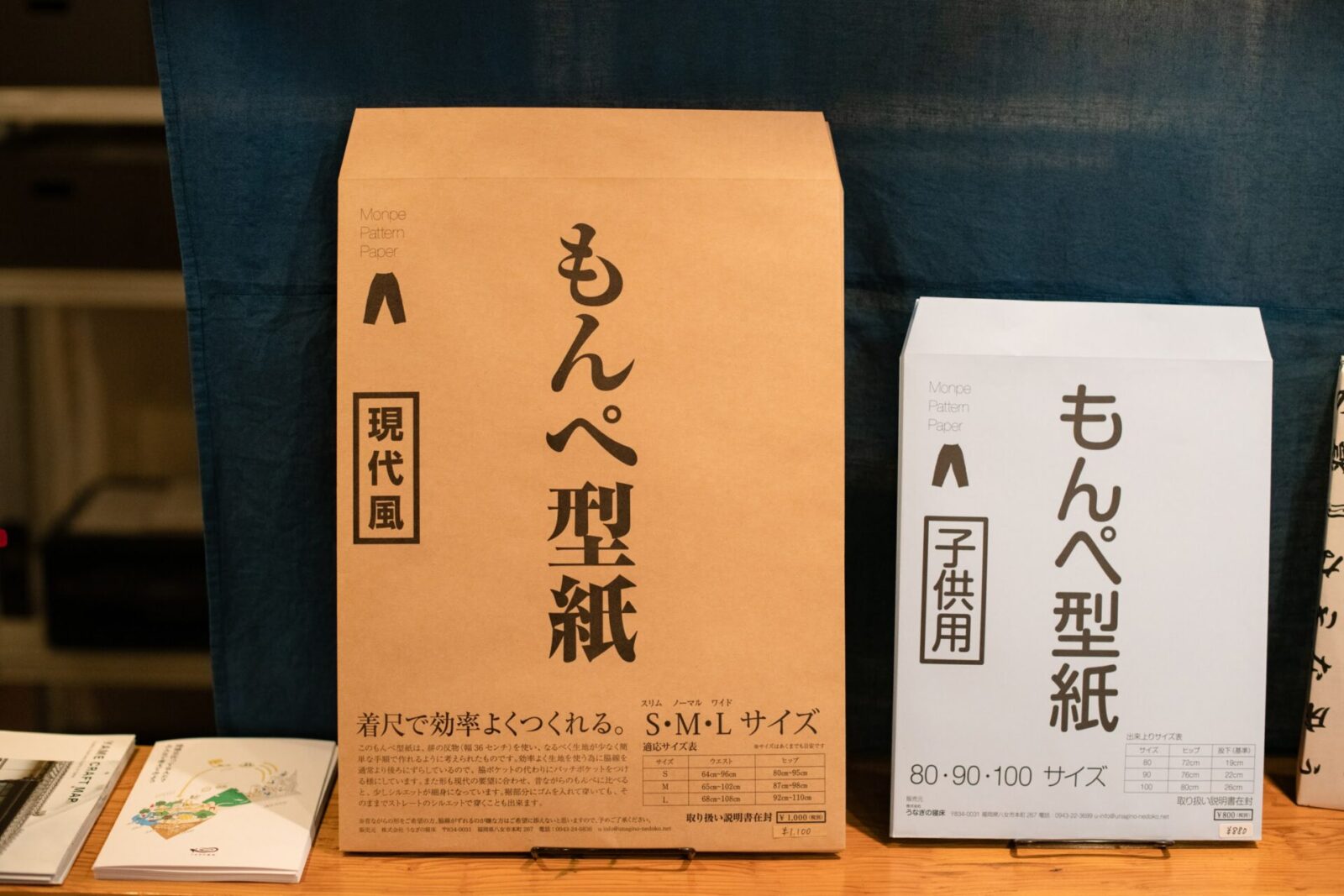

“After we had a child and my wife stopped working at the traditional arts center, I became responsible for continuing the Monpe Exposition. People asked for the monpe sewing patterns so we started selling them first.”

Shiramizu emphasizes the significance of monpe’s history and its functionality.

“Monpe was designated as the standard uniform for women during the war. This was because in case of air raids, it was difficult to run for cover in the kimono.”

“After the war ended, people continued to wear monpe for farm work because they were so comfortable. It is similar how jeans, which used to be work pants for miners in the US, became standard clothes for everyday use. I wanted to make monpe the jeans of Japan.”

Solid color Kurume Kasuri is an “industrial revolution”

From 2014, the Unagi no Nedoko began full-scale sales of the modern MONPE. Their biggest emphasis was on using solid colored fabrics using kasuri fabrics that have a unique texture.

Shiramizu laughs as he says, “Using solid colored fabrics was an industrial revolution for the Kurume Kasuri industry.”

“When I visited the production factories, I learned that the fabric weavers believed that creating fabrics with patterns was what defined the Kurume Kasuri fabric. However, when it comes to choosing clothes for everyday wear, patterns can be too assertive. Solid colors are easier to match with other clothes. I myself wanted a pair of solid colored monpe.”

“Making patterned fabrics also lowers production efficiency and raises costs. However, the comfortable texture of the fabric remains the same, even for solid colors. I wanted people to first give solid colored monpe a try and experience how comfortable they are. After starting with solid colors, we expanded the options to other patterns and strips for a more in-depth experience.”

Even now, their best selling monpe are those with solid and neutral colors such as navy and black.

However, the choices of colorful monpe and various patterns help garner attention of a wide audience, which also helps in the sales of the solid colored monpe.

Today, in addition to Kurume Kasuri, they also sell MONPE using fabrics such as Hyogo’s Baunshuori and Hiroshima’s Bingofushiori fabrics.

MONPE became “the jeans of Japan” as the unique fabrics of various regions in Japan became integrated in the everyday lives of people. Shiramizu hopes that people will “try out different fabrics and compare them.”

We asked if there was a gender, age group, or use that he targeted when producing MONPE. Shiramizu answered that he is “careful not to make any hard-set decisions.”

“I am careful not to make MONPE into a brand.”

“We make solid colored and patterned versions without deciding the target consumer. We spread information in all different ways so it reaches people of different interests, such as those who are interested in traditional craftsmanship, or those who saw us on TV and became interested, or those who simply want to wear comfortable clothes.”

What they consider most important is to include three elements: functionality, cultural significance, and visual satisfaction.

“The most important element is that it is made to be functional. Clothing is a part of life, so comfort is important. If it is comfortable, the product will become known to general consumers through word of mouth.”

“Next is cultural significance. Comparing the history of monpe with jeans helps us create a story that attracts newspapers and TV media. The final visual satisfaction is effective in showing off the attraction of monpe to both consumers and media.”

“A lot of people design based on looks first, but we first focus on functionality, then dig into the cultural aspect, and finally think about how to make it look.”

Like music, textiles are universal

Gyozo Shimogawa, a third generation Kurume Kasuri maker and owner of Shimogawa Orimono says, “We were greatly saved by Unagi no Nedoko.”

“We are very confident in our ability to make textiles, but I was not very good at making clothing out of the finished fabric. I believe we met our ideal business partner.”

Shimogawa shares that when Shiromizu first told him about commercializing MONPE, he was unsure.

“There are ranks in the grade of Kurume Kasuri fabrics, and monpe, which is farming clothes, was made from lower grade fabrics. The weavers who were making monpe went out of business because of the low selling prices. My parents warned me not to make monpe. Honestly, I was very worried about the endeavor.”

“However, Unagi no Nedoko succeeded in creating a completely new image for monpe. We garnered a lot of attention online. Now that I think about it, monpe is something that is easily loved by all, regardless of gender or age.”

Kurume Kasuri is dyed using a thread-wrapping technique before weaving the warp and weft threads.

The Shimogawa Orimono factory uses machines that are over 80 years old, so the threads of the Kasuri are less taut and the weave is looser. The lightness and softness of the fabric becomes similar to that of hand-woven fabric, making it more comfortable to wear.

Many people from overseas visit the Shimogawa Orimono factory for tours and work-study programs. Currently, a woman from Germany who studies fashion design is staying at the factory for her study abroad in Japan.

Shimogawa says that “Textiles are universal, like music.”

“The pattern for kasuri is like a music score. That’s why I hope people from around the world can recreate them.”

“At first, people come because they are interested in Kurume Kasuri. However, as people begin to talk to each other, a moment comes when the interest moves from the “object” to the “person”. The person’s desire turns to: “I want to use the Kurume Kasuri that you make.” This communication is like warp and weft, and it is made through these textiles.”

The Unagi no Nedoko local trading company has created a new scene in our daily lives. MONPE has connected the region, culture, and the lives of people through a product.

MONPE is not a brand, but an everyday attire and work clothes that becomes a part of one’s life. A product that helps bring a moment of comfort into individual lives has the same kindness that we find in “Tea Time”.

(Photo: Yuko Kawashima)

Born in 1990, Nagasaki. Freelance writer. Interviews and writes about book authors and other cultural figures. Recent hobby is to watch capybara videos on the Internet.

Editor and creator of the future through words. Former associate editor of Huffington Post Japan. Became independent after working for a publishing company and overseas news media. Assists in communications for corporates and various projects. Born in Gifu, loves cats.