Japanese cultural products ranging from video games, anime and manga to fashions and foods enjoy immense popularity around the world. Among them are shikohin— the Japanese word for pleasure-oriented, non-essential goods, such as Japanese tea and sake.

What is it that makes inessentials from Japan feel so essential to modern life?

One concept that sheds light on the question is that of a “New Japonism.”

In the late 19th century, a wave of fascination with Japanese art and design swept Europe and America. It was known as Japonism, and it had a profound influence on Western artists and aesthetics. Today, we’re witnessing a revival of that fascination— a “New Japonism”— in the form of global interest in Japan’s traditional and pop-cultural exports.

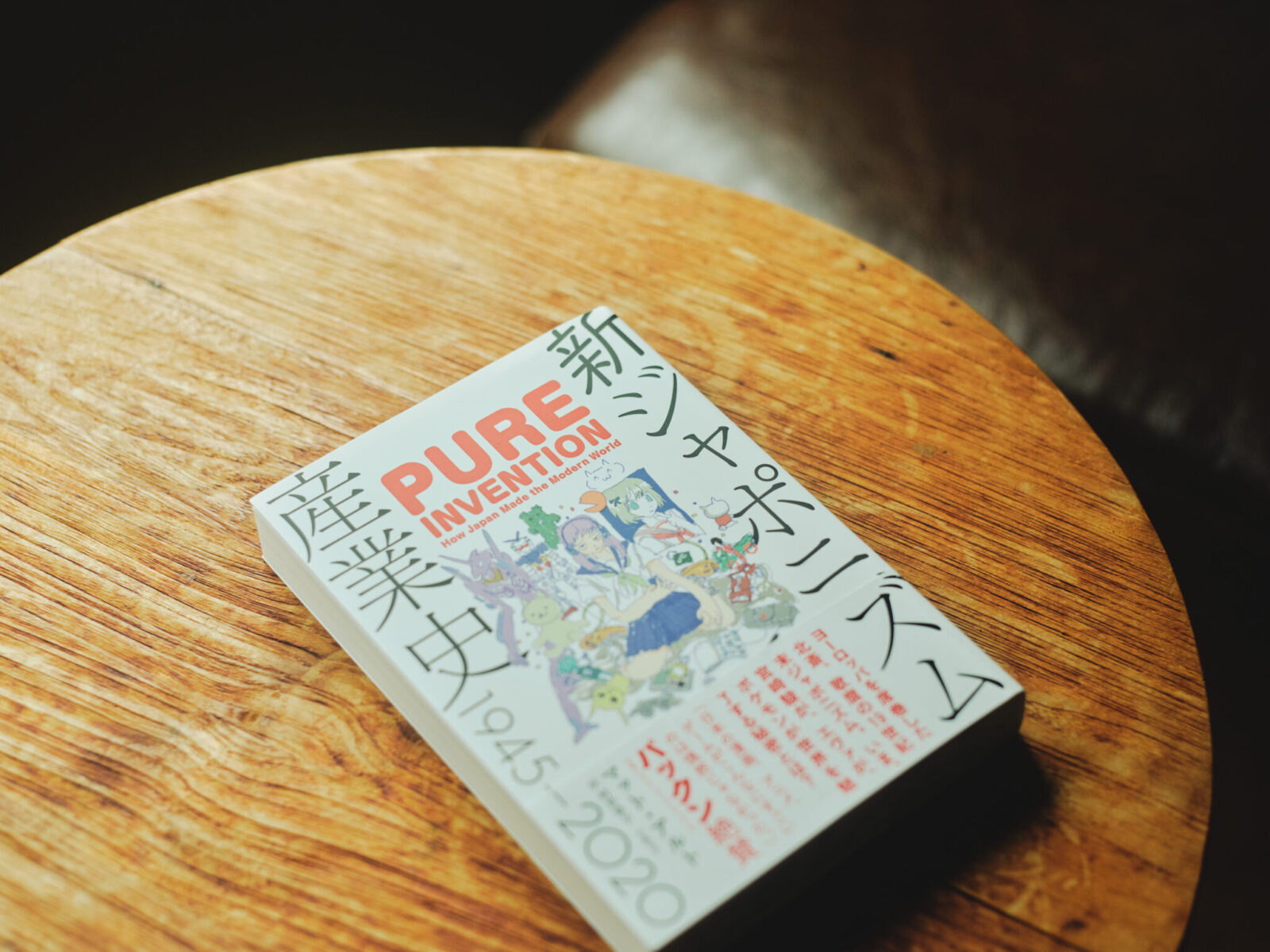

Matt Alt, a Japanese pop culture expert and author of Pure Invention: How Japan Made the Modern World (Nikkei BP, 2021), describes Japan’s rise global success through “fantasy delivery devices.” One of his key definitions of these products is that they are inessential, meaning they are a form of shikohin.

For this article, we interviewed Matt Alt to explore this “New Japonism”. From anime and manga to green tea and cocktails, we explore the reasons why Japanese culture and products are so popular across the globe.

19th century Japonism that influenced even the Tiffany brand

—— How would you describe the concept of New Japonism?

If you want to talk about New Japonism, first you need to look at its historical predecessor, Japonism.

In 1853, the surprise arrival of U.S. Commodore Perry’s fleet arrived in Japanese waters, ending the nation’s nearly two hundred years of isolation. As Japan opened its borders, Japanese products, mainly art and handicrafts, began flowing into Europe and the United States.

Ukiyo-e woodblock prints proved particularly popular. They were utterly unlike Western art, with vivid colors, featuring unconventional subjects, and arranged in unique perspectives. This captivated Western artists and designers. As interest in Japanese culture boomed among tastemakers, a cultural movement in the West boomed, and elements of Japanese aesthetics came to be incorporated in everything from fine art to industrial design and everyday products.

This fad for things Japanese came to be called “Japonism” in Europe and the “Japan boom” in America. Its influence was so strong that it transformed the meaning of sophistication. For instance, Tiffany & Co. rose in prominence through their incorporation of Japanese design elements into their products.

—— The Tiffany & Co.?

That’s right. Tiffany & Co. was founded in New York in 1837, but it was originally a stationery and “fancy goods” emporium.

The founder and his son loved Japanese crafts and Ukiyo-e prints by artists like Katsushika Hokusai. They began directing their designers to make cutlery and tableware that incorporated Japanese elements—at one point declaring their intention to create pieces that felt even “more Japanese than the Japanese.” This creative shift helped redefine Tiffany & Co., transforming it from a modest boutique into a trendy high-end luxury brand.

In other words, Japanese design played a crucial role in shaping the identity and prestige of the now-iconic Tiffany’s brand.

—— So the original Japonism movement was the boom in Japanese cultural influence in the West at the end of the 19th century.

Absolutely. But Japonism began to fade by the mid-20th century, largely due to the onset of World War II. As Japan became an enemy, the Allied nations—led by the United States—actively distanced themselves from Japanese culture and aesthetics, effectively suppressing the popularity of Japonism.

But less than two decades after the war, a new wave of interest in Japan began to emerge in the United States. The first to pick up on it were social dropouts known as beatniks, who saw Far-Eastern philosophy as a kind of antidote to “square” American consumer culture.

Then, in the 1960s, anti-war sentiment surged across America. Out of this movement arose the hippies, who rejected mainstream societal values and championed peace and equality. Both beatniks and hippies took inspiration from Buddhist teachings—particularly the concept of Zen—which they saw as a spiritual counterpoint to capitalist, materialist society.

Some also took note of student protests happening in Japan, footage of which was widely broadcast in America at the time, and adopted elements of their unique protest style – specifically a “Japanese snake dance” that demonstrators used when they marched, linking arms to make it difficult to catch them. That might be the first youth trend to arrive in America after World War II, and marked the start of a postwar “Japan boom” in the United States.

The rise of New Japonism in the 21st century through games and anime

—— Did that boom eventually die out as well?

It did. By 1968, Japan had risen to become the second-largest economy in the world, right behind the United States. As Japan’s economic power and global influence grew, so did trade tensions, especially in the late 1970s and 1980s. This led to a surge in anti-Japanese sentiment among American adults.

Interestingly, however, this sentiment wasn’t shared by the younger Americans. They didn’t associate Japan with economic rivalry, but with excitement and wonder.

I was one of those kids. I was born in 1973, and for as long as I can remember, I’ve been fascinated by Japan. That fascination came directly from the toys and games pouring in from Japan during my childhood.

One of the biggest moments was the release of the Family Computer, known in the U.S. as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), in 1985.

By the time I was born, Japanese-made products were already a common part of everyday American life. I grew up surrounded by items like cars, watches, cameras, and VCRs that were made in Japan. And toys, of course. But the arrival of the NES marked a completely different level of cultural impact.

For instance, while our VCRs may have been manufactured in Japan, the content we watched on them was almost entirely American TV shows and Hollywood movies. It was distinctly Western.

But the NES was different. It also compelled you to play Japanese software. Every game we played was created in Japan, infused with unique worlds, characters, and a distinctly Japanese sense of design and storytelling.

Around this same time, other forms of Japanese pop culture began to make their way into American homes. Characters like Sanrio’s Hello Kitty, toys such as The Transformers, and monster films like Godzilla led the way. A few years later, the Super Sentai series (adapted in the U.S. as Power Rangers), and anime like Dragon Ball Z began airing on American television.

This influx of Japanese media captured the imagination of a generation and sparked a new Japan boom among younger audiences.

—— This new movement is what we now understand as New Japonism?

You got it. Back in the 1970s and 80s, if you asked young Americans what they thought was the coolest place in the world, most would have answered with the U.S. or some major American city.

But by the 1990s, that perception began to shift. More and more young people, influenced by Japanese pop culture, design, and products, started to see Japan as the coolest place on earth.

A blend of the “known” and “unknown” sparks the movement

—— Why do you think Japanese content captivated the younger generation in the US so much?

I think there are many factors behind Japan’s global appeal, but the most important is its ability to strike a perfect balance between the “familiar” and the “unfamiliar.”

What I mean by this is that it’s often said that people seek out new things, but that’s not entirely true. When something is totally unfamiliar, it can feel too foreign or confusing to engage with. On the other hand, things that are too familiar can’t spark curiosity or excitement.

You need just the right blend of “familiar” and “unfamiliar” to spark a new trend, and Japanese products often offer a perfect combination of the two. We understand what they are, but they obviously emerged from a worldview different from our own.

A great example is the Tamagotchi craze. It exploded in Japan in 1996, then became a huge sensation in the U.S. a year later in 1997.

At a glance, a Tamagotchi looked like a small calculator or something. It had a tiny LCD screen and buttons. It looked like a gadget Americans were already familiar with. But inside that tiny screen lived a creature, one you had take care of — and that was a completely new and unexpected concept at the time.

Karaoke is another good example. Americans were already familiar with the components: microphones, tape decks, and speakers. But the idea of putting them together, and removing the vocals from a song so you could play the role of a star, was a fresh, unfamiliar experience. That mix of the familiar and fresh helped karaoke, born in Japan, become a popular pastime all over the world.

—— So the strength in Japanese products was that it had a combination of familiarity while offering a completely new experience for many people.

The same principle explains why Japanese games, anime, and manga became so popular around the world. With these products the “unfamiliar” element often can be found in the values and worldviews embedded in the stories.

The NES played a key role in launching Japan’s global gaming success, but video games certainly existed before that. America invented video games! And America also had a thriving cartoon and comic book culture, dating back to the 1930s.

What made Japanese games and also anime, and manga stand out was how they presented completely different perspectives, values, and stories—ones that felt unfamiliar and intriguing to Western audiences.

Take the Mobile Suit Gundam series, for example. It was introduced to American audiences in the late 1990s through cable television. “Gundam Wing” was a huge hit, and paved the way for both earlier and later incarnations of the franchise.

—— What was it about Gundam that was “unknown” to the American audience?

For Westerners, the freshest element of the Gundam series was its portrayal of the heroes, who were often reluctant protagonists. Amuro Ray, the star of the original series, is a super soldier who has no desire to fight. This was a stark contrast to the typical American cartoon hero—often depicted as macho, confident, and eager for battle.

A reluctant, emotionally conflicted hero like Amuro was a new and unfamiliar concept to American audiences. This is also true of characters like Shinji Ikari from Neon Genesis Evangelion.

The storylines also felt new for the American audience. In American cartoons the protagonist and his people are heroes that are fighting for justice and defeating “evil”. In Gundam, although Amuro and his allies ultimately win the war, the opposing side of the Zeon isn’t necessarily portrayed as “evil.”

Gundam is just one example. Anime introduced Americans to new kinds of stories and characters and even genres that didn’t exist there before. Japanese products used pre-existing formats like games or cartoons or comic books to transmit totally new perspectives to young people around the world, which helped lay the foundation for what I think of as a “New Japonism.”

The Three components of Fantasy Delivery Device

—— So the uniquely Japanese values in the storylines have influenced audiences in the U.S. and other countries as well?

Things like karaoke, Tamagotchi, and Japanese games, anime, and manga were more than hits. They stimulated our imaginations, and prompted new ways of thinking. This in turn shaped people’s tastes, dreams, and even their sense of reality. I refer to products like this as “fantasy delivery devices.”

I believe there are three factors that make a product a fantasy delivery device. I call them the “three ins.”

First, they have to be “inessential” – we buy them out of want, not out of need. They have to be “inescapable” – so popular that they’re part of the fabric of life. And they have to be “influential” – they have to change the way we live, or the way we think about Japan, and often both.

—— Does a product need to meet all three conditions to be considered a fantasy delivery device?

Yes. Here’s a counter-example: cars. Since the 1970s Japanese cars have come to dominate the world market, but in the U.S., a car is often a necessity for life. People buy them because they have to, based mainly on things like cost. So that isn’t a fantasy; it’s hard reality.

The VCR is an even better example. A VCR is certainly inessential, and was also inescapable in the Eighties and Nineties. But it wasn’t influential, because we didn’t consume Japanese fantasies on them. We consumed Western ones. It didn’t change anyone’s perceptions about Japan, so it isn’t a Japanese fantasy-delivery device.

—— Cars and electronics are largely a necessity in everyday life. You say that fantasy delivery devices are products that have an inescapable appeal that have the power to change our perceptions about Japan, but are not necessities. I think we can say a product that is not a necessity can be considered a shikohin, but why do you think it’s so important that they be shikohin products?

Because the consumer is making a conscious choice to get it. Of course there are many sorts of necessities in life, and the choices we make for them also reflect personal preferences. But when it comes to a necessity, customers will inevitably buy things because they have to rather than out of pure desire.

Americans living in the suburbs may need to buy a car out of necessity, even if it is a financial burden for them. It might not be “cool” or represent their values. We might purchase Cup Noodles because there’s nothing else to eat. The criteria is more about survival than it is an expression of our identities.

In contrast, I think we can agree that games, anime and manga aren’t needed for survival. So when we buy them, they are a purer reflection of personal preferences.

We actively choose them based on our own wants and passions. And when we do this it’s more likely that they will influence us as we consume them. This is why only “inessentials” qualify as being fantasy delivery devices, in my book.

—— Why do you think the fantasy delivery devices from Japan became so influential in countries like the U.S.?

Fantasy delivery devices give us unexpected strength to survive in a chaotic world.

As I mentioned earlier, Ukiyo-e and other forms of art that sparked the original Japonism movement were also fantasy delivery devices. They emerged during the late Edo period—a time of profound social and political upheaval in Japan.

Today Japan is again navigating turbulent waters: economic stagnation, a declining birthrate, and other first-world challenges. The United States is facing great uncertainty and political division, too.

What’s interesting is that from ukiyo-e to today, the games, anime, manga and other fantasy delivery devices from Japan that are so popular around the world, were all originally created for the Japanese audience first and foremost. We non-Japanese were secondary audiences.

Ironically, this is the exact reason why fantasy delivery devices have such global impact. They weren’t made for us, so they feel unexpected and new. Japanese creators and consumers sought out nonessential luxuries, shikohin, to help them through chaotic circumstances. As people around the world came to face similar challenges, Japan’s products found new audiences across the ocean. They feel necessary and new – a powerful combination.

The more anxiety and uncertainty we face, the more we need time to relax, escape, and recharge. Of course it is important to face the challenges of life head-on, but it is also necessary to incorporate a bit of fun and play in our daily lives. Japan is great at offering products that do this.

—— You think that Japanese shikohin proved to be excellent tools to relax and escape reality for a moment so that is why they were welcomed by many other countries and cultures?

All countries go through some sort of turbulent times, so of course that itself isn’t unique to Japan. But I do believe the Japanese people have a knack for developing “tools” to help them escape and enjoy life, even in the midst of tough times.

For example, in the Edo period, women wore short-sleeved kimono called kosode. These were everyday wear, but they created various patterns and dying methods, adding an element of preference or shikohin in their daily lives for pure enjoyment. You can also see it in haori jackets, the outer style of which was tightly regulated by the authoritarian Shogunate, but men and women put interesting patterns inside, as a quiet form of personal expression.

So Japan has a history of blending inessential preferences, or shikohin, with daily necessities. Maybe that is where its cultural charm comes from.

From fantasy to reality─ the next wave of New Japonism

—— Now that we are on the subject of shikohin products, what are some shikohin products that have caught your attention recently?

Well, there’s the fad for Japanese teas, particularly matcha, in the U.S. It isn’t necessarily new – Kazuo Okakura’s The Book of Tea was a bestseller in the early 1900s – but I think it’s interesting how the image of Japanese tea has gradually changed.

I think Japanese tea first started booming in the U.S. about ten years back. It began with matcha-flavored candies, then transformed into a kind of health trend. When I first started seeing matcha in the US, it was often in the form of matcha lattes with a lot of sugar, because Americans aren’t accustomed to super bitter flavors.

However, more and more people, especially among Gen Z, are now enjoying matcha in the same way as Japanese people, as-is, without sugar. And the reason for that is because they’re interested in authenticity. They want to experience “real” Japanese culture and “real” matcha flavor.

You can really see this happening on social media. Matcha creates a beautiful, deep-green colored drink, which makes it perfect on camera. So you see influencers putting it in their videos in all sorts of ways. Some even sprinkle matcha powder on their steaks.

—— Now that is a use of matcha you wouldn’t see in Japan.

With the arrival of generative AI, everything can be generated instantly and it is becoming more and more difficult to tell what’s real. I think this is why there’s a growing hunger for things that feel real and authentic. Authenticity is the currency of the internet. But what you see on social media today is less about cultural authenticity than it is about using products that feel authentic.

This is why you see more and more people incorporating Japanese matcha into their daily lives, while simultaneously deviating from how it is “supposed” to be used. It’s authentic as a product, which amplifies the authenticity of the new ways in which they use it, even if they aren’t “authentic” themselves.

—— I guess more and more people are enjoying products that are deeply rooted in Japanese life as well.

For a long time in America, the most popular Japanese foods were things like sushi and sukiyaki, which are of course staples in Japan, but more like foods for special occasions.

As people raised on Japanese fantasies want to experience more “real” aspects of Japanese life and culture, they’re getting interested in really everyday foods. Things like yakisoba and okonomiyaki – foods that are not only eaten at home but also at festivals. And things like egg salad sandwiches from Japanese convenience stores. These kinds of everyday Japanese foods are only going to grow in popularity.

Anime and manga are leading the way here. A lot of hit anime and manga are set in everyday Japan. That’s how most foreigners see into Japanese culture. So the foods and drinks that show up in these anime and manga are likely to spark the next boom.

Bar culture that is returning to Japan and the stories behind Japanese shikohin

—— You think that the future fantasy delivery devices will emerge from more “real” and familiar items of our everyday lives and that they will change the global perceptions and views of Japan?

In terms of “influencing” I think cocktail culture is very interesting, the way the influence bounced between the U.S. and Japan and back again.

Cocktails originated in American bar culture, spreading globally after World War I and becoming especially popular after World War II. American-style cocktails came to Japan during the Meiji period (1868–1912), via international hotels, but it wasn’t until the Taisho period (1912–1926) that they began to gain widespread recognition among average Japanese.

What’s interesting is that although Americans invented cocktail culture, the modern-day incarnation of it was deeply influenced by Japanese mixologists.

The reason dates back to Prohibition in the United States. Alcoholic beverages were totally banned from 1920 to 1933. As a result, American cocktail culture—which had been flourishing—came to an abrupt end. Although Prohibition was eventually repealed, cocktail culture in the U.S. never fully returned to its former glory.

It wasn’t until around the year 2000 that signs of a cocktail revival began to emerge in the United States. And you can attribute this resurgence to the influence of Japanese bar culture, which never went extinct, and quietly continued to evolve over the decades.

There’s a perspective that Japanese cocktail bars in the Ginza and such represent a kind of “time capsule” —preserving that Taisho era cocktail culture, maintaining classic recipes and styles. At the turn of the Millennium a new generation of American mixologists turned to them to re-learn the forgotten techniques.

Today, cocktails made with sake and shochu are gaining popularity in the U.S. as alternatives to traditional spirits like gin and vodka. I think that might be the next big boom in cocktail culture.

—— Perhaps content that did not necessarily originate in Japan and traditional shikohin products both have the potential to spread across the globe when they meet the conditions of fantasy delivery products.

Japanese shikohin products have stories to them that are based on tradition and history.

The story behind a shikohin plays a significant role in its perception of authenticity. Japanese of course continue making inessentials for themselves, and Westerners continue to find them. So I think this cycle of blending the familiar with the unfamiliar, the new and unknown will continue. Japan has a real ability to create products that are compelling, not only because of their quality but also because of their stories.

(Special thanks to BREWBOOKS)

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Born in Toyama, Japan in 1990. Writer/Editor ←LocoPartners ←Recruit. Graduated from Waseda University, School of Cultural Planning. Writes for “designing,” “Slow Internet,” and other magazines. Editorial partner of “q&d. Likes basketball and coffee, and is a sucker for standing bars, snack bars, idle talk, and people who roll their own cudgels.

Editor, Writer, etc., for PLANETS, designing, De-Silo, MIMIGURI, and various other media.