“I wanted to make a delicious tea that is safe for my family to drink every day.”

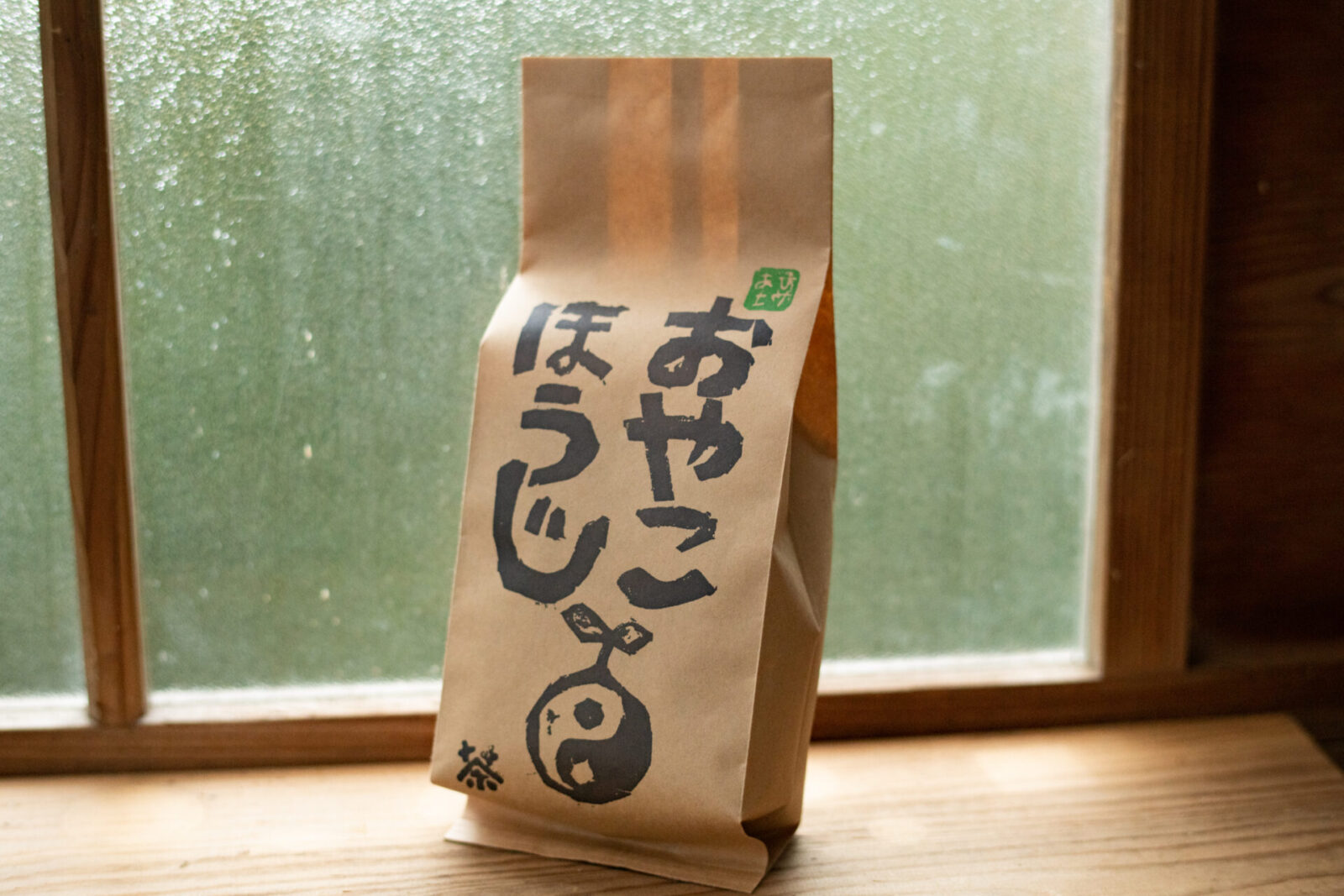

Hide Koganei and his wife Asuka run Asahiya, a tea business where they grow and process their own tea. They sell two types of tea: “Oyako Houji” and “Koganeiro.”

After living in a self-sufficient commune with no electricity in Thailand, they now live a natural life in Nara. Their personal philosophies and the cultures of the Nara region are combined to create a warm and inviting tea.

Growing tea organically with natural farming methods

When we visited the Koganei household, Hide and Asuka welcomed us into their hut where they were roasting tea leaves by hand using fire from wood. The sound of the crackling firewood was comforting. Their self-built hut was filled with the aromatic scent of roasted tea leaves.

first part:From Working in Tokyo to Living Without Electricity in Thailand. This is How We Became Tea Farmers

The two have a tea farm in Nara City of Nara Prefecture.

Nara City is known for its Yamato tea grown in the lush green mountainous areas such as Tsukigase and Tahara districts. Director Naomi Kawase’s “The Mourning Forest” was shot in the Tahara region and won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival. It was an impressive film which featured scenery of beautiful tea fields.

The Koganei’s tea farm is also in the Tahara region, and they do all the work of making themselves from growing to processing their tea leaves.

The most popular tea they make is their “Oyako Houji” and we asked them about the process of making it.

Hide focuses on three points for making his tea. The first is to minimize the negative impact it has on the natural environment.

“I wanted to focus on the methods I used for processing the tea leaves. In general, tea factories use a lot of heavy oil to make tea. I wondered what kind of effect that has on the environment. I wanted to make tea with as little negative impact on the earth as possible.”

He decided to grow his tea organically and use natural farming methods. For processing, he also chose the method with the least environmental impact. The tea “Oyako Houji,” has a deep flavor and soft sweetness that comes from “okumidori,” a species of tea indeginous to the area.

Bringing back “parent and child” bancha in Nara

His second focus is regionality.

“As I learned more about Japanese tea, I learned about the existence of local teas, such as Kama-roi green tea in Kyushu, which is stirred dry in a pot, the Awa-bancha in Tokushima, which is made by boiling tea leaves in a pot, packing them in a barrel, and fermenting them with lactic acid bacteria, and Go-seki tea in Kochi, which is a black, square-shaped fermented tea.”

Lately, deep-steamed tea has become popular and the most commonly produced tea in Japan, but he felt it was too uniform and boring. One day a local tea farmer told him, “In this region, we used to make ‘oyako bancha”.

“What is oyako bancha?”

Oyako bancha is a tea where the tea leaves are not harvested until they grow large in the summer. They harvest both new leaves and old leaves at the same time, so that is why it is called “oyako,” meaning “parent and child.” It was enjoyed in Nara and Kyoto in the past, and is also known under the name “Takuricha.”

Waiting until the summer to harvest means that the tea farmer loses one harvesting season to pluck new tea leaves, which is a large income source. In the tea business, it is common to harvest four times a year: at each stage of growth from new leaves to older leaves.

Since one harvest for new leaves is lost, there are no longer any tea farmers in Nara City that produce oyako bancha tea. Hide identifies himself as a “hyakusho,” which is a traditional term for Japanese farmers and literally means “a man with a 100 surnames.” Hide also works in forestry, so he decided that one harvest a year would be enough. He appreciated the history and culture behind oyako bancha.

“In normal tea production, only the best part of the tea leaves are used after sifting, but it is more healthy to drink tea that uses the whole tea tree. I liked the concept of ‘parent and child’ in oyako bancha and the fact that it uses the whole tea leaf, stem and all.”

The story behind creating Oyako Houji tea

Hide’s third focus is creating tea that can be enjoyed safely on a daily basis for his family.

“I decided to try to roast the oyako tea leaves in a way that will make it easier to drink everyday,” he says. In general, houji tea (roasted green tea) does not use the new leaves. Houji tea is made by roasting bancha (tea harvested after the new leaves). Why did Hide decide to make his tea into a roasted houji tea?

“San-nen bancha, which is made by harvesting tea leaves that have been grown for three years, is better for your health because it has less caffeine and tannin. But really, I simply prefer the taste of roasted houji tea.”

The Koganei family has two children. Asuka wanted to make tea that the children could drink as well.

“I told Hide that it would be nice to have tea that can be enjoyed by the whole family. Houji tea, which is roasted at a high temperature, contains less catechins and caffeine than higher grade sencha, and has less astringency and bitterness. Houji tea is a tea that can be enjoyed by children too.”

When Hide tried making it, he found that it tasted even better than houji tea he had tasted in the past, and the children enjoyed it as well.

In 2013, he created the “Oyako Houji” tea as a tea that is both made from “child and parent of tea leaves” and made for “children and parents to enjoy together”.

Hide smiles as he shares, “I have had customers tell me that their children do not drink other teas, but enjoy drinking this tea. It made me very happy.”

As the years passed, his production methods improved. His latest method of making “Oyako Houji” is as follows.

“In June, around the summer solstice, we pick the tea. We do not wash it and immediately steam it in a machine at a nearby tea factory, and then we rub and dry it at the same factory. It’s not that I have the factory do all the work. I work with them. After that, I store it at home and roast it for an average of one and a half hours depending on the climate and humidity. Lastly, I let it sit overnight, and it’s complete.”

Houji tea is usually roasted using gas or electricity for heat. Hide started off using a large coffee bean roaster, but changed his method to roasting by hand on top of a wooden fire.

In the hut he built himself, he silently roasts the tea leaves for an hour and a half.

With the sounds of the tea leaves mixing, a coffee-like aroma fills the room and the tea leaves begin to change color.

The taste is both savory and refreshing. One could drink it every day without tiring of it, and it leaves a cool feeling on your tongue that is neither too strong nor too weak. It makes the perfect “family tea.”

If you use a teapot, “Oyako Houji” tea can be enjoyed for two infusions. Hide’s personal favorite is making it cold-brew. Asuka likes to make it into a chai and pouring it over rice to make “ochazuke” (rice with tea).

“Koganeiro,” a golden tea for special occasions

While “Oyako Houji” is a tea to be enjoyed everyday, the “Koganeiro” is a luxurious tea meant to be enjoyed on special occasions.

“After working in the tea industry for 10 years, I wanted to make a luxury tea that I could pour all of my past experiences and skills into. It was a way of challenging myself to prove that I could make a special tea.”

As if to reexamine the steps he took that led him on his journey with tea, he studied his tea and began developing “Koganeiro.”

“My name Koganei shares the character for ‘gold’ in ‘Koganeiro.’ I came up with the name first because my name made me think of ‘a golden color tea.’ I imagined that, in order to create a golden colored tea, a blend of black tea and oolong tea would work. I made countless prototypes using an original processing method to create this tea. I wouldn’t say that the development process was stressful. It was more fun for me.”

The characteristic of this tea is that it is hand-picked, hand-rubbed, and semi-fermented by hand without going through factories. The tea only contains tea leaves indigenous to the area. Even the local tea farmers do not know the names of the indigenous varieties, and Hide says that they are yet to be classified.

In May, he picks only the new leaves and leaves them out to dry slowly in the shade. When Hide feels that the leaves start emitting a nice aoma, he begins rubbing them. Raw tea leaves begin to turn brown as they ferment.

He then dries them further in the shade, and when they start smelling good again, he roasts them in a steel pot to stop the fermentation and rubs them again. Hide repeats this process of roasting and rubbing and drying until the final product is done. He lets the final product rest for about one month and begins selling the tea around in July.

The changing colors and flavors through its 4 infusions

Hide used a Chinese tea set to serve us his “Koganeiro” tea.

“Some people enjoy making just one tea infusion to serve it like black tea, but my personal recommendation is to infuse and serve it little by little. It can be enjoyed for three or four infusions.”

Of course, the flavors change with each infusion. The first infusion has a strong and sweet aroma like Dong Ding Oolong tea, with a soft flavor that stays in your mouth, almost like a fruit. The color is like a golden candy.

“Personally, I like to make the first infusion very lightly and really enjoy the second infusion. The second infusion is the true flavor of ‘Koganeiro’ for me.”

The second infusion has less aroma, but the sweetness is enhanced. The third infusion has an even more mellow flavor and a very clear sweetness.

Rejecting mass production and unnecessary markups

Asuka says that “Koganeiro” is a special tea.

“A lot of labor goes into making it and we can only make a small amount. Since it sells well, there is demand to increase production every year, but only Hide can make this tea and he only has a limited amount of time to work on it so we cannot mass produce.”

Hide adds, “Koganeiro is sold at 1100 yen for 30 grams. Our customers have told us that we can charge more, but raising prices means it will only be accessible to rich people so I don’t want that. I don’t like rich people (laughs).”

The way they sell their two products is also unique. In addition to their online shop, they ask the stores that they personally like to sell their tea, and are slowly increasing the number of stores that handle their products. Right now, there are about 20 such stores in Japan, including one store that is run by a friend they made while living in Thailand.

On any kind of special occasion, we always have some kind of special drink. In Nara, we found two teas that bring joy to our palate and hearts that can be enjoyed 365 days a year.

Photo:Yuko Kawashima

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Editor and writer. Freelance from 2003. Specializes in local and social issues, and the medical field. Reporting and writing for the magazine “Sotokoto” and web media “Through Me”. Editor for books including “Like a Rolling Komuin (Civil Servant)” by Hiroaki Fukuno and “Community Nurse” by Akiko Yada (both published by Kirakusha). Moved from Tokyo to Nara in 2017. Holds an yearly course on the “basics of editing” for the general public in Nara Prefecture.

Editor and creator of the future through words. Former associate editor of Huffington Post Japan. Became independent after working for a publishing company and overseas news media. Assists in communications for corporates and various projects. Born in Gifu, loves cats.