At DIG THE TEA, we explore moments that melt time, such as moments we spend with tea. We continuously look for ways of “positive escape” in our modern world.

The most simple explanation of “positive escape” may simply be to “rest.”

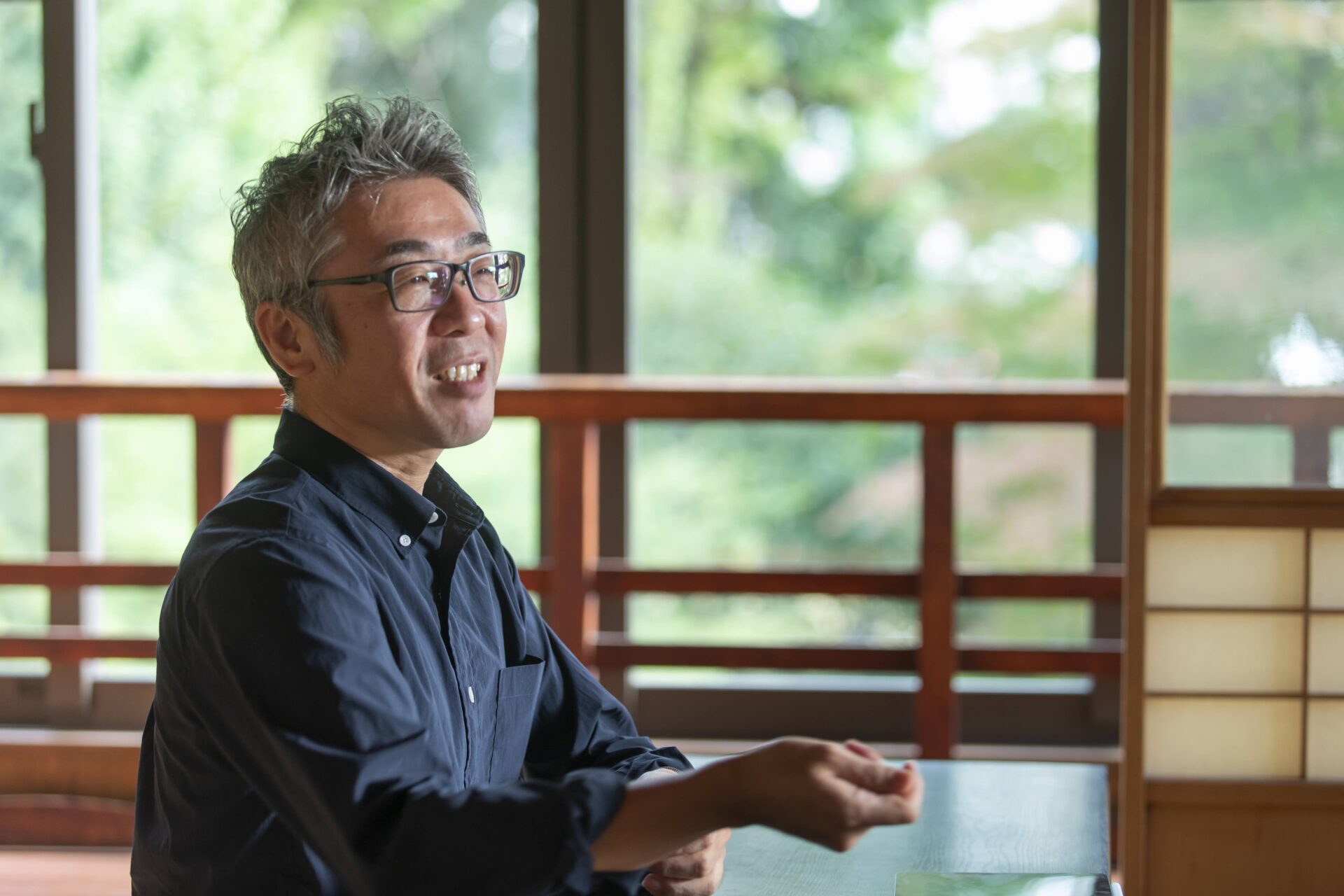

For this article, we interviewed Dr. Naoki Miyano of Kyoto University, who has published books on academic theory, such as Toi no Tatekata (“How to Ask Questions”) (publisher: Chikuma Shinsho) and more. Dr. Miyano is an associate professor at the Center for the Promotion of Interdisciplinary Education and Research at Kyoto University. He is active in creating events and spaces where researchers can sharpen their scholarly spirit through philosophical dialogue.

So what does it mean for us to “rest” in our modern day world?

In what moments is time a form of positive escape?

In the picturesque facilities of Kyoto University, we asked Dr. Miyano about our questions regarding time and rest.

Rethinking “rest” through yardwork

━━ First and foremost, how do you define “rest”?

When you work in the research and the academic world, there is no such thing as absolute rest. We researchers are thinking about our field of study all the time. I am sure artists are the same in that their minds are always actively thinking about their creations. It is not like a job where you have a time card that indicates an obvious start and end time.

━━ Do you mean you have no days off? Isn’t that hard on you in the long run?

Perhaps it is. However, if you look at it from a different perspective, perhaps the job of a researcher is much like we are resting all the time.

The question is, what do researchers consider to be “rest”? I think the definition of rest is to become immersed in something different from the norm. To be immersed means that you become both physically and mentally totally absorbed in something.

For example, an activity I am recently immersing myself in is yard work.

━━ Yard work? Like cutting grass?

Around the parking area of where I live, there is an empty lot that is overgrown with weeds.

As I watched the weeds grow longer, I was waiting for the contractors in charge of maintaining the lot to come and cut the grass, but one day I saw one of my neighbors cutting the grass around his lot and I had a realization.

I realized I don’t have to wait until the contractors come. I could cut the grass myself! As obvious as it seemed, it was a sudden realization and I quickly became hooked after that. Right away, I went and bought my own sickle (a grass cutting tool).

What amazing fun it was to mindlessly cut through the grass!

I enjoy the sound of the grass getting cut and the scents that rise from it. I also enjoy the movement of my body and how I sweat, and the sensation of achievement at the freshly cleaned land that makes our daily environment more pleasant. Cutting grass is full of positive experiences.

When I put the blade of my very well-sharpened sickle to the grass, I hear a very clear “ding” sound. As I sharpen it, I wonder if a Japanese katana sword used to make a similar sound. I ended up buying four or five sickles in total, just to cut grass.

━━ I see what you mean by being totally immersed.

The other day, I wondered if it was wise to keep such a wonderful activity to myself, so I started a club called the “I Love Mowing Club” and put up posters in my apartment complex to advertise it.

Alas, I don’t plan on relying on others and I simply enjoy continuing this activity by myself.

Some people may think that cutting grass is meaningless and not something you immerse yourself into since no matter how much you cut, it all grows back. But for me, the time I spend immersed in cutting is my way of relaxing.

It is a way of escaping from my work and research. Both work and rest are a part of our activities and life.

━━ Do you mean that time spent on research and rest are both essential in life?

Greek philosopher Socrates said “To live is to take care of the soul.” My understanding of these words is that one must be honest with oneself.

We have to be sensitive to our thoughts and sharpen our senses. For me, there is no difference between cutting grass and doing my academic work. They are both activities I take part in for myself, so it is the same.

Time you can can and can’t measure

━━ For you, how do you describe the time that you spend “immersed” in something?

Philosophers from past and present have left a lot of texts on the concept of time. I myself like the way French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941) perceived time.

I believe Bergson described time as having two varieties. One is “objective” time that can be measured evenly by a watch, minute by minute, and the other is a time with a quality that cannot be measured.

━━ Time that can be measured is easy to comprehend, but what qualifies as time that cannot be measured?

It is “qualitative” time.

For example, have you ever been so caught up in something that, to your surprise, the day was over before you knew it? When you are concentrating and your senses are sharpened, people say they enter a kind of “zone.” On the other hand, we all have experiences as a child where it felt like we had too much time and the days felt neverending.

This kind of “qualitative” time is the time of our inner subjective experience, and that is what Bergson described as the true essence of time.

DIG THE TEA’s exploration of time that melts the heart in playful ways can also be described as a philosophical exploration of what “defines time.”

Is “Rest” the opposite of “Work”?

━━ We believe that people today who lead very busy lives need to spend more time in a positive escape.

In regard to your first question, I wondered why you polarized the idea of “rest” and “work.” I don’t think the opposite idea of “work” is “rest.”

So what is the opposite of “work”?

A common idea is that, if work is essentially the time we spend making “a living,” then the opposite of that would be “consumption.” A lot of people use their time off to go shopping.

Then what is the opposite of “rest”? Perhaps it is “existence.”

Taking breaks is something you do while you are working. However, if you define “rest” as “escape from duty,” when you are seriously immersed in something, then “rest” can be something that you have to do and “want” to do at the same time.

Ideally, your job is something you “want” to do, but in that case there really is no difference between work and rest.

Since there is no difference and it is all a part of human life, then the opposite would be a state where there is no life, or essentially, death. In that sense, one could argue that true rest comes when we die.

━━ When you look at the underlying meaning, I can understand why it is important not to simply polarize the two.

It is a habit of the human way of thinking to put things into opposing groups like “rest” and “work.” For example, we think of “friend” and “enemy” or “good” and “evil.” This is an easy way to look at things, but do we really understand it?

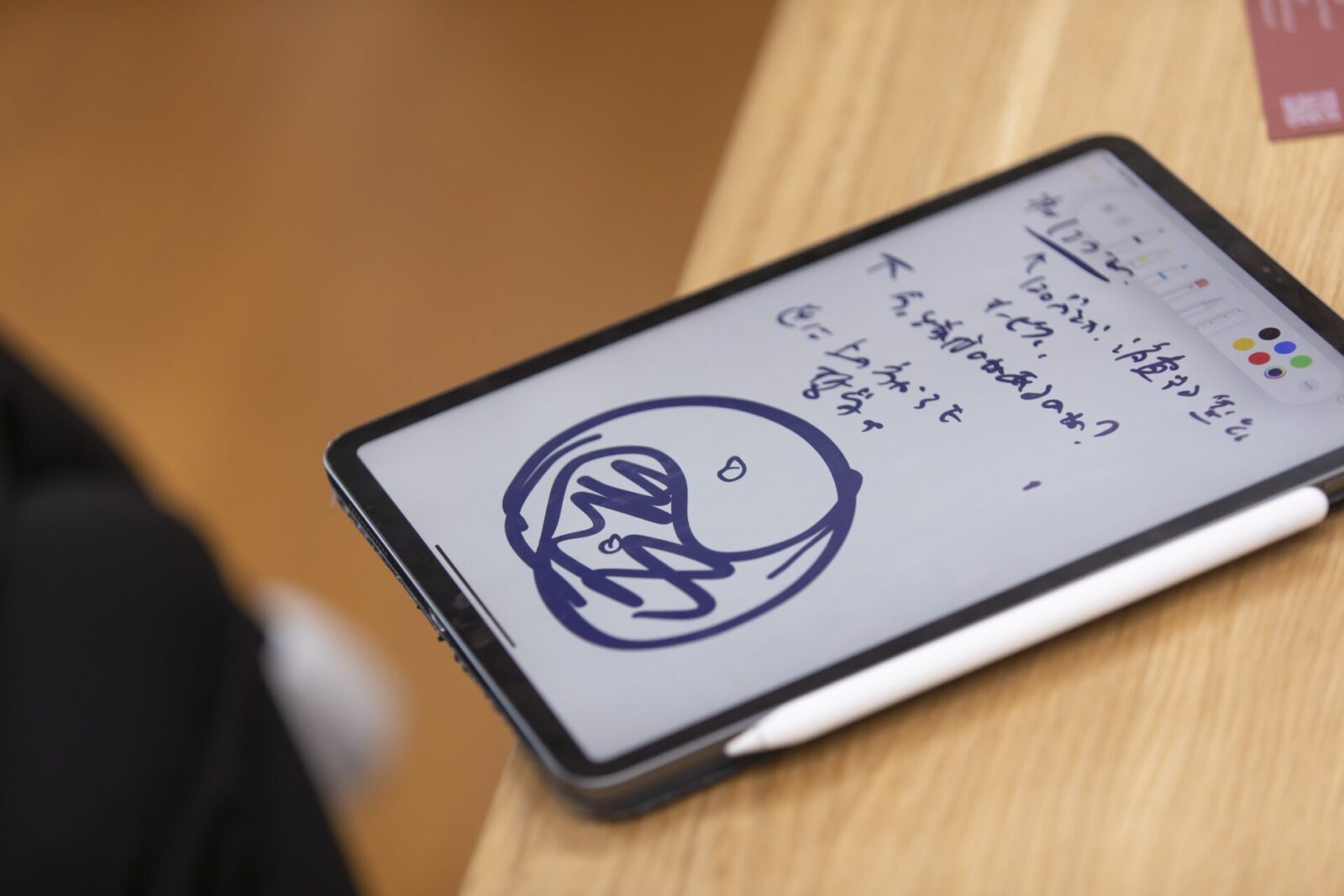

Dōgen (1200-1253), a Zen monk of the Kamakura period (1185-1333) said that “there is truth in uncertainty.” There are things that cannot simply be polarized. I feel the taijitu symbol, which intertwines black and white, accurately portrays our world where things are not simply one way or the other.

“School” comes from “leisure”: the relationship between resting and learning

━━ Earlier you mentioned that the opposite of “rest” is “existence,” as in true rest is essentially like death. Can you tell us more about your understanding of “rest” in the context that it is not the opposite of “work”?

To better understand what defines “rest,” there are some hints in the Latin world for “scholar.”

English words like school, scholar, and scholarship come from the Latin word “schola.” meaning school.

The Latin word “schola” comes from the Greek word “skholē,” which means leisure or boredom. In other words, it was the people who had patrons that paid for their livelihood that had enough leisurely time on their hands to pursue academics.

━━ So the origin of the word school and scholar actually means leisure?

I did some research and found out that the Greek word “skholē” not only means leisure, but it also means “active mental activity.” Active mental activity is another way of saying, looking into oneself.

In other words, there is an aspect in “rest” in which you look inward towards yourself, reflect, and get to know yourself.

━━ What kind of effect does resting and looking into oneself have?

The American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) said:

A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages. Yet he dismisses without notice his thought, because it is his.

The “gleam of light which flashes across his mind” is inside ourselves. The doubts and uncertainties that arise from the inside of our hearts are important. It is better to listen to your inner voices and search for your true self.

For example, I think the philosophers of ancient Greece were able to come up with some universal truths because they had endless conversations with others, and spent endless time in self-reflection and self-doubt. Self reflection does not mean thinking only of yourself, but rather it means losing oneself.

What we need in order to confront the “real” questions

━━ Would you say that academia began in order for us to actively stimulate our minds and search for ideas and questions internally?

In academia, the way we formulate questions is very important.

It is common knowledge in academic practice to formulate hypotheses and then to test them, but what kind of hypothesis should we formulate?

I think that in academia, we approach truth and valuable knowledge by asking questions, questioning them thoroughly, and scrutinizing them even further. If the quality of the question is low, the quality of the research also becomes obsolete.

━━ In what cases are the quality of questions considered low?

We often hear of Nobel prize laureates and those in positions of power say that people should research things that they are interested in. Although I think this advice is meaningful, depending on who takes this advice, they may think, “Okay, I will simply pursue whatever I am interested in.” As a result, they may pursue a very shallow question.

Let me explain by providing an example.

Let’s say that a researcher is interested in turning the current 2 hour 10 minute bullet train ride from Tokyo to Kyoto into a 1 hour trip.

First of all, we must question, is a shorter train ride really that desirable? There may be businessmen who will not welcome the idea of making the round trip ride faster because it gives them more time to work rather than sit on the train.

It is necessary to question why a researcher came up with their question in the first place. To simply believe that going faster is better or being more efficient is better is quite a shallow way of thinking.

Although this is just an imaginary example, you often see researchers pursue these questions that attempt to change an obvious inconvenience into something more convenient. However, I believe it is often the “unseen” question that is important. It is the question of why that question exists.

How to create space for dialogue

━━ What should we do to avoid asking shallow questions?

There is nothing wrong with shallow questions. As long as the person asking the question is aware of that fact. It is necessary to question one’s own interests, and to question and rethink the questions one has raised. I think it is very important for researchers to do this, and as long as this process of reexamination follows, any kind of question is a good one.

The important thing is, as an academic discipline, one must think it through to the end, and then keep thinking some more. What I think nurtures these thinking processes is fundamental dialogue.

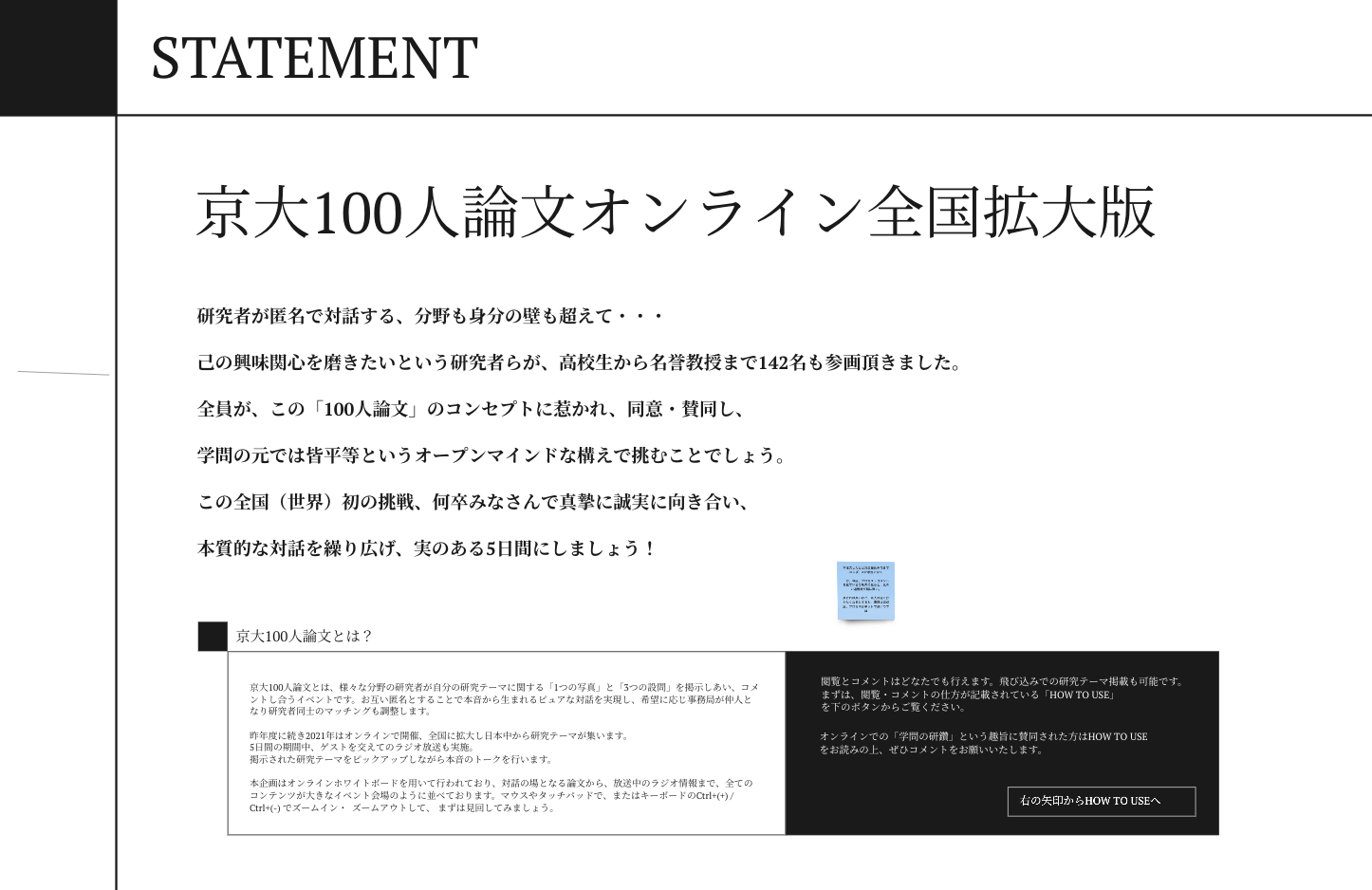

I don’t need to even go as far as mentioning examples of Greek philosophers. In order to get closer to the truth of things, we must have high quality dialogue that helps us raise more questions to think more thoroughly. In order to create such a place for dialogue, we began the Kyoto University 100 Papers project.

━━ What is the Kyoto University 100 Papers project?

In 2021, the Kyoto University 100 Papers was held for the 9th time. Various researchers post one picture and three questions regarding their topic of research, and anonymously comment on each other’s papers online. The last event was very successful and we had 146 posts with over 3 thousand post-it notes.

━━ Which dialogue left an impression on you this year?

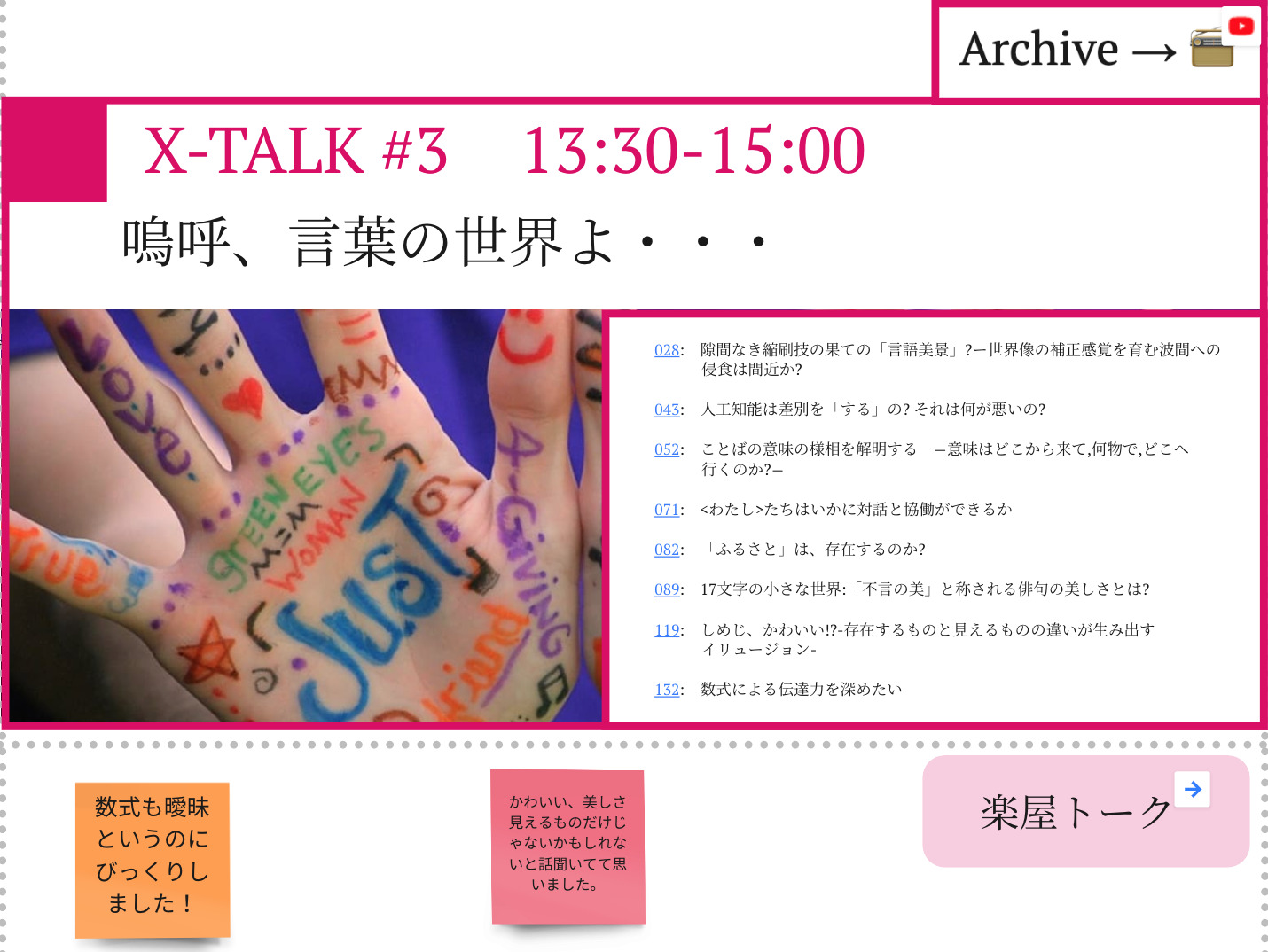

If I were to give one example, the public dialogue called “Aha, the world of words…”, where linguists and AI researchers gathered and talked about the ambiguity of mathematical formulas, was very interesting.

Many people believe there is a perfection to mathematical formulas, but in fact, it only shows relations and there is a lot of ambiguity. If you look at musical scores, even if the same orchestra used the same score, the performance will vary depending on the conductor. This is because the performance is based on the conductor’s interpretation of the score. This is also true with mathematical formulas, as the message will change depending on interpretation.

At the public dialogue, this point expanded into the discussion of “what are words?” At the Kyoto University 100 Papers, we have numerous discussions of such nature.

An academic journal designed for study through dialogue

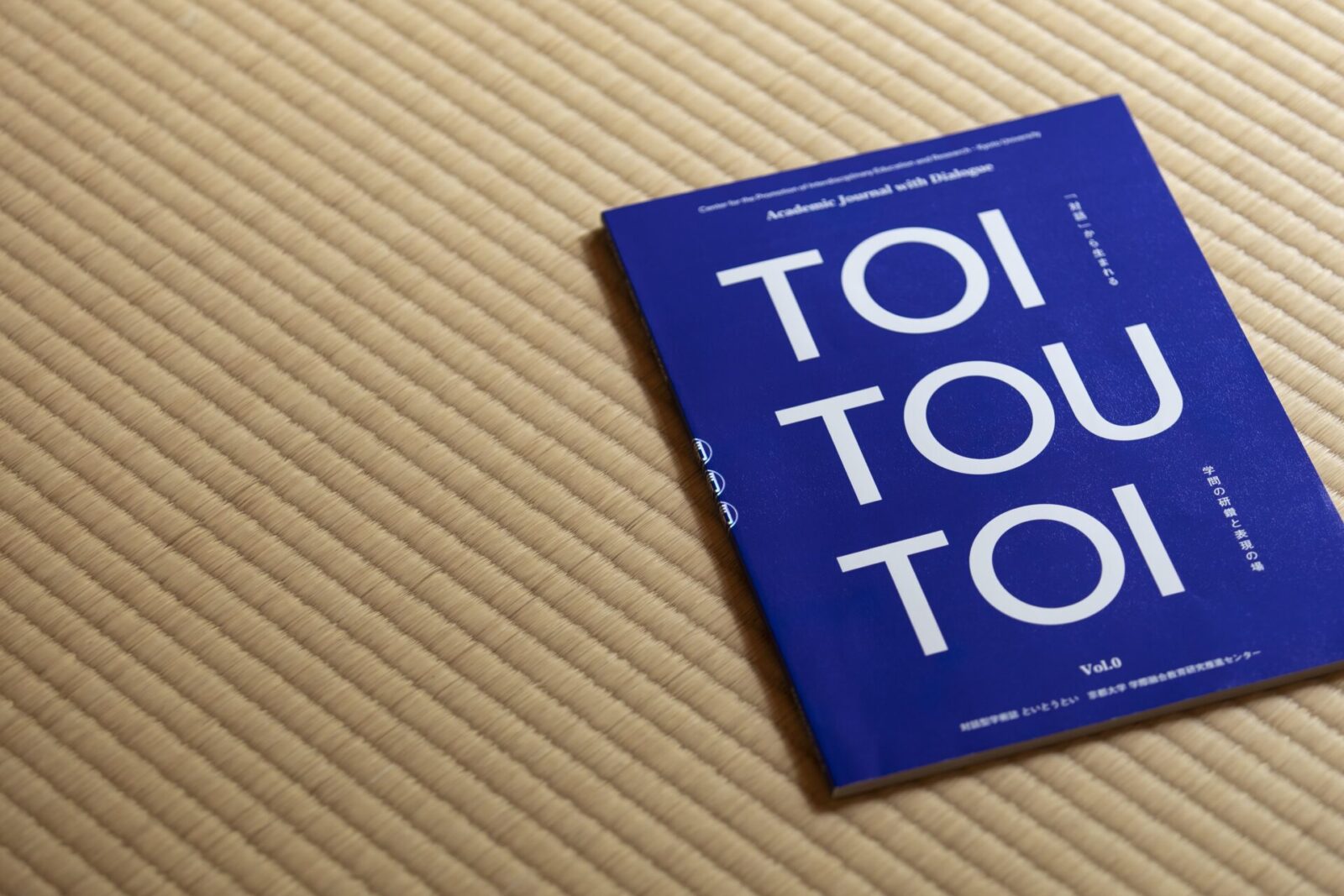

━━ This year, you launched a new academic journal ToiTouToi. What is the idea behind this project?

ToiTouToi, which we published in June of 2021, is unique because it is an academic journal for interactive dialogue.

We focus on increasing the level of interest among researchers by asking “why study such a theme?” Vol. 0 featured eight essays by researchers who are trying to break new ground, as well as dialogue between the authors, editorial board members, and other intellectuals.

━━ What led you to launching this magazine?

There were problems with the current academic world that we wanted to address so we launched this interactive academic journal.

In today’s academic papers, there are formats we follow. There are terms, objectives, and experimental methods, and each field has certain rules and etiquettes. If you follow these rules, you are guaranteed that you will be able to write a “readable paper.”

If you turn this fact around, as long as you follow these rules, you can get a peer review and get your paper published. At that moment, the value of the research itself is no longer questioned.

For example, even Darwin’s theory of evolution was treated as a violent theory back when it was first published. Now, as long as the rules are followed, the judgement of the contents is in a way passed onto future generations. That makes the format become more of a priority.

However, just like there is a light and dark side to all things, there are negative aspects of this practice. I am personally concerned about these negatives.

━━ What exactly are the negatives?

Formalism. The measure of a paper’s merit now is not about the content, but whether the paper is written in a proper format or not, or which journal it was published in.

Formalism has created a sense of significance in adhering to that formality. I believe that we need to strive to question this practice altogether.

How can we create an academic journal for the purpose of refining each other’s thoughts? For ToiTouToi, the editor-in-chief Shinya Yashiro and I put a lot of thought and discussion into this matter.

For example, at ToiTouToi, we questioned words and logic itself as we worked with photographer Go Itami to create content that evokes the senses. I believe we have created an academic journal unlike any other.

Listen to the demon’s whisperings and live from your heart

━━ From cutting grass to academics, the Kyoto University 100 Paper, and your new academic journal, I must say I am very impressed at your endless energy. How do you maintain such passion for so many things?

I am simply curious. I don’t know why I am curious, but I am. That is why I desire to immerse myself in things. I want to stay honest and sensitive to my senses.

I have had many interests, ranging from building my own desk and making my car stereo to mountain biking and gardening. I have also given my all to the 9 years of the Kyoto University 100 Papers project and the ToiTouToi magazine.

I don’t make rational decisions based on assumed outcomes and conclusions. Rather, I know in my mind that these pursuits will bring on many challenges and it would be easier not to pursue them. In fact, every time I give my all to the Kyoto University 100 Papers project, by the end I feel I never want to do it again, but then I do.

This is me listening to my inner demon telling me to do more. There is no other way to explain it.

I believe that our inner mysteries, surprises, and curiosity is the most important thing for academics and I want to nurture that. I want to stay true and honest to the desires in my heart. I want to be the embodiment of the kind of learning that I believe in.

………

“There is no need to polarize the idea of rest and work, on and off.”

Dr. Miyano posed a very straightforward question to us. Although DIG THE TEA explores ways of spending time in positive escape, he made us realize that our ideas have been trapped in the mindset of people living in modern day society.

The reason why we feel overrun by work and information is because we don’t have time to reflect on ourselves. When each of us begin to face our inner questions, learn, and progress, both work and rest become simply a part of human life.

Dr. Miyano said that DIG THE TEA’s mission is a philosophical exploration of what defines time. His words were very encouraging and we hope to continue on this journey of exploring time.

Photo: Yuki Kimura

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Editor / Writer. A freelance editor. Born in Yokohama and based in Kyoto. Associate editor of the free magazine “Hankei 500m” and “Occhan -Obachan”. Interests include food, media and career education programs such as “Internships for Adults”. Hobby is paper cutting.

Editor and creator of the future through words. Former associate editor of Huffington Post Japan. Became independent after working for a publishing company and overseas news media. Assists in communications for corporates and various projects. Born in Gifu, loves cats.