It goes without saying that shikohin represents a wide variety of things.

Everything from the product itself to how it is made and enjoyed, and the region and culture around it is largely diverse. It is not an overstatement to say that there are as many types of shikohin as there are ways of ife.

On the other hand, shikohin often has no nutritional purpose, so they exist more out of a “want” than “need”.

While shikohin is diverse and not a necessity for life at first glance, what then is its purpose in human livelihood?

Toshiaki Ishikura, a researcher of mythology and anthropology of art, says that shikohin is livelihood itself and the vernacularization of it is also an act of resistance in itself.

Ishikura has conducted fieldwork all over Japan and the world, with a focus on India, Nepal and the Tohoku region. He researches mythology, with a focus on the “mountain gods” of various regions.

Ishikura collaborates with artists to create art pieces while also researching the anthropology of art, which is the exploration of human beings beyond cultural and biological boundaries. In 2019 he collaborated with artists, architects, and composers to create and exhibit “Cosmo- Eggs” for the Japanese pavilion at the 58th La Biennale di Venezia.

How can we understand shikohin through the perspective of mythology and anthropology of art?

In Part 1 of this article, we discussed the relationship between shikohin, nature and culture. In Part 2, we will dive into the essence of shikohin and human livelihood. Under the keyword, vernacularization, we will discuss the future of shikohin.

#Series “To Live, To Relish”

For our series, “To Live, To Relish,” we will explore what shikohin and its experiences mean to us in our modern world, and interview leading researchers, anthropologists, historians, and more.

Shikohin is something that we consume that may not have any nutritional value or benefit in sustaining our bodies.

Even though it is not a necessity to sustain life, shikohin is enjoyed in various ways around the world.

Perhaps shikohin is rather a necessary part of what makes us human.

We cannot separate human “needs” and “wants”

── In Part 1 of this interview, you made the point that shikohin are embedded in the nature and culture of each region around the world. On the other hand, shikohin is often understood as something that is not nutritionally necessary and therefore as something “extra” that we can live without.

Looking back to my days doing my fieldwork, I believe one thing I learned is that we should not separate “needs” and “wants”.

We are living in a world that is overflowing with material goods and I believe it has made us develop a habit of separating “necessities for life” and “things that are extra.”

For example, without realizing it we have been led to believe that studying and working is necessary while playing is not. Things like shikohin, hobbies, festivals and leisure time are “wants” and not “needs.” In other words, they are treated as “unnecessary.”

However, in places where work and play are not separated, “needs” and “wants” have more diverse outlets and paths that connect the human body to society in the environment that surrounds them.

Perhaps there are a lot of people in Japan who have the understanding that we should work from 9 to 5 and enjoy leisure time and activities after. On the other hand, people working in plantations or driving buses and cabs in India will be chewing betel nut palm (a member of the coconut family which is commonly chewed like chewing tobacco in tropical Asian countries) while they work.

── So the idea to separate “necessities of life” and “wants of life” is not necessarily universal?

The potential of desire that humans possess is tremendous.

For example, when children are left alone they will begin to play on their own. Adults may think that playtime is not necessary, but for children play is the coming together of “needs” and “wants” and the very meaning of being alive.

We do not spend every moment of our lives doing only things that are necessary. We have moments where we are simply spaced out, relaxed or doing nothing. All these things, including resting, is part of being alive.

In the same way, shikohin has always been used as a way to ease our minds and rest our bodies. For children, sometimes having sweets is more important than having a meal.

Shikohin that brings “Well-Becoming”

── So enjoying shikohin is the coming together of “needs” and “wants” and essentially what it is to be alive.

In addition to being alive, there is also an aspect of shikohin that “makes them most of things” in life.

It leads to creating a deeper dimension in our daily lives. It allows us to make the most of the nature around us and take pleasure in its flavors. It turns moments of boredom into time for fun.

It is about living one’s life and to make the most of what we have available in our given environment. This also is directly related to the practice of arts and crafts.

When making the most of things incorporated into our lives, we find our world of “needs” and “wants.”

── So shikohin is something that is inseparable from life because it is “living and making the most of life”?

There is a movement called “lifestyle crafts” that is growing in recent years and many artists and craftsmen are creating beautiful objects that can be used in everyday life.

People are also rediscovering the appeal of folk crafts, farming, Akita’s matagi hunting and the culture of indigenous Ainu people.

These people believe that what is important is not only the world in which they live, but whether or not they are making the most of life and living in a way that they can truly feel alive. They are creating new realities not only for their own lives, but also connecting with others through material things and energy.

In other words, they are designing a new world through new relationships with people and material things.

In order to survive in this complex society that we live in today, there is a need for us to connect and pass on such wisdom.

The term “well-being” is often talked about in recent years and it is about how to live a better life. However, I think that “well-becoming” or being able to better change and adjust with other people will become more important.

In the midst of such big transformations, the question is how we can listen to (and become aware) of our inner desires and manifest those desires. I think that is what will be required of shikohin in the future.

The underprivileged people have vernacularized shikohin

── From what you have told us, I can see how shikohin is inseparable from the very essence of human livelihood.

Shikohin is also meant to simply be enjoyed and relished. Although an important point is that it is not something that is simply enjoyed without some kind of preparation.

Whether it is to smoke cigarettes or drink alcohol, it is necessary to have knowledge and manners in order to enjoy them in moderation without harming our health.

Medicine and poison are fundamentally the same thing, so it is a matter of discerning and mastering their use. I believe that this skill for living is a universal art that is common all around the world.

I think in the future it will become even more important and necessary to take a serious look at our tastes and enjoyment and explore them deeper.

Shikohin that has been taken rather lightly in the past often comes from rituals and customs of indigenous peoples. Rather than separating these shikohin from their roots, there is a lot of wisdom that we can learn from the “living arts” and the connections to the natural world that comes from these customs.

I think this will allow us to see why human culture has developed with such rich diversity.

── Diversity of human culture?

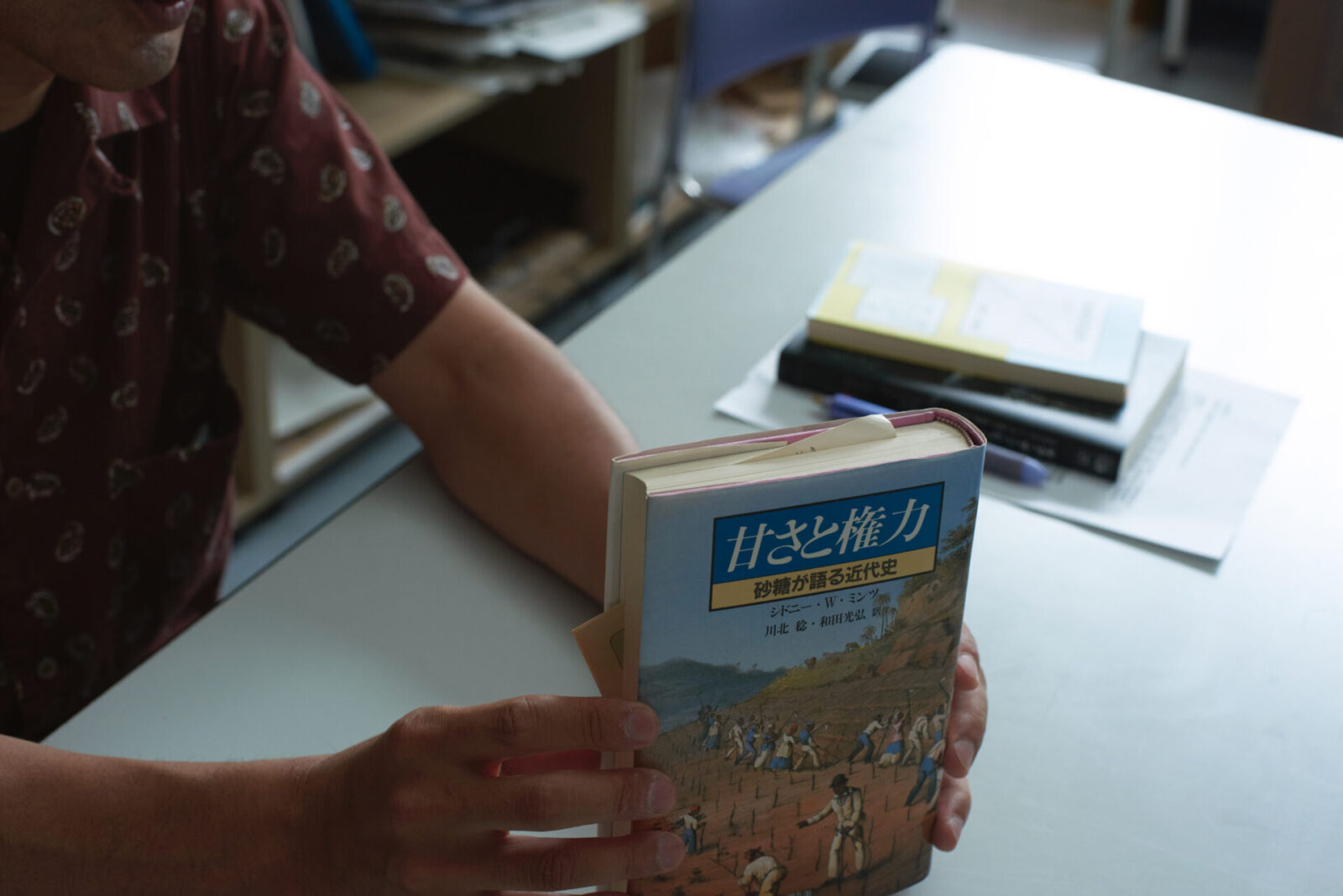

Shikohin were originally things that were found in the natural environment of the land people lived in. However, from a certain point shikohin began to circulate the world as a commercial product.

The first of such examples were sugar and tea. In colonial history, a system was implemented where the oppressed people were made to grow sugarcanes or beets and export them to the ruling countries. These products were often addictive or highly enjoyable so it was very profitable.

In other words, shikohin of the past were directly tied to colonialism and Western-centrism. Children who were growing the cocoa beans never ate chocolate, the people who grew coffee beans never drank coffee, and the people who cultivated sugarcanes and beets never enjoyed the benefits of sugar.

However, as I mentioned in Part 1, the people of Darjeeling who I studied in my fieldwork, have vernacularized such shikohin that was historically deeply connected to capitalism and colonialism. They took black tea which was originally being produced for England, and created their own culture and original ways of enjoying it.

Rather than drowning in the circuits of colonialism and capitalism and only experiencing deprivation, they found various methods and outlets for their own desires and redesigned the shikohin. In a broad sense, I think this was a movement for decolonization.

── Would you say that there was an important connection between shikohin and decolonization?

Both have a profound connection to people’s body and mind.

The desire towards creating their own pleasures certainly existed in people who lived in deprivation. I believe that hints to what shikohin will mean in the future can be found in the shikohin developed by these underprivileged groups rather than by the rich and privileged groups.

── What do you mean by that?

For example, people were deprived of attending live musical performances during the coronavirus pandemic. The first thing that people in power claimed as “non-essential” and eliminated was the arts and leisure activities.

I myself love music and if you asked me who the creators of modern day popular music are, it is the people who were made to cultivate the shikohin products such as sugarcane and coffee.

In the United States, it was the black workers in plantations that created the blues, a form of music that is rooted in the harsh life and working conditions of cotton fields. Another example is gospel music, which came from the gatherings in churches which happened on Sundays, their only day off. From there, jazz, rock and various forms of popular music was born.

When you think about it, the music we enjoy today is not rooted in excess. They were not created by those whose lives were sufficiently satisfied or luxurious, but rather, they came from people who were deprived. These were the people who needed shikohin.

This is why I think it is necessary for us to seriously look into shikohin and the culture and arts that surround them.

Shikohin connects us to invisible worlds and transcends the boundaries of the body and mind

── On the other hand, the social stigmas that surround alcohol, tobacco and caffeine are changing quite drastically today. It seems that traditional shikohin are undergoing major changes around the world.

For the future, I believe it is important for people to vernacularize shikohin and culture in ways that are enjoyable for themselves.

Speaking of which, there is an interesting movement happening in Akita, where I live now.

There is a brewery called Aramasa which used to make commercial sake that has started rice farming to grow their own rice. Another craft sake brewery called Ine to Agave Brewery was also established in Oga City to challenge the legal restrictions that don’t allow the creation of new breweries.

In another project, five breweries called NEXT5 have joined hands to share fermentation technologies and will produce sake together. They also organize sake events where DJs are invited to perform. For people who don’t drink sake, they offer locally roasted coffee and sweets made with figs and apples.

These new movements surrounding shikohin are playing the role of connecting old cultures and festivals to new lifestyles and culture. There are many such movements in Akita that are updating the local living arts and crafts and taking them to the next level.

The rural areas of Tohoku such as Akita were regarded as poor regions in the past where people would send rice, sake, women and soldiers to the city to survive. However, that is not true today.

We are moving away from the past realities where the rich and the poor and the oppressors and the oppressed were divided and into a world where people are more intertwined and able to design their own enjoyments in life.

I believe a new attitude toward shikohin will come out of these new changes in how people create their worlds.

──Do you think that the vernacularized shikohin that are created in these various regions will make the world a richer place?

As more people move to the countryside I believe that we are entering a new phase where the richness and diversity of country living will be seriously questioned.

I once participated in a festival in Tohoku and there was a moment that changed my view on everyday life and the world became much more colorful to me. For example, there are festive foods that are only eaten during certain festivals such as Kasube-ni (a dish made with boiled dried stingray). When you come in contact with such a shikohin, you get a sense that the temporal and spatial codes within you change.

The value of shikohin goes beyond simple consumption of a commodity. Shikohin allows us to experience a sense of “shifting gears” which connects us to invisible worlds.

It adds extraordinary experiences in our ordinary lives, or it creates major shifts in our senses, such as the change I experienced when my entire sense of reality changed at the festival. That is the role of shikohin.

── Will shikohin bring about “shift changes” in each region and local practices?

Shikohin also connects us in ways that surpass the boundaries of individual bodies and minds.

For example, I once experienced yamabushi training (mountain ascetics). After going through the training of walking through the sacred mountains on an empty stomach and being hit by waterfalls, we were all given a special meal and drink to celebrate the end of our training.

It was great fun to eat and drink together with everyone, passing sake around in large mugs, just as it has been enjoyed since ancient times. I think the feeling of giving and taking creates a comforting emotion that goes beyond our personal bodies and spirit.

Drinking tea with others, smoking shisha together, or drinking sake in a group while passing around the same cup are all such experiences. During Obon we gather around to watch the bonfire while drinking beer together. The children drink juice and experience festive activities. The elderly gather round for a cup of tea and engage in conversation.

These moments require a mediating product and that is where shikohin is most effective.

It is about sharing leisure time and relaxing together. I think that will be the value that we will rediscover in shikohin as we reconstruct what it means to create a plentiful and sufficient culture for the future.

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Graduated from International Christian University (ICU), majoring in political thought, and worked as an IT consultant, PdM for agricultural robots, and PjM for construction DX before going independent. His areas of interest include the humanities in general, agriculture, architecture, and publishing.

Editor, Writer, etc., for PLANETS, designing, De-Silo, MIMIGURI, and various other media.