“The flowing river never stops and yet the water never stays the same.”

Gouranga Charan Pradhan is a postdoctoral fellow researcher at the Research Center for World Buddhist Cultures of Ryukoku University.

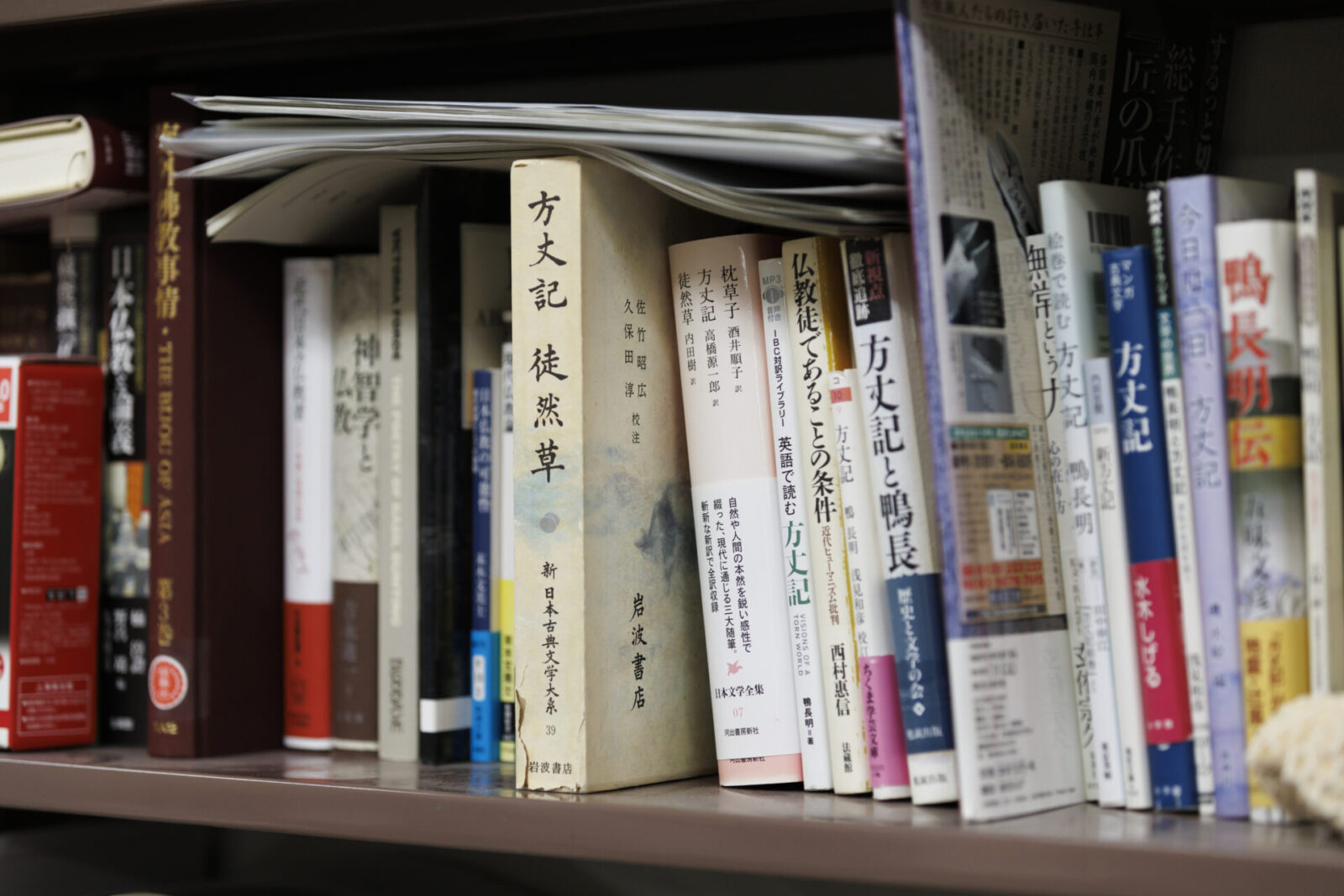

Gouranga first encountered Kamo no Chōmei’s Hōjōki during his masters program at the University of Delhi. He now studies the universality of Hōjōki, which has been translated into nearly 50 languages.

Kamo no Chōmei wrote Hōjōki in his later years after he left his life in the capital of Japan and settled in a hermitage in the mountains where he contemplated the fragility and transience of the world. Although the piece was written 800 years ago in the Kamakura period (1185-1333), the literary piece has garnered attention every time there is a natural disaster or calamity in our world.

Gouranga says that Kamo no Chōmei’s views provide us with hints on how to live in our current and uncertain age of global capitalism, how to face our inner desires and how to survive in this modern world.

Hōjōki emphasizes finding solace and we will explore what the piece means for modern shikohin experiences.

For our series, “To Live, To Relish,” we will explore what shikohin and its experiences mean to us in our modern world, and interview leading researchers, anthropologists, historians, and more.

Shikohin is something that we consume that may not have any nutritional value or benefit in sustaining our bodies.

Even though it is not a necessity to sustain life, shikohin is enjoyed in various ways around the world.

Perhaps shikohin is rather a necessary part of what makes us human.

Are we being driven by material things?

── You are from India and you study Japanese and world literature. You said that you believe that Kamo no Chōmei’s Hōjōki (dated 1212, Kamakura Period) can provide us with hints and be a model on how we should live in the modern world.

Hōjōki is largely divided into two parts, the first half and the second half.

The first half describes in great detail the disasters that struck the capital of Japan. In the second half it describes Kamo no Chōmei’s life after he left the capital and lived a life of Buddhist practices, art and being in nature.

Kamo no Chōmei was born as the second son of Kamo no Nagatsugu, a priest of Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto. Because his father passed away when he was still young, he was unable to succeed his father as the head priest as he had initially hoped.

Nevertheless, he was a talented poet and biwa (Japanese flute) player which led him to develop a friendship with the Emperor Go-Toba and other distinguished poets. However, he struggled in building relationships to further his career in the capital so at the age of 50 he chose to become a monk and live a life of seclusion.

In other words, Kamo no Chōmei was born into an elite family, but after various trials and tribulations he left the richest capital of Japan and began viewing the capital life more objectively from a distance.

As he recited Buddhist prayers and immersed himself in nature, he also pursued arts such as waka (poetry) and biwa (music) and spent his days in self-reflection. While living a simple but free life, he contemplated what true happiness meant in life.

── Hōjōki has always been read after large earthquakes and other natural disasters. What kind of message do you think it holds for today’s society?

Kamo no Chōmei lived a simple life in a small hermitage where he enjoyed taking walks, writing poetry, playing his instrument and love for nature while pursuing Buddhist teachings.

I believe he pondered how to find balance between his simple life and his inner desires while embracing his ideals.

I believe we share this same question as we live our lives in our modern world.

In our modern world, we enjoy a very convenient life thanks to the development of technology and science.

Of course, such advancements themselves are not a bad thing in and of itself. The problem comes from our excessive pursuit of efficiency and productivity.

For example, smartphones have become an indispensable tool for our everyday lives. Realistically, it would be difficult to return to a life without them. However, is it really necessary for us to be forming lines from early in the morning to buy the newest smartphone model that goes on sale?

I feel that we have reached a point where we are being driven by material things more than we are pursuing them.

── What do you mean by being driven by material things?

In the world of market economics, there is no end to the cycle of making and selling goods. We find ourselves being on a schedule controlled by a clock and we are pressed for time by the minute.

What a person values in life is different with each individual so of course there are people who have no qualms with such daily lives.

However, I think that Hōjōki and the lifestyle that Kamo no Chōmei chose to live can provide us with hints on how to better balance our insatiable desires with lifestyles that are more sustainable for us to lead.

This is not only true for our individual everyday lives, but also true for global issues such as climate change and other environmental problems.

── How do you think it can help us resolve global environmental issues?

There is a term “anti-growth” which is the antithesis to consumer society.

Anti-growth does not entail the act of doing nothing in a negative and passive sense. It is about thinking about the limits of growth and finding a balance between production and consumption. It is to think about not only our own lives, but how we should live with others in society as a whole. It is also about thinking of ways to make better changes in the way we live.

Hōjōki can be interpreted as a guide to how we can live as an individual in a market-centered world of global capitalism.

If economic growth and the human population continues to rise at the current rate, we will deplete all the earth’s resources.

So we must make changes.

I believe that Hōjōki holds many clues as to how we can live our lives in such times.

Kamo no Chōmei’s sustainable lifestyle

── As much as I admire Kamo no Chōmei’s way of life, it is difficult to free oneself from greed and desires. In our lives we find ourselves thinking about how to improve our lives by getting promotions, making more money or working more efficiently. Unknowingly we are always pursuing ways to improve time and cost efficiencies.

For those of us who are living in the market economy, we are constantly caught up in material things and we have come to believe that this is normal.

However, if you look around the world in other countries you will find that this is not true in all lifestyles.

For example, in my hometown of Odisha in southeast India, time flows very slowly.

Everyone works as farmers so the amount of work they do varies with the season. When there is not much to do, it is okay for them to do nothing. Sometimes they go out to explore the mountains, but it is not for any particular purpose.

We try to find purpose or achieve results in everything that we do. However, the people of Odisha simply go to the mountains without purpose. If something interesting happens it pleases them, but if not they simply look up towards the heavens. That is all.

From my understanding, the lifestyle that Kamo no Chōmei lived in his later years and the lifestyle of those living in the country of my hometown share some similarities.

Perhaps our future lies in such ways.

In order to live more sustainable lives, I think that aiming for such lifestyles may be necessary.

── You say that there are hints to sustainable living in how Kamo no Chōmei spent his later years. Perhaps it would be good to reread Hōjōki from that perspective.

Kamo no Chōmei chose to leave his life in the capital and live a secluded life after experiencing various disasters, relocations of the capital and other experiences of capital life.

There is no limit to human desires.

Kamo no Chōmei describes this as “worldly attachments.”

He also says that desire does not wish to be satisfied. If so, rather than aiming to satisfy desire, it may be necessary to let go of desire instead.

Making time for yourself that is free of purpose or results

── How would you describe Kamo no Chōmei’s way of life in detail?

I think that Kamo no Chōmei valued physical activity. I believe that he practiced self healing through his body.

He walked in the mountains and picked nuts and berries. When the weather was nice he climbed mountains and once in a while he would travel far distances to visit shrines or the grave of Sarumaru no Dayū, one of 36 renowned poets and personal friend of Kamo no Chōmei.

It is written that he would break off a flowering tree branch and bring it home with him on his way home from these excursions. I believe this is a kind of shikohin experience that uses the physical body.

── You mentioned that Kamo no Chōmei used to play his biwa (Japanese flute) along with the sounds of wind and water.

That’s right. He did not play to entertain others, he played for his own enjoyment and comfort, even if he was not very good at it.

I think that enjoying something without purpose or expectation of results can be a very comforting act.

Perhaps these actions are not valued in our world that expects results and achievements. It may be hard to imagine when we live in a world where we are expected to go to cram schools, get into a top school and work at a good company to get promoted and get ahead in life to become an elite member of society.

But in the end, our lives will all come to an end someday.

Perhaps when we become faced with the limits of efficiency and productivity, the value of choosing not to do anything and being free will be reexamined and valued once again.

We can take it easy.

I think that maybe the time has come to change the way we approach our life and values.

── Perhaps the key is to reclaim time on our own terms and use our time to enjoy ourselves, as Kamo no Chōmei did when he let go of desires and distanced himself from material objects.

I think that is a necessary part of getting to know yourself.

We think we know ourselves, but that is not always the case.

Perhaps using our bodies and minds to really contemplate matters is a way for us to confront our surroundings, environment and technological advancements.

I think right now, it is vital for us to have the time to think about the difficult issues we face.

Ultimately, I believe this will lead to release and solace of our minds. In Hōjōki this is described as “indulgence of our own passions.”

Questions that humans face with the rise of generative AI

── Earlier you mentioned that advances in technology are not bad in and of itself, but do you think there will be a time when the human mind will not be able to keep up with the speed of progress, such as in the case of generative AI?

The pace of technological advances is indeed incredibly fast today. Before we know it an evolution in technology has come and gone and another one takes its place.

I use ChatGPT myself. It is so convenient that it makes sense to utilize it.

Technology itself is but a single phenomenon. There is nothing wrong with technological advancements from happening. The fact that they help make our lives more convenient in itself is a good thing.

The problem arises in how we choose to perceive the technology and how we use it.

After all, it is impossible for all of us to master all technologies.

I think we are living in an age where human individualism will be questioned.

To put it in other words, it is important to think about how we can prevent technology from affecting us in an adverse manner. Ultimately it will be humans who will create and receive bad influences and act maliciously. Again, it is not the technology that is to blame.

── So we must individually decide how we want to live. Do you have any insight that will help people?

I think we must all individually reevaluate and be conscious of the changes we must make in our lives.

Increasing productivity is not necessarily a good thing.

For example, if looking at environmental protection on a global level some people may think we must destroy forests to open up land to build wind power plants.

However, there is also the option of reducing the amount of electricity we use in the first place.

In order to maintain this kind of perception, I believe it is important to be able to make comparisons.

One thing that American writer and naturalist Henry D. Thoreau and Kamo no Chōmei had in common was that they were both born in the city and later left to live in natural and secluded places.

If they only had the experience of living in the city or living in the countryside, they may not have been able to recognize certain things.

I myself am able to make comparisons between the life of rural India and Japan.

Because I am away from India and researching literary works in Japan, I am able to perceive Indian philosophy from a different angle. That is what makes things so interesting. There are connections that I realized only after studying in Japan.

If I had stayed in India my whole life I believe there would have been a lot of aspects of Indian philosophy that I would not have realized.

In today’s world it is important to attain your own perspective away from the city and have your own axis to make comparisons, just as Kamo no Chōmei did.

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Reporter for Business Insider Japan. Born in Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo. Taught world history as a high school teacher, worked for Huffngton Post Japan and BuzzFeed Japan before assuming current position. Interests incude economics, history, and culture. Covers a wide range of topics from VTuber to Rakugo and is interested in food culture from around the world.

Editor / Writer. A freelance editor. Born in Yokohama and based in Kyoto. Associate editor of the free magazine “Hankei 500m” and “Occhan -Obachan”. Interests include food, media and career education programs such as “Internships for Adults”. Hobby is paper cutting.

Editor and creator of the future through words. Former associate editor of Huffington Post Japan. Became independent after working for a publishing company and overseas news media. Assists in communications for corporates and various projects. Born in Gifu, loves cats.