Shikohin is something that we consume that may not have any nutritional value or benefit in sustaining our bodies.

Even though it is not a necessity to sustain life, shikohin is enjoyed in various ways around the world.

Perhaps shikohin is rather a necessary part of what makes us human.

When contemplating shikohin, we must address the question of what is necessary for human life, and by extension, what defines humans as a living being.

For our new series, “To Live, To Relish,” we will explore what shikohin and its experiences means to us in our modern world, and interview leading researchers, anthropologists, historians, and more.

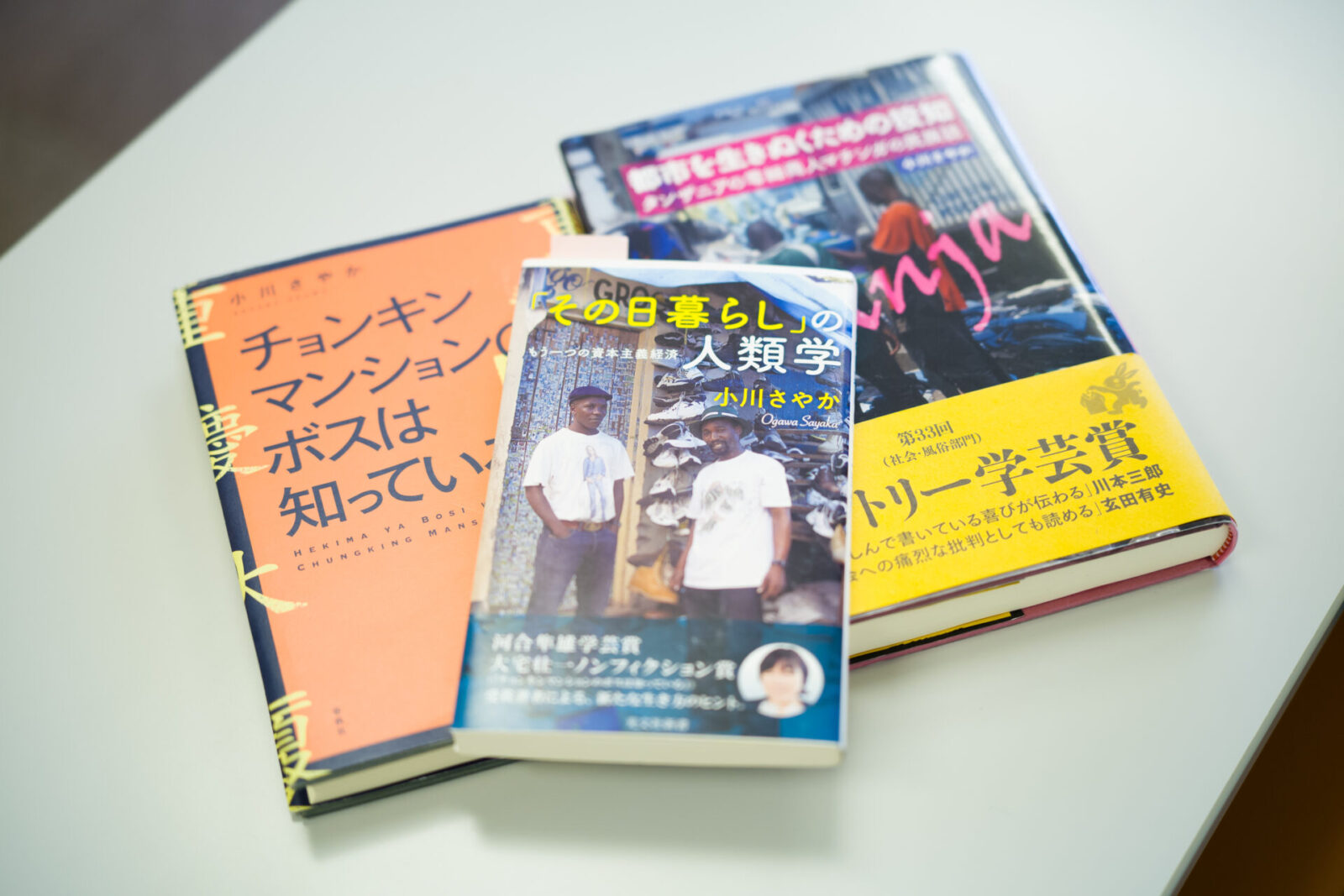

For this article, we interviewed cultural anthropologist Sayaka Ogawa, a researcher at Ritsumeikan University.

Ogawa specializes in African studies. While she was still a graduate school student in 2001, she went to Mwanza City in Tanzania to conduct participatory observation research. She has since studied the business customs and practices of petty traders called “machinga” and how they build their social relationships.

Participatory observation is a research method in which the researcher physically resides in the region they are studying for an extended period of time,observes and interviews subjects while living as a member of their society.

One area where Ogawa conducted interviews were street corners where people gathered for coffee and conversation called kijiweni. Kijiweni is a place for people of all ages, genders and walks of life to gather and share conversations over a cup of coffee. “This was the best place to conduct my fieldwork because people share their true thoughts and opinions which would never be shared in a formal interview setting,” says Ogawa.

In the kijiweni setting, which was filled with information that is invaluable for researchers, coffee played an important role.

In this article, we will dive into the world of coffee gatherings in Africa to explore how shikohin plays a role in equally connecting people and facilitating smooth communication.

Peddling used clothes for research

—— We heard that you travel alone to Tanzania and Hong Kong to conduct your research. I am very impressed by your courage to venture alone into a foreign land in this way.

This is a common method of conducting research in cultural anthropology called participant observation so there is nothing special or unique in what I am doing. In participatory observation, we conduct direct observation of a target society by residing there for an extended period of time and living life as a member of that society.

I began my research on street vendors in Tanzania in 2001 when I was a graduate student, and I spent a year and a half peddling used clothes on the streets and living among the locals.

—— I am surprised to hear that you worked as a peddler yourself. Was there any concern that your presence would influence the way your target subjects acted?

Of course there is always that concern. In fact, I believe I had a not-so-small impact on the local community.

In Tanzania, the job of peddling clothing was originally a man’s job, so when I first started doing it, it was very rare situation and people found it strange. However, my example led to an increase in the number of women peddlers.

Because of this concern of influencing the local community, it used to be said that cultural anthropologists should be like “kuroko” (stagehands that are dressed in all black in Japanese theater). However, there is some information that cannot be obtained by simply being a kuroko in the background. In recent years, there are more and more research papers that include and discuss what influences the researchers’ presence had on the local community.

Breaking down assumptions and broadening perspectives

—— Why did you choose Tanzania as your research target in the first place?

The reason is not very significant. When I was a student at Shinshu University, I became intrigued by cultural anthropology and I knew that it was what I wanted to study if I went on to graduate school. However, I had not yet decided what or where I wanted to study.

I joined the Wandervogel group at the university and realized that as long as I had my Kisling (a large backpack for mountain climbing), I could go anywhere. So just like many other university students, I backpacked and traveled around the world.

The reason I chose Africa as my target research region was simply an extension of my desire to travel from my university days, and I thought if I could go anywhere in the world, the further away the better. It was a coincidence that I ended up in Tanzania. For graduate school, I attended Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies and my advisor happened to be conducting research on rural economies in Tanzania.

Fieldwork requires a lot of preparation. Although it depends on the country, one may need to obtain a research permit or be accepted as a researcher at a local university. Choosing the same country as your advisor makes things easier because they already have experience doing fieldwork in the region and they have the personal contacts that are necessary to get the proper authorizations.

—— So Tanzania was an easy choice for you to choose for your research. What did you find so intriguing about cultural anthropology?

The reason I chose cultural anthropology is because I am the kind of person that feels trapped when I think too seriously about problems that are too close to home. Rather than getting to the bottom of problems that surround me on a personal level, I feel that comparing examples of how things are handled in other countries and cultures, and learning about different ways to approach problems to be much more exciting.

For example, if you look at how the Japanese family structure is becoming increasingly nuclear and the challenges that arise from it, it feels like a very serious problem. However, if you look around the world, you find that there are many other ways that people approach family structures such as polygamy and commuter marriages.

Some people may not be compatible with a certain social structure or certain social norms, but there is surely a world out there that is more compatible for them. By finding these different examples, you can change the assumptions you had on how things are supposed to be and broaden your perspective on different values. This way of thinking in cultural anthropology suited me.

My area of study is focused on economic anthropology which studies economical acts such as gift-giving, exchanges, ownership and money. One of the driving forces behind my research is my interest in finding economic principles that function in a completely different way from how we understand economic principles in Japan.

Don’t you think it would be fascinating to see a society that runs without money?

Ah, but today we are talking about shikohin.

Gift giving expands social circles

—— Do you have any tips on how to blend into the local community and extract valuable information?

In fact, that’s exactly where shikohin plays an important role. When I go on fieldwork, I always pack a suitcase full of items that I think the locals will enjoy and cigarettes are one such item. I think that if the occasion comes up and I can offer them a cigarette, they are more likely to open up to me so I always carry some with me.

I actually started enjoying smoking cigarettes after starting my research in Tanzania because the people there do not smoke a cigarette alone, but rather pass it around and share it. So when I offered a cigarette to someone, it would be passed around and come back to me as well, so I had no choice but to smoke. As I continued smoking with them, it became a habit of mine.

—— In Japan we also occasionally receive a cigarette from someone, but perhaps sharing a single cigarette is not so common.

Tanzania is a society that has a culture of sharing openly and casually.

For example, when you are walking down the street, a person will suddenly shout, “Give me a few smokes from your cigarette!” Then some stranger who happens to be walking nearby will actually offer them a few smokes from their cigarette.

This is also true for other things besides cigarettes. Most of my fieldwork was done in kijiweni gatherings spots, and here there was always some kind of casual giving and sharing of gifts.

—— What kind of place is a kijiweni exactly?

They are small spaces such as back alleys or the eaves of stores where people naturally congregate. When people gather, coffee vendors come by and everyone starts chatting away over coffee. Kijiweni is a kind of hangout and you can find such places all over the towns of Tanzania.

The coffee that is served there is a very simple coffee that is brewed by boiling water in a kettle over charcoal and it is very bitter. The cups are small, like the cups used for drinking Chinese tea. Having one cup is not enough so everyone usually drinks about ten cups. The coffee is sold for about 10 yen, so drinking ten cups still only costs 100 yen.

The interesting thing is that people don’t buy ten cups to drink on their own. If there are ten people gathered in the area, then one person will buy ten cups to treat each person there.

When the next person comes, someone else will buy everyone one cup of coffee. If there are less than ten people there and someone new joins, they will tell the vendor that there should be a couple cups leftover from the previous payment, the newcomer will get their cup of coffee, and so on.

As conversations continue in the gathering, the person who was treated to a cup of coffee will start having a good time so they buy the next round of coffee. In this way, strangers connect through small, casual gifts and the conversation and social circle continues to grow.

Honest thoughts only shared in street corners

—— What kind of conversations do you hear in kijiweni gatherings?

All kinds, really. People may talk about the soccer game, a pretty girl in the neighborhood or even consult on relationship issues. Then again, they may also suddenly start a debate on political issues.

People of all jobs, genders and ages gather in the group so the range of conversations are very wide and interesting.

I had a few favorite kijiweni spots that I went to. It was my routine to go to kijiwenis after finishing peddling for the day and join in the circle of conversations.

When a foreigner like me joins, I first get asked a lot of stereotypical questions like, “Can you do Kung Fu?” or “Is it true that Asians eat snakes?”

After visiting a few times, however, the members of the group start to recognize you even though the group is a little different each time. As I my visits became a regular occurance, I started to think that I should conduct my interviews at the kijiwenis.

Of course, I let them know that I was a researcher, but they did not change their demeanor and held their discussions in their usual manner so that was really great.

—— What did you ask about in your interviews at the kijiwenis?

I would ask a question such as, “What do you think about the increase in the use of electronic payment lately?” People would share their thoughts, such as how they think paying by cell phone has increased monetary relationships between people and that it makes helping each other out easier. Then someone would counter argue that the weight of money cannot be experienced in the same way by pushing a button and paying electronically, and so the debate will continue.

Ultimately, the group will start talking about deeper topics, such as what money really means for humans.

It is a great way to hear honest opinions and thoughts. There are times when the discussion gets so lively that it goes on past 11 p.m. at night.

Apart from the interviews I held at kijiwenis, I also conducted formal interviews.

For example, riots frequently occur in Tanzania so I asked people why they participate in them.

However, when I asked this question in a formal interview, they only gave me the standard answer, which is along the lines of “I am angry at the government’s violent way of handling things,” or “Although open air markets may be illegal, how do they expect citizens who do not earn enough to pay taxes to afford setting up a store in a public market?”

When I asked the same question in kijiwenis, I got more honest answers such as “There is no way we will win even if we fight the government, so rioting is our way of venting. We riot and get away before the police catch us, and that makes us feel better.”

Treating each other to coffee builds equal relationships

—— Do you think that coffee plays a role in bringing out honest thoughts of the people in the kijiwenis?

I think so. As I mentioned, one must first treat and be treated to a cup of coffee to join in the circle.

When we go out to bars with friends, we tend to only talk to our friends. At the kijiweni, people of all ages and genders who happen to be gathered there by chance form a circle of conversation and everyone joins in.

It is similar to cafes in Europe where the atmosphere is open to everyone. When you join a kijiweni, there is an understanding that everyone there is treated equally.

The human relationships in Tanzania are not as hierarchical as those in Japan. Of course, even in Tanzania there are some hierarchies, such as the boss in the workplace and doctors in society.

However, even if some great doctor comes and joins the group in the kijiweni, the other members speak honestly to them and may even share their opinion about how it’s unfair that doctors prioritize caring for people with more money.

I believe this atmosphere is created because everyone is sharing a drink or some food together. Because everyone is sharing the same thing, they are reaffirming their equality. At a kijiweni, everyone who participates simply becomes one member enjoying a cup of coffee regardless of age or status.

In terms of creating equal relationships between people, cigarettes act in the same way. Smoking alone does not create any connections with anyone, but sharing a smoke with the people around you creates a sense of camaraderie.

Part 2, “What if We Don’t Have to Return Borrowed Items Right Away?”

Photo: Saki Irimajiri

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Editor / Writer. A freelance editor. Born in Yokohama and based in Kyoto. Associate editor of the free magazine “Hankei 500m” and “Occhan -Obachan”. Interests include food, media and career education programs such as “Internships for Adults”. Hobby is paper cutting.

Editor and creator of the future through words. Former associate editor of Huffington Post Japan. Became independent after working for a publishing company and overseas news media. Assists in communications for corporates and various projects. Born in Gifu, loves cats.