One of the products that has fostered the richest shikohin ecosystem in Japan is tea.

Far beyond being a simple beverage, tea has become part of a centuries-old tradition. The culture of the tea ceremony has woven itself deeply into Japan’s politics and cultural identity.

Yet, the economics surrounding this tradition are rarely discussed.

Naoki Ota, Assistant Professor at Doshisha University’s Faculty of Economics and a cultural economist, is one of the few researchers directly examining the economic structures of the tea ceremony.

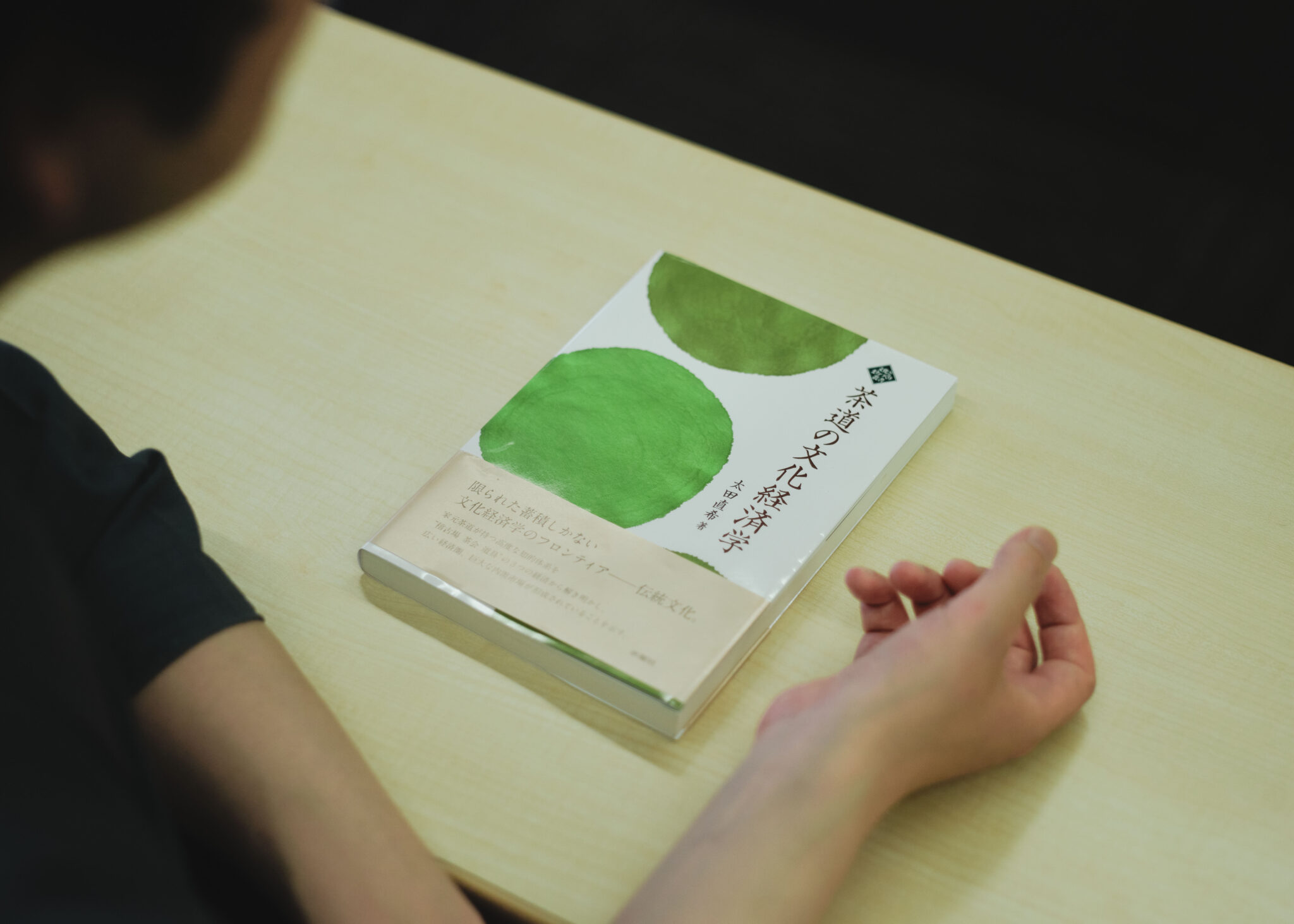

In 2024, Ota published his first book, The Cultural Economics of the Tea Ceremony. In it, he explores not only the cultural dimensions, such as the Iemoto system, which oversees licensing and instruction, and the spirit of wabi, but also the economic dynamics from three perspectives: tea classes, tea gatherings, and tea utensils.

How do these economic systems actually function? And why has tea succeeded in building such a resilient ecosystem as a shikohin?

We spoke with Ota about the economics of traditional culture, and what they reveal about the future of shikohin goods.

Unraveling the Cultural Economics Model of Tea

── You are an expert in the cultural economics of the tea ceremony. What exactly is “cultural economics” in the academic field?

Cultural economics is a relatively new academic field that originated in England and the United States. In Japan, it has a history of about 30 years.

Broadly speaking, there are two fundamental approaches to cultural markets within this field.

The first examines markets based on originality, for example, the trade of unique works such as paintings or other artworks. The second focuses on markets rooted in reproducible technologies and intellectual property rights, such as film, or other content that can be mass-produced. Research in both approaches often centers on how cultural products are distributed and ultimately reach consumers.

In Japan, cultural economics has also developed a strong focus on “creative cities” or urban strategies that aim to revitalize local economies and tourism by linking arts and culture to community development.

More recently, the field has begun to explore Japan’s own distinctive cultural-economic models and aims to share these insights internationally. Because of my background in the tea ceremony, I have chosen to focus my research on this traditional cultural practice.

── So your goal is to unravel the cultural economic model of the tea ceremony?

The economic aspects of the tea ceremony have rarely been examined in depth.

In my book The Cultural Economics of the Tea Ceremony, I divided the tea economy into three parts: the economics of tea classes, tea gatherings, and tea utensils. This was the first attempt to present the tea ceremony in such a systematic framework.

The tea ceremony is a profound and multifaceted culture, and at first it was difficult to represent it schematically. Many elements overlap. For example, the economics of tea utensils are often deeply connected to the economics of tea gatherings. Still, I believed that each had its own definable system, and that analyzing them separately could open up new perspectives.

I wanted to begin by addressing the question of how we should understand the tea ceremony itself, and then proceed to analyze it in relation to economics. As I will explain in more detail later, I believe that the philosophical systems underlying the tea ceremony are closely reflected in its economic systems.

I take pride in being the first to depict the culture and the economics of the tea ceremony together as one integrated system.

── I know you originally practiced the tea ceremony, but what sparked your interest in it in the first place?

My grandmother practiced the tea ceremony, so it was always a familiar presence in my life. But I only began to truly engage in it after moving from Tokyo to Kyoto for university.

In Tokyo, I was drawn to content-based entertainment such as theater and live performances. Kyoto, however, offered far fewer of those experiences. Instead, what I found was an extraordinary abundance of tea ceremonies.

It was then that I realized tea ceremonies might be the ultimate form of entertainment. For the first time, I began to see the practice through my own eyes, and that was when I decided to start taking lessons.

Tea ceremony as a multi-faceted system

── Were there any other studies on cultural economics of Japanese traditional culture beyond the tea ceremony before yours?

One of my advisors, Professor Tadashi Yagi, conducted research on traditional Japanese music. His work was essentially the only prior research in this field that focused on traditional Japanese culture. In his studies, he also discussed the Iemoto system of the tea ceremony and highlighted some of the issues surrounding it.

For example, under the Iemoto system, the master (iemoto) maintains a group of disciples (shachu) and is obligated to allow them to perform in recitals, even if their skills are not yet sufficient. In performance-based traditional arts, disciples usually practice with the goal of appearing on stage or in recitals. If they are not permitted to perform, they often lose motivation and stop attending practice.

As a result, less skilled practitioners may still appear on stage, lowering the overall quality of performance. When audiences encounter such lower-quality performances, their appreciation for the art diminishes, creating a vicious cycle.

This is why, in many traditional performing arts, significant attention is given to how best engage audiences and attract new practitioners.

── What does this tell us about the tea ceremony in the framework of traditional performing arts?

In this respect, I believe the tea ceremony has been remarkably successful in maintaining a well-managed system.

First, the structure of tea classes is highly sophisticated. They serve as places of learning for disciples while also providing an avenue of compensation for the tea master. These classes are further connected to a certification system, in which the headmaster issues qualifications as proof of achievement.

Moreover, the tea ceremony is not limited to the framework of a performing art. The act of preparing and serving tea is only one element within a much broader cultural practice. The components that together constitute the tea ceremony are exceptionally diverse.

── To define that diversity you divide the economics of the tea ceremony in three economic systems. The economics behind students paying for lessons from a tea master for the tea lessons, the economics of collecting fees through tea gatherings, and the economics of selling and buying tea utensils.

Yes. Through my research, I found that these three systems form the major economic pillars of the tea ceremony. They do not exist in isolation; rather, they are deeply interconnected, together creating an exceptionally resilient structure.

In fact, the world of the tea ceremony today encompasses hundreds of thousands of participants, sustaining a remarkably robust system. At its core is the Iemoto system, which serves as the foundation that links these three economic activities.

This kind of comprehensive system is not necessarily found in all traditional arts.

Being pushed to edge of resignation helped spread the tea ceremony culture

──In your book you have a particular focus on the “wabi” as the philosophical core of the tea ceremony.

The word wabi carries many interpretations, changing in nuance depending on who uses it. For people outside Japan as well, wabi has become an evocative term that symbolizes Japanese culture.

Yet, little attention has been given to how this aesthetic concept intersects with economic systems.

In my book, I turn to Sen no Sōtan, the grandson of Sen no Rikyū. Sōtan, whose three sons later established the three main Sen family lineages (Mushanokōji Senke, Omote Senke, and Ura Senke), dedicated himself to the pursuit of wabi tea.

Sōtan’s first disciple, Yamada Sōhen, once explained: “The character for wabi is pronounced ta and used in the compound ta-sei (wabi-sabi). It signifies a state of mind that has lost its purpose, a condition where one cannot act as one wishes, marked by dissatisfaction.” In other words, when resources are scarce and one is brought to a standstill, one enters a state of resignation. Unlike the relatively prosperous era of Sen no Rikyū, Sōtan lived under harsher economic conditions, and it was this reality that shaped his understanding of wabi.

──The edge of resignation.

In the past, imported luxury goods from China, known as Tang goods, were regarded as the pinnacle of prestige.

However, the Senke schools of tea favored Raku-yaki tea bowls, or handmade bowls imbued with warmth that embody the spirit of wabi tea.

In other words, they consciously relinquished the pursuit of prestige and luxury. This very act of resignation is what defines wabi.

Equally important, the wabi tea movement played a crucial role in spreading tea ceremony culture.

The wabi-style tea hut, a simple, rustic space, incorporates elements of everyday country life, such as the hearth of a rural home, into its design. This creates a “one-seat establishment” (ichiza konryū), a principle in which host and guest become one, co-creating the space and the moment together, thereby fostering a deeper sense of connection.

── The resignation of maintaining the high status of luxury tea utensils is what led to a broader audience and higher accessibility to tea?

Before the era of wabi tea, tea ceremonies were expected to use refined, high-end utensils, and careful observation of these objects was an integral part of the practice.

However, with the rise of wabi tea, the doors to the ceremony opened more broadly. In my book, I highlight a symbolic example: an exchange between Sen no Rikyū’s grandson, Sōtan, and a member of the Konoe family.

Konoe Hisatsugu, a leading court noble, requested that Sōtan demonstrate a tray-style tea ceremony. At the time, the tea caddy placed on the tray would naturally be expected to be a luxurious, high-status piece. Yet Sōtan placed a new, modest tea caddy, likely made in Seto or another domestic source, on the tray.

This choice would have been unthinkable by the standards of the day. It must have been quite shocking at the time, which is likely why the episode was recorded and has survived to this day.

── What kind of new tea culture emerged when the practice became more accessible?

The November Tea Ceremony’s New Year celebration brings host and guest together to honor the joys of the hearth season, embodying the very essence of wabi tea. This gathering is not about displaying status or luxury; rather, it is a celebration of the arrival of the wabi tea season, a tradition meant to be accessible and welcoming to many.

Can the tea ceremony become a global culture?

── Japanese tea is now attracting a lot of attention from other countries. For example, matcha is being traded at very high prices in Europe and America. What do you think about this trend?

There was a similar matcha boom in England in the past.

England has many garden and tea traditions like Japan, a connection noted by former Shizuoka Governor and researcher Heita Kawakatsu. Japan and England have long shared a cultural affinity. Yet, I have never encountered an example where the Japanese tea ceremony has been properly exported and firmly established in another country.

I have also heard that obtaining Japanese tea is becoming more difficult in China. Even in Japan, tea shops have had to limit purchases, often to two items per customer, to prevent hoarding. With growing demand, efforts to export more tea and invest in production facilities are underway.

At the same time, low-quality counterfeit teas and imitations of tea ceremonies are increasingly common in China. One recent, striking example involved a historically significant Chinese site sending representatives to Japan to study the “Yotsugashira Tea Ceremony” at Kyoto’s Kennin-ji Temple. Although they reportedly learned the method correctly, when they returned, they developed a version that resembled a Chinese-style Yotsugashira and even registered it as a “World Heritage” event.

These incidents highlight the difficult reality of establishing Japanese tea as a truly global culture. Some argue that tea must be modernized for international audiences, omitting charcoal because it’s hard to source, or forgoing tatami mats because few people can sit on the floor today.

I personally have concerns about this approach. Surely there are individuals abroad with the same dedication and appreciation for tea as Japan’s traditional connoisseurs. The real challenge, I believe, is how to attract these people and invite them into the world of Japanese tea, where the spirit and culture of Japan can truly flourish. I think this will become an increasingly important issue in the future.

── Speaking in the context of inbound tourism, I hear that the tea ceremony is a popular experience among visitors from overseas.

That’s true. Although I often wonder why the tea itself is treated as a luxury item when exported overseas, yet tourists paying for a tea ceremony experience in Japan are charged so little. People will pay tens of thousands of yen for premium matcha, but only a few thousand yen for an authentic tea ceremony experience.

I’ve personally worked part-time running tea ceremony experiences for tourists in Kyoto. The hourly wage was just over 1,000 yen, while the experience cost around 3,000 to 4,000 yen per person. Once overseas tour companies are involved, charging more simply doesn’t work.

I once collaborated with a Kyoto temple and a local tour operator to try something new. We carefully calculated costs for a three-party project, and the reasonable price came out to around 7,000 to 8,000 yen per person. Yet even that proved difficult. Overseas clients insisted anything over 10,000 yen per person was unacceptable. Ultimately, standard tours remain at 3,000 to 4,000 yen.

Currently, demand seems limited to tourists seeking “a small souvenir to take home.” Very few are willing to truly immerse themselves in a tea ceremony. I believe there is a significant gap between casual interest and genuine appreciation. The real challenge is how to cultivate foreign tea enthusiasts who come specifically to experience the tea ceremony itself.

Tea is globally produced

── Lastly, I want to ask about the future trends in shikohin products. Do you think tea can be defined as a shikohin product?

For Japanese people, tea has always had a strong shikohin, or luxury product, aspect to it.

Historically, tea was first consumed as medicine, but over time it evolved into something to be enjoyed within the special space of the tea room. It wasn’t just about the flavor or health benefits; the entire experience of engaging with kochu, the world within the teapot, embodied the shikohin aspect of tea.

In the past, people would drink tea, smoke tobacco, and drink alcohol together. A kind of stimulant and indulgence party, complete with caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol.

Today, however, many people drink tea like barley tea or sencha simply to quench their thirst. What was once a luxurious, indulgent shikohin has increasingly become an everyday beverage in modern life.

── With these changes in mind, what do you think will be important for shikohin culture in the future?

If we want to create new shikohin experiences, I believe it is essential to involve elements beyond just flavor and consumption, much like the tea ceremony.

For instance, there is a culture known as senchado, where people brew and enjoy sencha instead of matcha. From the utensils to the practices themselves, it forms a carefully crafted world in its own right. For such new shikohin to truly take root, it is vital that these elements are thoughtfully interconnected.

Furthermore, something that tea enthusiasts all say is that tea has a magical attraction.

── A magical attraction?

I think this magical attraction of the tea ceremony is tied to its three systems—practice, gatherings, and utensils. Each system carries its own charm and draws people in.

In tea gatherings, the setting is carefully crafted with seasonal flowers, scrolls, and vases, all chosen to suit the guests and the occasion. One of the pleasures lies in deciding what to use and how to arrange these elements.

In the practice setting, there is the concept of the “one-seat establishment” (ichiza konryū), which creates a space for people from different backgrounds to connect. Those who share a love for tea can interact across social class and status, discussing tea gatherings, utensils, and techniques with others they’ve met through the practice.

── Shikohin experiences are shaped by people, places and experiences.

What’s truly fascinating is how this world never reaches a dead end. The phrase “once-in-a-lifetime encounter” is perfectly fitting—no two moments are ever exactly the same.

Preparing and drinking tea may seem like repeating the same actions, yet each time offers subtle differences to savor and appreciate.

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Born in 1990, Nagasaki. Freelance writer. Interviews and writes about book authors and other cultural figures. Recent hobby is to watch capybara videos on the Internet.

Editor, Writer, etc., for PLANETS, designing, De-Silo, MIMIGURI, and various other media.