Gardening has been a part of civilization in both Eastern and Western nations since ancient times.

Even today, gardening is still a part of daily life for many people. There are gardens ranging from those that are designed and tended to by professionals, to home and schoolyard gardens. Everyone has interacted with a garden at some point in their lives.

If you think about the concept of gardening, however, it is quite a mysterious practice.

In terms of life essentials, gardening exists outside the scope of food, shelter, and clothing, so it is not a necessity in our survival. Furthermore, in regions outside of the city, nature and greenery exists naturally without human intervention.

So why have humans chosen to create gardens, which are essentially a controlled state of nature?

This question resonated with DIG THE TEA’s exploration of human experiences that melt time, so we spoke with art philosopher Tomoki Yamauchi to get some answers.

Yamauchi has been working as a gardener since his university years, and is now a researcher on gardening theory which is based on his own experiences and field work.

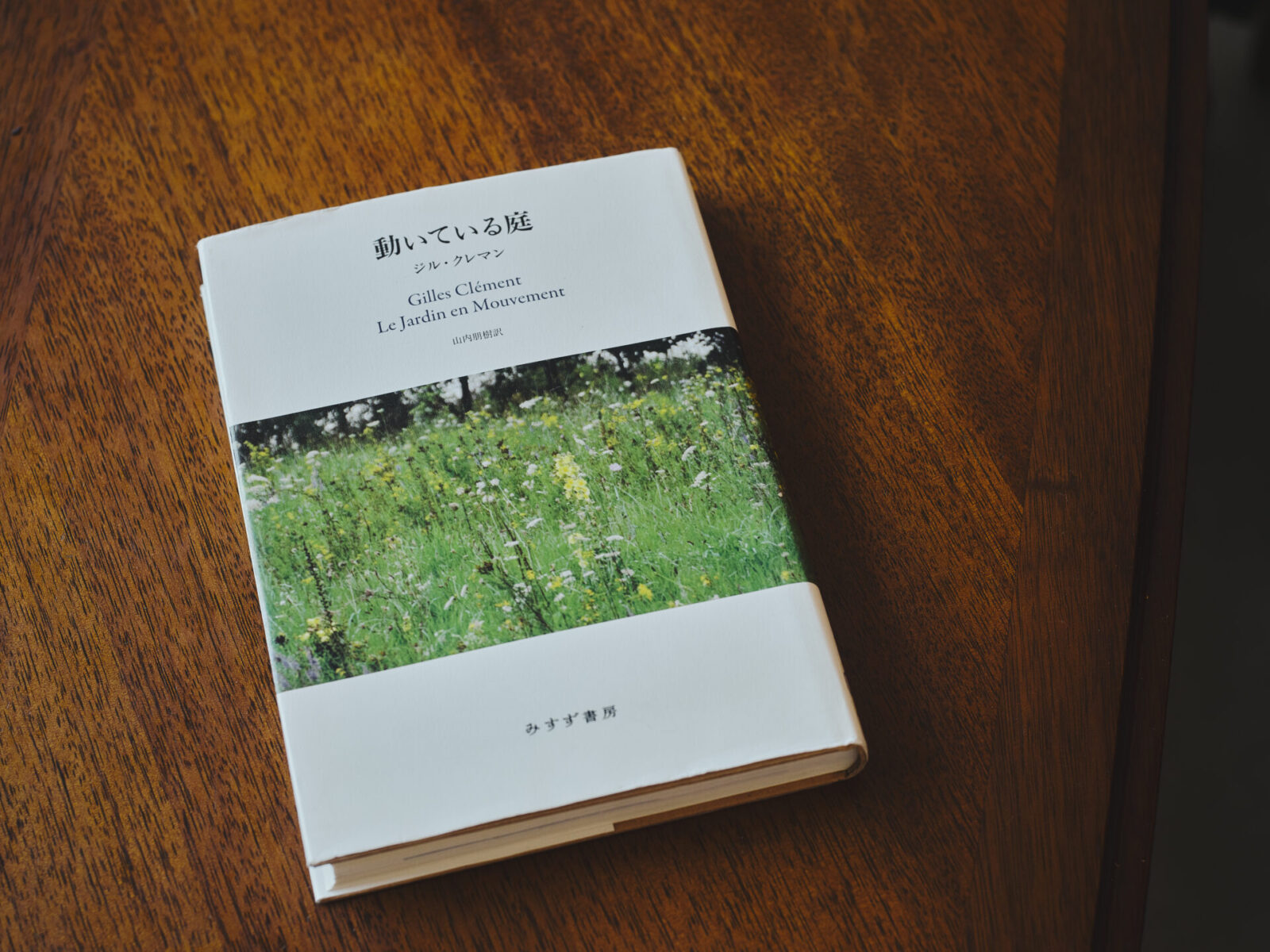

He has translated French gardener and philosopher Gilles Clément’s masterpiece “The Garden in Movement” (Misuzu Shobo, 2015), which has had a profound impact on the world of contemporary landscaping, and introduced this work to the Japanese audience. He also writes a series titled “Moments that Create a Garden” for an online web magazine Kaminotane. Currently, he is studying gardening form and ecology as a gardener while conducting field work at the Kannon-ji Temple in Fukuchiyama, Kyoto.

What do gardens really mean to humans? We visited Yamauchi at his research lab in Kyoto University of Education to find out.

(Text: Junya Shinohara, Photos: Eichi Tano, Interviewer/Editor: Masayuki Koike)

Back to basics, and studying what lies in the “shallow” part of garden

── You study gardens from the perspective of art philosophy. Does your work mean to interpret the ideas and philosophies of the creators behind the gardens?

I would say that such work was my main focus in the past. I translated and introduced the work of French gardener Gilles Clément and his book “The Garden in Movement” to Japan, which led to further work in writing and talking about his ideas.

However, one day I realized that I was not really able to describe what I saw in actual gardens, or weave together in words what was being expressed in those gardens.

This realization led me to start writing my regular series titled “Moments that Create a Garden” (Yamauchi’s book is scheduled to publish in late June 2023 under the same title by Filmart). In this series, I write in detail about the placement of objects in a garden. I think in depth about why the gardener chose to place rocks and plants where they did.

── In your series you tell your readers, “Take a thorough look at the garden!”

Yes, that was the first theme that came to mind when I started writing the series. When discussing gardens, I realized that, before studying the various pieces of information scattered throughout the garden and getting into its depths, it is more important to look deeply into the composition of the objects in front of you. In other words, one must start by examining the basics, or the most shallow part of the garden, first.

For example, when someone goes to an art museum and looks at a painting, they often take a brief look at it and then immediately turn their eyes to read the description. More recently, people use audio guides to explore museums. After they hear the name of the artist, date and commentary on the piece, they quickly move on to the next piece of work. They get a false sense of understanding about the piece, without hardly spending any time observing it.

Of course, I am not saying that there is no value in such experience. However, can we really say that this experience allowed a person to observe and appreciate the painting?

When an artist creates a painting, there are various possible patterns for how they go about their creation. For example, they may start with a rough sketch while building on the appearances of shapes in the whole piece and being inspired by the imbalance of light, dark and gradation. Or they may choose to add a certain color and then add another color to counteract with the dominant presence of that first color. In this way, artists work with very concrete and specific meaning and objectives. No matter what a painter is working on, they pay their utmost attention to what is going on in the complex field of forces that they are creating on their canvas.

I believe the same is true in gardens.

To give an example, there is a garden in Ryoan-ji Temple that is introduced in a book published in the late Edo Period (1799) that introduced famous gardens in Kyoto called Miyako Rinsen Meisho Zue. In the book, this garden is described as “Tora no ko watashi,” which means “a mother tiger leading cubs across a river.”

If the garden is called “Tora no ko watashi,” then the placement of the rocks must make us envision the scene of a mother tiger leading her tiger cubs across a river.

This means that when creating the garden, the gardener must think about what kind of rock to use, where to place it, how tall it should be and which way it should face. They must also look at the rock’s placement in relation to the other rocks and how to establish the garden as a whole. All of these are given thorough thought.

Gardeners really put in a lot of thought and make detailed adjustments when placing a rock in the garden. I wanted to describe in words the reality of the gardener’s work and such thought processes.

── I believe this must come from your background in working as both a gardener from a young age and in art philosophy research. You have experience in both on-site practices and ideologies.

Something I have felt while working both as a gardener and in research is that there is a discrepancy between the public perception of a garden and the gardener’s view.

There is a famous line in the popular Japanese TV police drama where they say, “All cases happen on-site!” and I felt that was also true with gardens (laughs).

2263 In addition to teaching art theory and art history, Yamauchi is also in charge of hands-on garden practice where students build their own gardens at Kyoto University of Education.

Art, philosophy, and part-time gardening

── Why did you start working as a gardener?

It was a coincidence and not something I put a lot of thought into.

While attending a university in Kyoto, I took a class on Japanese art and realized that even though I was living in Kyoto, I had not visited many temples and shrines.

I started visiting temples and shrines to study its various aspects such as the architecture, art work, and Buddhist statues. One especially caught my attention and they were the gardens.

Around the same time, I was taking a class on installation art and we were studying gardens. Through that class I met a master gardener and got acquainted with him. He was tending a garden belonging to Jakucho Setouchi, a famous Japanese Buddhist nun, so I asked him if I could see it. He told me he was working on it that day so let me come along.

When we arrived , the gardener quickly disappeared to give orders to the other workers. Although I was excited to be there and see the garden, once inside I found myself surrounded by busy gardeners working their jobs. One of them called out to me and asked, “What are you? A newcomer? Either way, come hold this for me.” So before I knew it I was helping them out. For some reason, the master gardener handed me a daily allowance at the end of the day and told me to come again (laughs).

The pay was not bad so I started working part-time with them after that.

── So while you were studying art and contemporary art philosophy, you worked part-time as a gardener?

Yes. I was an art major, and during my first year I painted works influenced by fauvist artist Matissed, but ultimately landed on art installations. As part of a broad definition of art installations, I began working part-time as a gardener. Nevertheless, I was always interested in literature and philosophy, so I gradually became interested in garden theory in addition to art and garden work.

I started reading more literature, interviews with literary figures and critic dialogues. I also read Akira Asada’s “Structure and Power,” which I found in the painting room. That book led to my interest in contemporary French ideology, and although I only had a shallow understanding of the genre, I attended Mr. Asada’s private seminar that was held at Kyoto University.

After I graduated university, I continued working in gardening and started my own business. However, my interest in art theory was growing so I decided to attend graduate school while working as a gardener. I studied under the supervision of Toshiaki Shinohara, who is known for his research on Henri Bergson and Gilles Deleuze, and his translation of the works of Umberto Eco. The class was like a seminar that was run by him and Atsushi Okada, who is known for translating works on Western art history and contemporary Italian ideology.

When I introduced myself in class as a gardener, everyone was always very surprised. They would ask me what I was doing there, or if my family runs a gardening business. Looking back, I think I was a strange student (laughs).

I studied French philosophers for a few years, and one of the upperclassmen who had returned from studying abroad in France introduced me to Gilles Clément. It was at that moment that my studies in theoretical research and gardening finally merged together.

Pansies, a symbol of resistance in the face of disaster

── What were your first impressions after reading Gilles Clément’s book for the first time? “The Garden in Movement,” which you later translated, talks about a “garden theory” that focuses on the movement of plants which changes the shape of the garden itself.

Because I was working as a gardener, I understood the sensation of plants moving in the garden.

No matter how much you tend to a garden, there will be moss and ferns that spread out and Sarcandra Glabra and Ardisia Crenata that come out from new places. New plants come out from pores that were carried in by the wind or seeds that were dropped by birds. Gardeners work every year to reduce and organize these plants, or grow them out and tend to them year after year.

However, I was never very conscious of this fact.

Clément had elevated the methodology of garden care into a principle of garden creation. Because of this, the concepts introduced in “The Garden in Movement” came as a big shock to me.

From there, I was also influenced by one of his core concepts of the third landscape.

── What is the third landscape?

Clément refers to areas that humans do not enter, such as vacant or abandoned lots or the land beside railroad tracks, as third landscapes. In cities that become increasingly urbanized, third landscapes are where one can find a diversity of flora and fauna. He considered these spaces to be the equivalent of nature reserves.

Clément gave these places a new definition and looked at them in a more positive light. He proposed that these are “places of resistance” in the ever-expanding cityscapes.

However, Japan faces the problem of an ever growing number of vacant houses and properties because of the aging and declining population. Every corner of the country is turning into third landscapes.

The Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident added fuel to fire as it created massive third landscapes that were inaccessible to humans.

I began to think that the potential in the late-20th century invention “places of resistance” was coming to an end.

However, it was at this time that I began taking notice of pansies.

── Pansies, as in the flowers that are often planted in planter boxes on porches?

That’s right. In the spring of 2018, I was given the opportunity to do fieldwork in Namie Town of Fukushima Prefecture, which was an exclusion zone until just prior to my visit. For someone like myself who is always interested in and studying plants, I could envision what a place that has been deserted will look like before I get there. I assumed it would be filled with areas like the third landscape.

However, the moment I got off the train at the station, I noticed that there were pansies in full bloom in planter boxes lined up along the road. Even though much of the area around the train station was deserted and empty, there were pansies lined up and blooming in the newly reopened station, the city hall and nearby ramen shop.

This was completely unexpected and felt there is a symbolic meaning to this.

Pansies and flowers growing in planter boxes need to be watered daily or they will wilt. This meant that there were not only people who planted and arranged the planter boxes of pansies, but also people who were continually coming to this region to water them. In other words, people were doing gardening work.

Even though very few people had actually returned to live in the region, the pansies seemed to signify that there were indeed people living in that region and they were waiting to welcome others.

This act of planting pansies in such a dire situation and continuing to do gardening work seemed to express the people’s earnest desire to bring back regularity in their surroundings.

Until then I never really understood the appeal of pansies, but when I saw them in this landscape, the way I understood the flowers changed completely. Because of my preconceived assumptions on what the landscape would look like, the presentation of these pansies left a huge impression on me.

(Editor’s note: The results of Yamauchi’s field work are summarized in his article, “Why there are pansies, rather than nothing, in the reconstruction of Namie Town”, published in the magazine “Arguments #3.”)

At its essence, there is “variation”

──Perhaps spaces where people plant pansies can also be included in the wide definition of a garden. What do you believe the definition of a garden is?

That’s difficult to say. I think if you define something, you are reducing it to only its fundamental essence and that takes away from the richness of gardens.

If you put it very simply, Japanese gardens are characterized by its ishigumi, or the placements of rocks.

In the west, even gardens designed around rocks simply scattered them on the ground. In Japanese gardens, the rocks are deliberately buried in the ground to emphasize the standing form of the rocks and their relationship to their surroundings. It is designed to make it seem as if the bedrock underground has been exposed.

Nevertheless, if you define Japanese gardens as simply a garden that has ishigumi, that would exclude a garden with rock stairs or stepping stones from the definition. It would also exclude gardens with only plants from the definition of a Japanese garden. However, if we define gardens as something that simply uses plants, it doesn’t match with our image of a so-called Japanese garden either.

That is the difficulty of defining what constitutes a garden.

── Gardens are also used to describe places like schoolyards and playgrounds.

That’s true. In fact, “niwa,” which is the word for “garden” in Japanese, illustrates a flat space that exists between buildings. At properties in the countryside, there is a space in between the main house and the storage hut where people usually park their cars. That space is also called a “niwa.” There are also gardens of fruit trees and flowers such as orchards or plum groves.

Furthermore, the word garden is used in various analogies and metaphors in our world today. You can find the word garden being used in shopping malls, hotels, small plaza and even in the name of commercial products.

Really you can say it can be used anywhere now (laughs).

A garden is a truly expansive concept and I feel that its essence is in its variation. I think this variation is very important.

── You mean to say that the concept of what constitutes a garden is various and ever-changing.

Yes. For example, gardens in Japan include places that are meant for leisure, but also places that are used for religious purposes and are considered pure.

In the Edo period (1603-1868) for instance, a garden called chisen kaiyushiki teien (a garden with a spring water pond) was very popular. These gardens were designed so you could walk through the pond or a small island. In the Heian period (794-1185), there were tsuriden (fishing pavilions) where people could fish or enjoy drinks on a boat.

In tea gardens and open air gardens, there were stepping stones placed among large evergreen trees to give the impression of walking deep into the mountains.

Gardens in the Heian period also had areas near the buildings where white sand was put in place for ceremonies and kagura (Shinto music and dance) performances. The white sand signified that this space was pure and sacred.

These spaces had religious significance. The same is true for the Southern Hojo garden at the Zen temple and the karesansui (dry landscape garden) that eventually developed as well.

Gardening as a method of expressing control

── Would you agree that variation and expansive definitions are the essence of gardens?

No, it is still possible to add more to what is considered the essence of gardens (laughs).

For example, if we look at it in relation to nature, then control is also an important element.

It is often said that eastern cultures follow the course of nature while western cultures control the course of nature. However, the act of following and controlling the course of nature are simply two sides of the same thing.

I think you will understand this better if you think about the process of craft.

In ceramics, for example, one must understand and follow the characteristics of clay in order to properly transform it into a desired shape. If you look at this from the opposite perspective, it is the same as learning how to control the clay.

── In that sense, even though eastern gardens are known for following nature, you mean to say that in fact it is also controlling nature?

Japanese gardens are thoroughly controlled and managed.

Take a single pine tree for example. You often see twisted trunks and branches in gardens, and this was originally inspired by pine trees along coastal areas that became distorted and broken by strong ocean winds.

It takes a lot of manpower in order to reproduce that look.

If left alone, a pine tree will grow straight up, so in order to create the desired look the buds and leaves are plucked, the branches are pruned, and sometimes the shape of the tree is warped by hand.

By contrast, take the western gardens of the Palace of Versailles for example. At first glance it appears to be under extreme control and management by human hands, but upon closer look, you will find a wide variety of plants and animals in the bosquets along the waterways and on the outskirts of the garden.

Even if it appears to be following the course of nature, it is in fact controlled, and even if it appears to be controlled, it is following the course of nature. By simply changing your perspective, the result is inverted.

── It’s true that we wouldn’t look into the wilderness that is not controlled and call it a garden.

An important part of garden-making is determining at which point during its transition from a deserted land to an arboreal forest (a forest where the plants have stabilized and are no longer changing) it becomes a garden. In other words, it is about the extent of control within that transition.

In the ideal progression of plant transition, there will first be rocks and sand, and then lichens and moss and robust grasses that grow on the rocks themselves. Eventually, soil begins to form and more grasses and pioneer trees begin to grow. More trees will then grow, and as this continues to repeat itself, the area turns into an arboreal forest.

In terms of garden-making, the first stage is the karesansui (dry landscape). When moss starts to grow, it is like the moss garden in Saiho-ji Temple. Then we have gardens with grass and flowers, and then the gardens that make you envision pine trees on the coast. Some gardens will seem like a forest.

In any case, the question is the degree of control that is put into the garden to keep it within a certain point of the natural transition.

── Nonetheless, as long as it is a part of nature, we cannot fully control it. Is such ambiguity also part of the essence of a garden?

Clément’s “The Garden in Movement” is controlled in the sense that it creates spaces for humans to enter, but essentially the plants spread out their seeds and determine where they will settle first.

The gardener carefully observes this distribution and mows the grass in order to preserve the space for the plants. Therefore, the plants choose how they will shape the area, and the gardener makes adjustments to conform to that shape.

They conform, but also control. They let it go wild, but manage it at the same time. Even here, the degree of control is what is important.

Humans of always sought gardens of paradise

── Humans have been creating gardens despite the fact that we cannot attain complete control. Do you think that, because humans are living in a natural world or in a society that is largely out of their control, we develop a desire to gain control over something, even if only on a small scale?

If you look back into human history, mankind has always been in pursuit of a kind of paradise garden, at least in certain regions of Eurasia.

There is an ancient Chinese geography book called Shanhai Jing (The Classic of Mountains and Seas), and in that book there is an island out in the sea called Horai

where it was said that immortals lived and that they had medicine for immortality. This island became the first motif for the Oriental garden.

In Western Asia, where there are many desert regions, their version of paradise includes a lot of water and fruit trees in their gardens. In areas influeced by Christian culture,their paradise garden was represented by the image of the Garden of Eden.

A paradise garden is one that is isolated from the outside world that has something that is beneficial for humans. Each region and generation has a different image of the ideal natural world, and I think that is demonstrated in how they create their paradise gardens.

── Perhaps the garden was a place where people could project their ideal image of the natural world. I feel that the act of creating a garden in a space within one’s reach and control is a form of self-care.

If we were to expand the discussion to house plants, bonsai and other ways of growing plants outside of the garden, I’m sure there would be a significant number of people who are interested in caring for plants.

That desire extends to our desire of wanting to keep a pet. Even though we may think it is a hassle to water our plants every day, we do it anyway (laughs).

Plants are the same as pets in the sense that they demand a lot from us. Of course, life may be easier without these things because they are not necessary for our survival.

Still, for some reason humans desire to keep such time-consuming things close at hand. Although it may seem like a contradiction, on one hand human beings have the desire to live an easy life on their own, but at the same time they desire to have multiple things to take care of.

── At a glance, they are not a necessity in terms of our survival, but we choose to create gardens anyway. In that sense, it is similar to shikohin like tea or alcohol.

That’s very true. In fact, I love coffee, tea, cigarettes and all types of alcohol. I am a fan of all types of shikohin (laughs).

When people criticize shikohin, they often say it is something we can live without. Like, do we really need it to survive? However, I think this question in itself is problematic.

Our culture as a whole is like shikohin.

We do not wander around half-naked in order to only wear the bare minimum of what is required to protect our bodies. We do not eat meat by directly biting into the flesh of an animal. We are always adding various excessive aspects into our lives.

This excessiveness is in some ways extreme, and we enjoy our clothing and food by continuously indulging in excess things that are not necessary for our survival, even if they are poisonous at times. In other words, we are increasing the varieties of shikohin at an insane rate, to the point where we are losing sight of the very essence of what we are doing.

The same is true for gardens. As humans have pursued a paradise garden that is unrelated to survival itself, humans have continued to pursue more excess and that is how we have cultivated our gardens. If we define the essence too clearly, perhaps the history of gardens could be described on a single page (laughs).

I strongly believe that it is the things that are considered shikohin that make up the very essence of our lives and livelihood. That is the only possible explanation.

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Born in 1990, Nagasaki. Freelance writer. Interviews and writes about book authors and other cultural figures. Recent hobby is to watch capybara videos on the Internet.

Editor, Writer, etc., for PLANETS, designing, De-Silo, MIMIGURI, and various other media.