Shikohin is something that we consume that may not have any nutritional value or benefit in sustaining our bodies.

Even though it is not a necessity to sustain life, shikohin is enjoyed in various ways around the world.

Perhaps shikohin is rather a necessary part of what makes us human.

When contemplating shikohin, we must address the question of what is necessary for human life, and by extension, what defines humans as a living being.

For our new series, “To Live, To Relish,” we will explore what shikohin and its experiences means to us in our modern world, and interview leading researchers, anthropologists, historians, and more.

In Part 1 of this interview, “To Treat and to be Treated: How Tanzanians Use Coffee to Maintain Balanced Relationships”, cultural anthropologist Sayaka Ogawa told us about the role shikohin plays in building equal relationships.

The difference between exchanging money and gifts

—— In the first part of this interview, you told us about how casual exchange of shikohin such as 10-yen coffees and cigarettes help create equal relationships. Are there differences in the way gift giving is perceived in Tanzania compared to Japan?

It is very different. When people receive a gift in Japan, they immediately return the favor. Furthermore, Japanese people try to find a gift that is about equal in value to that which was received.

However, I want you to think about something. If the gift you give is returned by something of similar value right away, it is almost the same thing as exchanging something in the market, like handing over bread and getting paid the correct amount of money.

If that is the case, gift giving in Japan is no different from selling bread.

Of course, I am not saying that gift giving in Japan is meaningless because something of a similar value is returned right away. For example, friends will sometimes buy each other gifts that are of similar price. One may think, “Why don’t I just buy something I want from the start?” but we know that is not the point.

The point is that this gift giving is like a ritual that confirms that you and your friend are equals.

Imagine giving your friend a 1,000 yen gift, and getting a 1 million yen ring in return. It won’t feel right, will it? You may begin to wonder what meaning the gift holds, or if your friend is expecting something special from you. You may even think that your friend is showing off by proving that they have more money than you. Either way it is an unsettling situation.

When you give a 3,000 yen present and get something that is about 3,000 yen in return, it feels good because the relationship also feels equal.

On the other hand, the people of Tanzania are different and even if they receive a gift, they may do nothing about it for years.

After spending time living in Tanzania, I have found the sense of urgency to return gifts in Japan to be quite strange. The people of Tanzania will also return favors and gifts someday, but they do not do so until an occasion arises. They may also think that a gift does not have to be returned until that person is in a place of need.

—— It seems the time frame surrounding gift giving is completely different. Why do you think that is?

I wonder the same thing. I think part of it is that Japanese people have a tendency to not want to owe or be owed anything or have their sense of independence feel threatened in some way.

The culture puts a lot of value in independence and self sufficiency, so that may be why Japanese people return gifts and favors right away.

Perhaps it is also because in Japan a lot of value is placed on time, and our society is more centered around selling our time to make a living rather than on labor. This may be another reason such emphasis is put on promptly paying back favors.

—— It’s true that independence and time are highly valued in Japan.

However, the secret to gift giving is always to leave a little bit of debt.

Otherwise, the relationship does not last. If you look back into the origins of gift giving, you will find that gifts and favors were not returned right away, but were returned when the giver of the gift or favor is in need.

David Graeber, an American anthropologist known for his works such as “Bullshit Jobs” and “The Theory of Debt” had an interesting thought about giving in a society without money.

A society without money is not one where people exchange things that they don’t need personally. It is a society where people generously give someone something that they say they want. In return, it is conveyed that when they have something they want, that the favor is returned. A society without money is one that revolves around such promises.

It is not a simple exchange between A and B, and therefore the exchange does not have to happen at the same time.

A safety net that doesn’t rely on corporations or banks

—— For us in Japan, not returning a favor for a long time on purpose sounds like a very new and different concept. Is not returning gifts and favors right away the main characteristic of Tanzanian gift-giving culture?

The difference with Japan isn’t only about not returning gifts and favors right away. The attitude and mindset on the giver’s side is also different.

Although the people of Tanzania help people in need, they do not immediately ask for something in return.

In fact, they actively help as many people and create as many favors as they can.

In other words, it seems that they give to as many people as possible and then just leave it be. It is like they are increasing the number of “impressions” they leave of themselves on others.

—— I am not sure what you mean about giving and just letting it be or increasing the number of “impressions.” Can you elaborate?

In other words, they are creating a situation where there are a lot of people around them that owe them a favor. They no longer even remember who that may be, or how many favors it was, and the people who received it also do not keep track.

However, those who received a favor will remember that person for their help at one time. If there are many people around that have this memory and impression of you, they may help you in return when you are in need one day, and that thought is enough.

—— I see. So for the people in Tanzania, giving favors to people around you is like building a risk hedge.

That’s right. This is why they are willing to give various things and do it so casually.

The diversity in which Tanzanians build their livelihoods are different from the ideas of the Japanese way of doing business. For example, even if a street vendor achieves a certain level of success, it is very rare that they will expand to build a shop or grow into a corporation.

Instead, they may increase their business by opening another street-side business of the same small scale, such as buying a refrigerator and selling soda or a copy machine to start a printing service.

That said, they only have one body and 24 hours in a day.

One may think that if they open a new shop to sell soda or a printing shop, they will hire someone to help them, however, they do not hire others.

Rather than hiring other people, they create exchanges and arrangements with people.

—— What kind of exchanges and arrangements?

For example, they may lend their refrigerator to a young person who does not have a job, and then make an arrangement with them.

Let’s say the average daily sales of soda is 1,000 yen. The owner of the refrigerator will ask that he receive 200 yen a day, and all the remaining profit is for the young person to keep, regardless of how much they earn. In this way, the owner creates an income flow of 200 yen a day, and eventually the refrigerator will belong to that young person.

—— So it is an arrangement between individuals, and depending on how you look at it, it is also a way to help young people who are starting out.

It may seem like the young person is paying for the refrigerator in installments, but that’s not quite the case.

The young person not only gets a refrigerator, they also get a job to earn money and a means to survive.

Because of this, the young person will see the owner of the refrigerator as someone who gave him the opportunity to make a living in this world.

The people of Tanzania use their money in this way, which is different from employing someone to operate their assets to gain capital, and they actively give their assets away to increase the “impressions” they have on other people.

—— So the act of giving and creating impressions on people around them becomes the equivalent of creating their own safety net.

Taxi drivers start off in the same way.

If one were to borrow money from a bank to buy a used taxi, the moment one fails to pay the monthly loan, they may lose their collateral or the car itself. However, when a person with money makes a simple arrangement with a person without money to drive the taxi and pay a predetermined amount per day, and if that person fails to pay one day, they will have to provide an explanation but they will not lose collateral or necessarily lose the car.

After working as a taxi driver for a while, eventually the owner of the car will be satisfied with the amount of money he made and give the taxi to the driver. In this way, the driver will finally become an independent taxi driver.

At the same time, the driver of the taxi will be indebted to the original owner, so even after he becomes independent, the original owner can still call upon the driver if he ever needs a taxi. The investment is made in building a relationship between individuals and this provides peace of mind.

Why relationships are more trustworthy than money

—— It seems that the Tanzanian people are more concerned about the current moment and their current relationships rather than planning ahead and saving for the future. In fact, it seems to me they find their future lies in the relationships that they build in the present.

That is true. The people of Tanzania do not look at time as something that is moving straight into the future. The reason for this is because it is difficult to continue doing the same thing all the time there. One thing can change everything.

The number of people over the age of fourteen who have bank accounts is only about 20 percent of the population in Tanzania. Although they have electronic payment accounts, not much money is kept in them either.

This is not simply because the people are poor, but it is because those who do make money spend it on investing in businesses for other people or they give it to people in need. They save their money through investing in people and relationships.

—— Does this mean that they trust relationships more than banks?

What will happen if the bank collapses or if banknotes lose their value and simply becomes pieces of paper?

In Tanzania, these crises and risks are quite real. Tanzania has a history of drastically changing social systems, from being colonized by Germany and later Britain, to going through a socialist system after gaining independence and then the growth of capitalism in the mid-1980’s.

For the people of Tanzania, the government and banks are not something that they can trust unconditionally.

On the other hand, human relationships are reliable in all situations, whether that be war or jobs being taken over by artificial intelligence in the future. As long as we are alive, human beings will be there for eachother.

For the Tanzanian people, I think that investing their money in helping other people provides a better sense of security than keeping cash or depositing it in a bank.

Tanzania v.s. Japan: finding laughter even in times of hardship

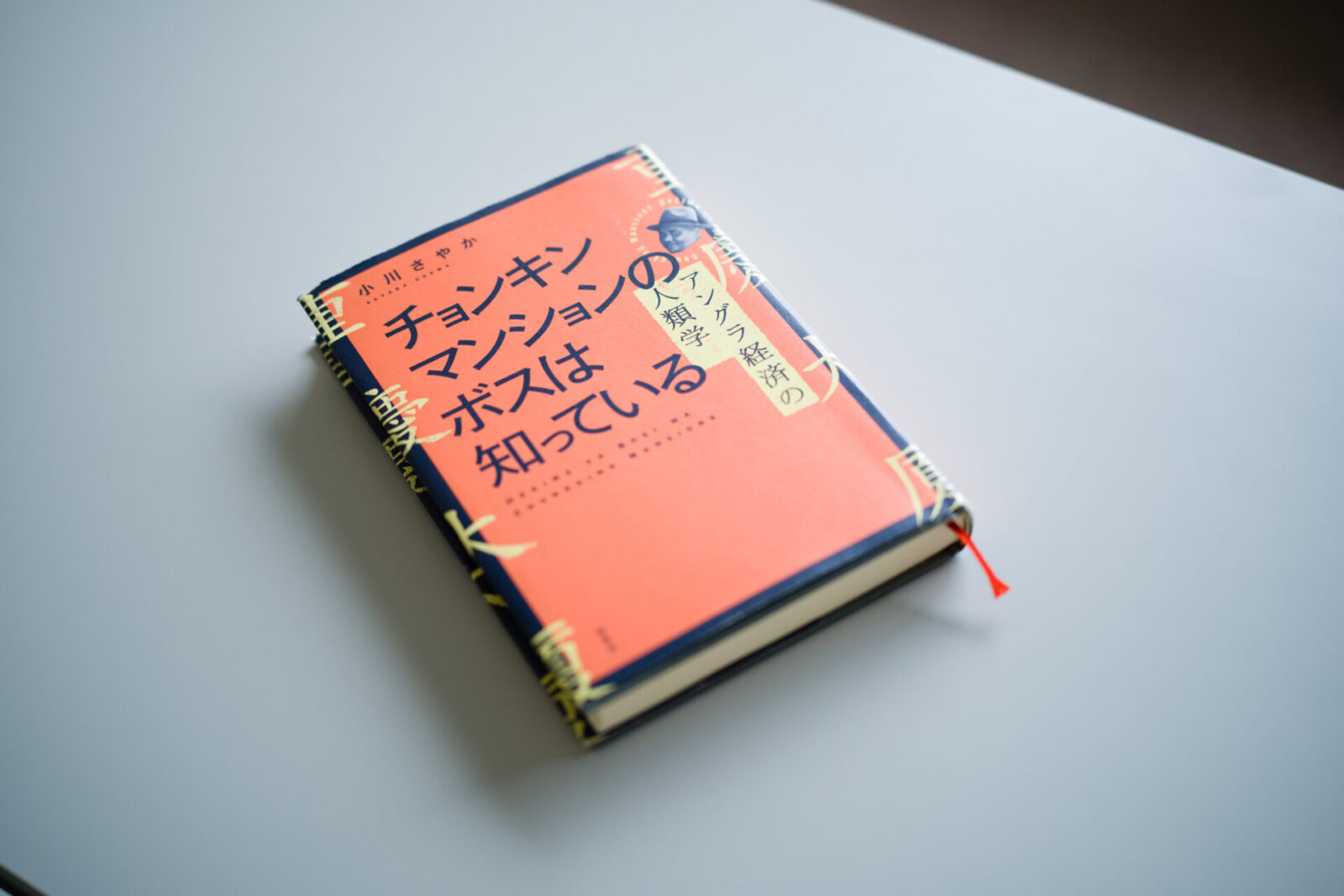

—— There is a key word that appears in your book “Hekima Ya Boshi Wa Chungking Mansions (What the boss of Chungking Mansions knows),” and that is “don’t trust people.”

While they tell me not to trust people, they do not hesitate to let a young stranger stay in their home. While they say ‘don’t trust people,’ they treat each other to meals, lend each other money, and at times they say ‘he/she is trustworthy’ and at times they say ‘I trusted them, but they betrayed me.

page 15 from Hekima Ya Boshi Wa Chungking Mansions

Why do you think the Tanzanian people are able to believe that their act of giving will someday be returned, even if they don’t really trust people?

In Japan, we believe that people are, or should be, consistent in their behavior. However, the Tanzanian view on human nature is different.

They believe that humans are beings that change easily.

When people are hungry, they become grumpy, and when they are feeling satisfied they become generous. In life, there are some sunny days and some rainy days.

Tanzanian people do not believe that they will be repaid for 100 percent of their gifts and favors.

If the person is in a bad mood, maybe the favor won’t be returned and they may betray you or run away. However, if you leave many impressions you are bound to encounter a person in a good mood and somebody is bound to return the favor in some way some day.

—— So one leaves many impressions because of the human tendency to change.

There was one thing that I felt was very different in the way Tanzanians view human nature compared to Japanese.

Tanzanians do not hesitate to laugh at people when they are cornered and in trouble. They may laugh at someone who can no longer pay back his debts, or a man whose wife found out about his extramarital affair. While that person may be on his knees asking for forgiveness, or giving hopeless excuses, the people wholeheartedly laugh at them.

Of course it’s funny. When a person is cornered in that way, their whole spirit and mind are out on public display.

—— So the Tanzanian people see these people in trouble and find it funny and joke about it? In Japan laughing at someone would be considered rude.

In Japan, we think that it is not good to laugh at someone who is in trouble, and I think this is because we think about human nature differently.

In Japan, we think that a person’s true character lies behind the socially responsible character that is built over years of hard work. When we face a difficult situation that is out of our control, our social masks are removed and we show our true nature, but that is something that should not be revealed. We are all afraid of showing our true nature and that is why we cannot laugh about it.

On the other hand, for Tanzanians people expect human beings to change when put in a difficult position.

They look at the acts of getting down on one’s knees and apologizing, or getting angry or upset as a manifestation of that person’s vitality and wisdom to survive any situation.

They do not look at the true nature of someone and the social character that they develop as separate beings. If you look at human nature as something that changes according to the situation at hand, then there is no problem with laughing your heart out at them.

Finding balance between social systems and the act of giving

—— Do you think that people in Tanzania, whose social structures are built on acts of giving, are happier than people in Japan, where many people have a bleak outlook on the future and are expected to live independently?

I don’t know about that. From the viewpoint of Tanzanians, they are envious of countries like Japan that have a solid social system and government.

For example, when people get sick they say that they are envious of how there is no need to find a doctor or taxi driver from among your friends for help, and that everything is covered by insurance in Japan.

It is not because the Tanzanians are more happy that their social structures have developed in the way they have.

Of course, from our viewpoint it is easy to be envious of what we find nice about their society. I myself sometimes worry about being alone when I face some hardship in the future. In that sense, maybe Tanzanians do not experience that kind of loneliness.

At the same time, living in a society where human relations are built on casual giving can also be cumbersome.

Even though you may receive some favors, you are also often asked for them. Of course, there are moments when you tire of someone always asking you to lend them money.

—— That does sound troublesome. On the other hand, I think there are ideas we can learn and borrow from them.

That’s right. Rather than trying to create one system to replace capitalism or modern social welfare institutions, I think it is better to have a variety of social systems. I believe that will make human beings more resilient.

If asked if the world can function with just acts of giving and exchanges, that is not the case.

Problems such as expensive treatment for intractable diseases is not something that can be resolved by a small community of people, so we need to continue to maintain and expand some of these larger social welfare systems.

At the same time, just because we have welfare systems, it does not mean that we do not need to practice the custom of giving. No matter how good one system is, other systems have advantages in other areas.

For example, even though we now have the choice to shop on Amazon, it does not mean that we no longer need physical shops. It is nice to talk to people at real shops, and it is also convenient to have things delivered to your home with just one click. Having multiple options is always good.

In that sense, I think that it would be good if we started to take up the practice of casual giving. In fact, I think it would be even better to give casual gifts to people we don’t like.

—— Small scale casual giving seems like something we could easily try. Why do you think it’s better to give to people we don’t like?

Gift giving is not only about strengthening existing relationships, such as giving a gift to a loved one.

It is also a tool to win over strangers or to get people you may be in conflict with on your side.

—— I see. Giving is a way to change human relations.

It is my belief that human beings don’t have to really understand each other.

I think it is enough if we can accept that there are a lot of different people in this world and coexist without causing major wars or big disputes.

We don’t have to accept, include or understand everything about everyone. I think it is a good practice to occasionally give casual gifts to maintain relationships just enough to allow for us to coexist.

—— So you are saying that gift giving is a tool that helps various people coexist.

Actually, it is said the tradition of gift giving is deteriorating in Japan, but this is not the case. In fact, getting gifts for oneself and for close friends and family is increasing. Donations and volunteering have also shown little decrease.

What is decreasing is obligatory gift giving, which was always something people were unenthusiastic about. Gifts such as year-end gifts, mid-year gifts, and these traditional gift giving customs are on the decline.

However, there was a reason why people used to practice obligatory gift giving, even reluctantly. Without these customs, there are certain relationships that quickly get lost, such as ties with neighbors.

Even if you do it as an obligation, by giving the gift you are increasing the chance of a neighbor coming to check on you during a natural disaster or when you become elderly living alone. It is always going to be cumbersome of course, but it is meaningful.

—— If you think about it that way, obligatory giving in Japan is similar to the gift giving customs in Tanzania, since these cumbersome customs led to forming safety nets in the long run.

For people who are struggling to find happiness in Japan right now, I think we can learn from Tanzanian values and learn to hold onto various options.

I think it would be nice if the custom of obligatory giving in Japan became more enjoyable by making it more casual, with less social pressure. There must be new ways of taking part in the act of gift giving, such as using IT and new technologies, that better suit the modern world. Gifts don’t always have to be an assortment of luxurious goods.

In that sense, shikohin is perfect for casual gift giving.

If we can feel good about treating someone to coffee, and also feel good about being treated once in a while, we can build more equal relationships that transcend differences in gender, age, occupation and social status. Wouldn’t it be nice to live in such a world of casual give and take?

Read Part 1: To Treat and to be Treated: How Tanzanians Use Coffee to Maintain Balanced Relationships

Photo: Saki Irimajiri

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Editor / Writer. A freelance editor. Born in Yokohama and based in Kyoto. Associate editor of the free magazine “Hankei 500m” and “Occhan -Obachan”. Interests include food, media and career education programs such as “Internships for Adults”. Hobby is paper cutting.

Editor and creator of the future through words. Former associate editor of Huffington Post Japan. Became independent after working for a publishing company and overseas news media. Assists in communications for corporates and various projects. Born in Gifu, loves cats.