Food items such as alcohol, tobacco, tea and coffee are not consumed for any nutritional value, but for enjoyment. These food items are referred to as “shikohin.” Why did mankind pursue these items that, at first glance, seem to have little purpose in survival?

“Shikohin” is a term that is difficult to translate outside of Japan and unique to the Japanese language. It is said that the first person to use this term was Ogai Mori, who described “shikohin” as something that is “a necessity in life” that is also “a poison” in his short story “Fujidana” published in 1912. Being both a poison and a medicine, “shikohin” is surrounded by ambiguity. In the DIG THE TEA series, we will explore modern day “shikohin” and its role in our society through interviews with leading experts both in and out of Japan.

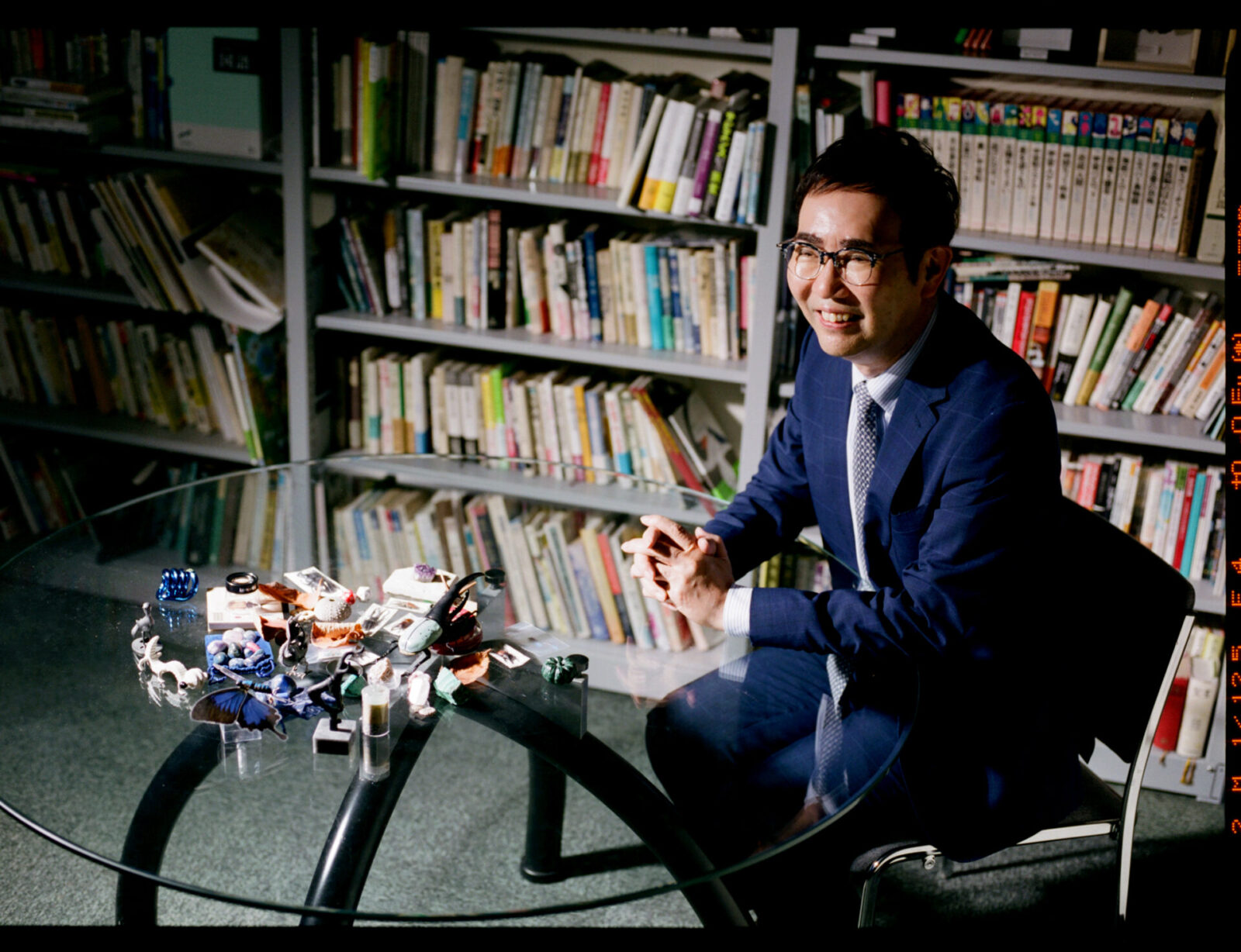

For the sixth installment of this series, we visited biologist Shinichi Fukuoka. In Part 1 we discussed “logos,” or the power of words that human beings have developed to attain freedom, and “physis,” which is “nature,” or the natural state of life. Based on these two concepts, we talked about the role of “shikohin” in returning to the ways of “physis” in a world that has become overrun by extreme “logos” mentality.

In Part 2, we will explore ways to regain a sense of wonder in order to “relive” our later days in life through re-examining “shikohin” as something that reminds us of the pleasures in life that give us the sense of acceleration, in our modern world where the way we sense time is changing.

Interview&Editing: Masanobu Sugatsuke Co-Editor: Masayuki Koike & Takumi Matsui Photos: Mayuko Sato

Part 1 of 2 》Shikohin: The Connection Between Logos and Physis. Interview with Biologist Shinichi Fukuoka

Reacquainting with the textures of life through shikohin

── You often talk about the complementary nature of life, that life is like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle where life complements each other and supports each other and this is what sustains life in a flow of dynamic equilibrium. In terms our theme of “modern shikohin,” do you think that there is a complementary nature in the relationship of food we intake for nutritional sake and for “shikohin” which has no nutritional purpose?

I think that there is a continuum between the two. The physiological effects that we get from “shikohin” are comparable to certain neurotransmitters and metabolites that the body inherently has. Products such as nicotine, caffeine, and alcohol are similar to certain neurotransmitters and metabolites that are derived from certain food sources. In other words, “shikohin” are an extension of food components and can be considered to be on a continuum with the three major nutrients or vitamins needed for our bodies.

──You mean that “shikohin” are on a continuum with the foods and nutrients we need in order to survive?

From a different perspective, I believe “shikohin” is like music and it is a device that helps human beings rediscover the sensation of being alive.

I once had a discussion with musician Ryuichi Sakamoto about the origins of music. According to the basic theories in the history of civilization, music is said to have been developed from the sounds of birds and insects singing and communicating with each other. In other words, music was born as a tool for communication. However, I believe there is another aspect to it. I think that music was more of a personal act.

The basis of music is rhythm. The wavelengths that are created by musical instruments and the rhythms made by percussion instruments are similar to the sounds inside of our bodies that we inherently possess as living organisms. The human body emits various sounds and vibrations from the heartbeat, pulse, breath, brain waves and even the rhythm of sex. However, when we are so consumed in our busy daily lives, we forget that we are ourselves creating and inscribing such sounds.

I think that music played a role to externally reference those sounds. We feel the sounds of percussion or string instruments become synchronized with the sounds inside our own bodies. The very act of wanting to move our body to the rhythm of music is the act of using external sound as a metronome to make our own body a musical instrument.

I think music is a very personal way that human beings created to remind ourselves that we are in fact alive in the moment. Sakamoto and I talked about this. I think that “shikohin” acts in the same way, and the act of drinking coffee or smoking cigarettes gives us a moment to rediscover “physis.”

── I myself am a coffee lover and I have many friends in and out of Japan that are baristas or coffee roasters. I find it interesting because all of them describe brewing and drinking coffee as like a ritual that helps them rediscover themselves.

Smelling a fragrance is much like a ritual to rediscover your sense of smell, and tasting the bitter and sour flavors make you vividly aware of your sense of taste. The arousal that comes from drinking caffeine gives us the awareness of our brains being active. Enjoying “shikohin” are rituals that gives us the means to rediscover the punctuations and textures of life itself.

The source of human pleasure

── You often make references to philosopher Henri Bergson’s views on life. In Bergson’s book “Creative Evolution,” he says that, while material substances have a downward slope, life tries to climb upwards. I think that enjoying “shikohin” is one of our means of going against the law of entropy and it gives us the energy to climb upwards.

Yes, I think that Bergson is a philosopher that clearly approaches the reality of life as “physis.” Even a shiny piece of metal will eventually rust and magnificent architecture eventually weathers. Orderly things disintegrate and the law of entropy cannot be resisted. Yet somehow, only life itself seems to manage to climb back up.

However, even Bergson did not describe how life manages to climb back up and he limited his discussion on the topic to a spiritual discussion of “élan vitale (leap of life).” I offer my idea with all due respect, which is “getting ahead and destroying.” We must anticipate the law of entropy before it strikes us, and take the initiative to destroy it ourselves. By getting ahead, we buy some time to build ourselves back up.

In other words, the phenomenon of life is the act of creating time itself.

Earning negative entropy means that we are creating more time. This is in a way an act of out-running time and accelerating ourselves. In fact, all the pleasurable sensations that humans experience are feelings of acceleration. Whether it is speeding in a car, riding a roller coaster or sexual pleasure, it is all a sense of acceleration.

When we outrun time, we get a sense of acceleration. Climbing up a downward hill, or “living” itself is acceleration. “Shikohin” acts as reminder of this acceleration in a mild way.

Rebooting life in our later years

── In December 2019, I published a book titled “Away From Animals And Machines.” I interviewed a total of 51 researchers, entrepreneurs, and academics in Japan and abroad to find out whether or not AI will make humankind happier. The main reason I decided to write this book was precisely because I was contemplating this idea of time. I often see discussions on how the way we will work in the future will drastically change. It seems to me that in the background of these discussions are the two major changes in time that humans living in the 21st century will have to face. One is the increase in our life expectancies and the other is the reduction in working hours due to the implementation of AI. I think that these two changes will make the amount of available time we have in our lives significantly longer.

I think the act of enjoying “shikohin” is an act that subjectively stretches out or shrinks how we experience time. How will humans deal with time in a world where our lives are becoming longer and we are spending less time working? I believe this is an important question for us in the 21st century. As it becomes more important for us to proactively control our time, I think that “shikohin” will play an important role.

I think about this issue a lot as well. In an age where we are told that we will live 100 years, how should we live out our days? Genzaburo Yoshino once addressed young people with the question, “How will you live your life?” Those of us who are in our middle-age years are needing to ask ourselves this same question.

The answer to the question is quite simple, and it is to “relive.” The question is, how do we do that?

I think everyone faces a so-called mid-life crisis at some point in their lives. I mentioned my experience in the first part of this article, and it was when I was faced with a dead end in my “logos” style research. From there, I shifted my focus to the exploration of the dynamic equilibrium of “physis” and began to pursue the sensations that I had as a young boy who was fascinated by insects. I believe that if we are able to experience a moment where we are brought back to our roots, we are able to relive and make the second half of our life more meaningful.

One good example that comes to mind is the life of my favorite painter, Hokusai Katsushikia. At the age of six, he developed a strong desire to draw everything he saw and ever since he worked as a painter because he loved doing it. However, at the age of 50, he looked back on all his past work and realized that he was not fully satisfied with any of them. However, he maintained his sense of wonder that he experienced as a young boy and continued to challenge himself to achieve satisfaction. When he was 70 years old, he created his masterpiece, “The Great Wave off Kanagawa.”

It is never too late to start something. Everyone has the potential to make their talents bloom, whether they are 50, 60-years old or even older.

── Still, not everyone can become like Hokusai. Do you have any advice on how people can make their talents bloom again later in life?

One important thing is to really think about your roots. In my case, I was a young boy who loved insects and when I saw a butterfly come fluttering out of the pupa, I wondered “what is life?” That was my sense of wonder. For Hokusai, it was the sensation that he felt when he started drawing at the age of six. It is important to cherish these feelings and use the skills you have mastered in the first half of your life as a foundation to keep on climbing.

Time in terms of biology is always changing because it is made up by the acceleration of going up and down this slope. This is why subjective time is elongated and contracted. A clock ticks away physical time, but the time we create through our living ego can be lengthened or shortened. This is why everyone has the capability to relive their lives.

In an age where we can expect to live 100 years, the question of how we choose to live our days is a big topic for humankind. Perhaps smoking a cigarette while contemplating this will help (laughs).

Childhood playtime: what makes humans human

── I don’t think it is easy to experience a sense of wonder. How can we go about finding it?

Sense of wonder is not something you look for, but it is something you remember. It is something that every one of us has experienced in the past and we just have to rediscover it.

Biologist Rachel Carson is known for her book “Silent Spring” and she wrote a short novel titled “Sense of Wonder” before she passed away. According to Carson, a sense of wonder is a “sensitivity to surprise” and it is naturally present in children and not something that needs to be found. It is “a priori” that exists before we study and learn anything from books. She says that every child has a moment where they experience the world and are amazed at its exquisiteness.

In my case it was bugs, but it can be fossils, astronomy, art, paintings, sports, and even man-made artifacts such as computers. All of this can stimulate a sense of wonder. We all have something in our lives that we are destined to discover. However, Carson says that as we grow older, these things get lost in our boring jobs and we easily let go of our sense of wonder and forget them.

I would add that our sense of wonder fades as we grow older because we become more sexually awakened. This is an unavoidable part of our need to reproduce, but this is also why childhood is so important.

Childhood is actually a very special time that is very unique to humans. No other creature takes more than a decade to reach sexual maturity. For other living things, childhood is a linear time before reaching reproductive age, and their main objective is to consume as many nutrients as quickly as possible to enlarge their bodies to reach sexual maturity. Monkeys reach reproductive age at five to six years, and rats are ready to mate at merely six to eight weeks. However, only humans have such a long childhood, which lasts more than a decade before reaching sexual maturity.

── Why do humans have such a long childhood?

That is a big biological question that we do not have an answer for yet. However, I believe that it is this time in childhood where we are free from sexuality, that is the essence of what makes us human.

Because we are not busy fighting with other rivals for sexual partners or finding our partners, we have the time to play. Playtime allows us to cooperate rather than fight. Rather than time spent on securing food or protecting our territory, we have time for simple explorations of curiosity and futile play.

Playtime is the most important time for learning about the world. What we learned from playing is what led to the creation of all cultures. As historian Johan Huizinga and sociologist Roger Caillois have argued, playtime is the social, economical and cultural foundation of humankind.

Rediscovering our sense of wonder in our later years

── I see. The long period of playtime that we experience in our childhood years creates the foundation for all human activities.

Our sense of wonder is concentrated in what we encounter in our childhood years. In the first half of our adult lives, we forget about this and are busy creating a financial foundation to live our lives, or raising children and maintaining our families. It is a “logos” oriented life. However, once we are free from those responsibilities in the later part of our lives, we can return to our roots and remember our childhood dreams. I think it is okay to just do what we enjoy.

── This may be an unpleasant question, but what should one who experienced a difficult childhood do?

Of course there are those who experienced poverty or abuse in their childhood years. However, I believe all people have a sense of wonder inside them, no matter what. It may be a memory of seeing a beautiful starry sky while crying at night, or a small flower or bug on the side of a street. Any memory that we cherish has the ability to give us the opportunity to relive our lives in our later years.

── Considering how most people live very busy lives in the city, I imagine it is difficult to keep replenishing our sense of wonder.

Humans are creatures with imagination, so we can experience and imagine going to other places by reading books, going on the internet, looking at maps and watching videos. I think the important thing is to maintain a desire to someday make your dreams and aspirations a reality.

I remember seeing a photograph of the Magellan birdwing butterfly when I was a child and being so moved by its beauty. The description said that the yellow wings shined like pearls when they moved and I dreamed of seeing such a butterfly myself someday.

This butterfly can only be found in one area of Taiwan. I am now over 60 years of age, but I was finally able to travel there and see it in person. Even the famous anatomist Takeshi Yoro, who has loved insects since he was a child, didn’t start collecting and studying insects again until he was over 60 years old. The subject of your curiosity can be anything and if you continue to desire it, I believe all of us are capable of rediscovering ourselves.

(FIN)

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Part 1 of 2 》Shikohin: The Connection Between Logos and Physis. Interview with Biologist Shinichi Fukuoka