“This is an Angelica acutiloba. Try smelling it.”

I brought the long and thin plant root that was pulled out of the medicinal plant garden up to my nose. It had a celery-like scent, yet much more potent.

“There aren’t many places where you can smell freshly harvested Angelica acutiloba plants. It has a very powerful scent that leaves a big impression. The medicinal plant known as Touki is actually the root of this plant after it is dried. We roast it and drink it as tea. It can be mixed with other tea, and in Korea, they add it to a dish called samgyetang, or a chicken ginseng soup.”

Yasushi Ogawa is the only person in Japan who is a licensed doctor in Tibetan medicine, also known as “amuchi.”

What kind of effects do these plants have on our health?

“Touki helps to expand your blood vessels and really warms up the body. Medicinal plants have various effects, but if you were to compare it to baseball, this plant would definitely be a major league player.”

However, Ogawa shares that, because Touki is officially recognized as a medicinal product, one cannot sell or buy it without a proper license. “If I were to sell this plant as ‘medicine,’ I would be arrested for violating the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law. If I were to cook it and sell it as ‘medicinal cuisine,’ it would also be against the law. However, it is not illegal for me to privately grow the plant.”

One can grow the plant but not sell it?

Ogawa smiles as he explains, “I found it sold at a local farmers market once. It is okay to sell it as a “‘plant’.’ It is also okay to grow them and eat them privately.”

Teaching through the body’s senses

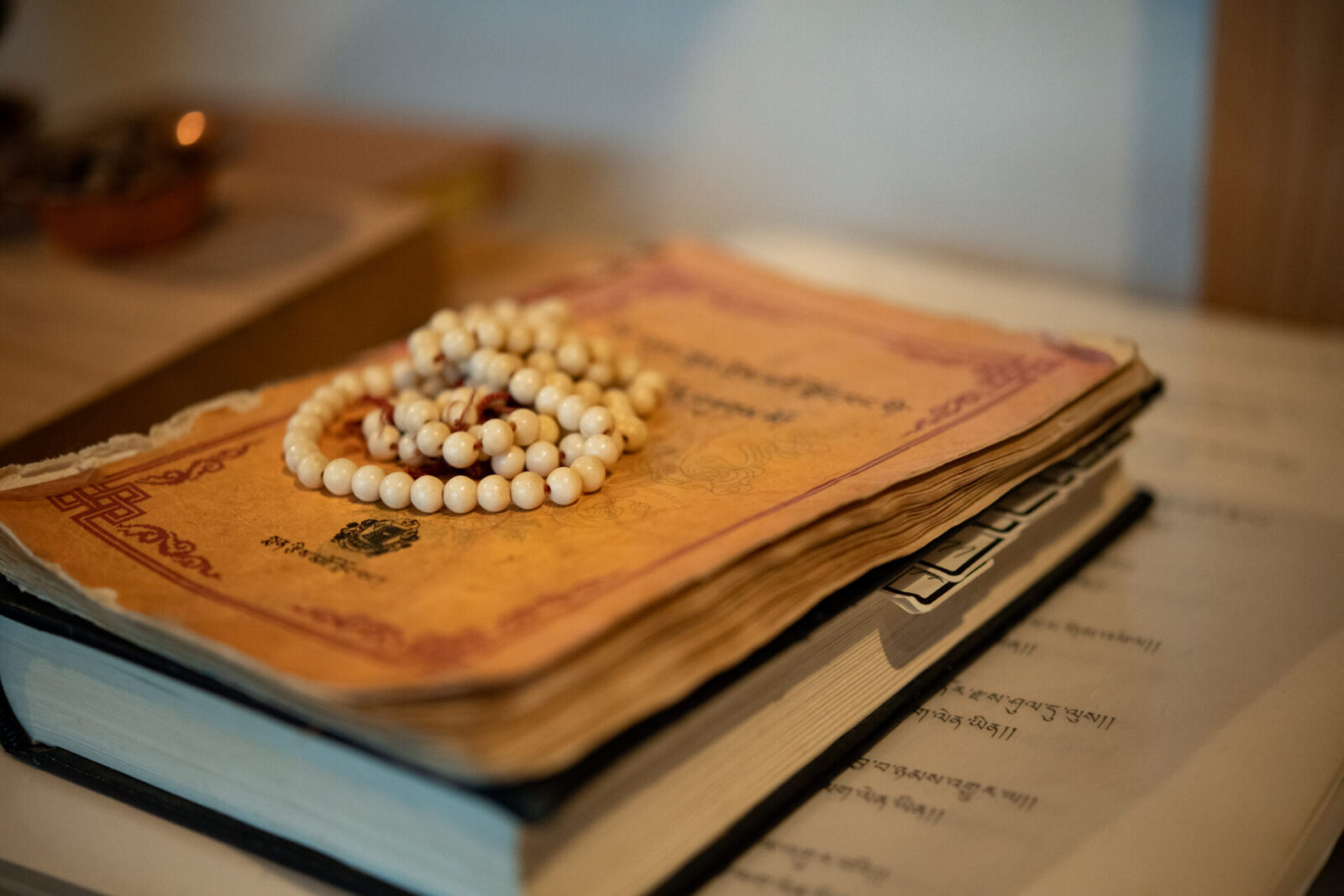

After graduating from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Tohoku University in 2001, Ogawa became the first person outside of Tibet to be accepted into Men-Tsee-Khang (Tibetan Medical and Astro-Science Institute) where he studied Tibetan medicine for six years and got his license as a Tibetan doctor (amuchi).

Tibetan medicine is known as one of the four great Oriental medicines, along with traditional Chinese, Indian, and Islamic medicine. Amuchi treats patients by examining their pulse and urine. They identify and collect medicinal herbs and prepare medicines themselves. Ogawa is the only amuchi in Japan and he is a master herbalist who is an expert in over 200 types of medicinal herbs.

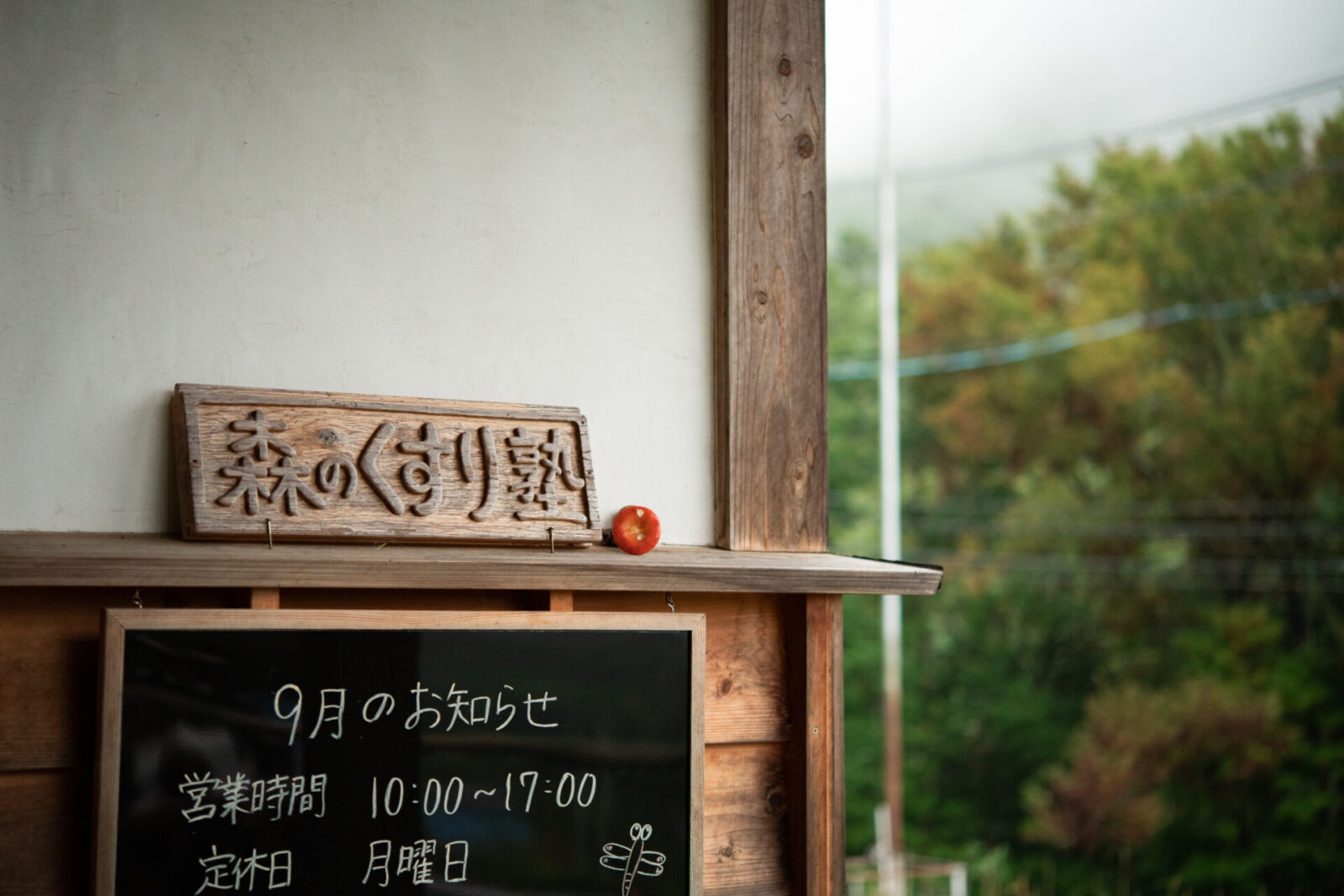

Ogawa runs a medicinal center called “Mori no Kusuri Juku (Forest Medicine School)” (Forest Medicine School) in a village about a 10-minute drive from Bessho Hot Springs in Nagano, which has been prosperous since the Heian period (794-1185) and is also known as the “Kamakura of Shinshu.”

In the medicinal herb garden of his center, there are other plants besides the Touki plant, such as the purple beech, an endangered wild species, and known for its anti-inflammatory and skin regenerating properties, and the yellow oak tree, which has long been valued as a gastrointestinal medicine.

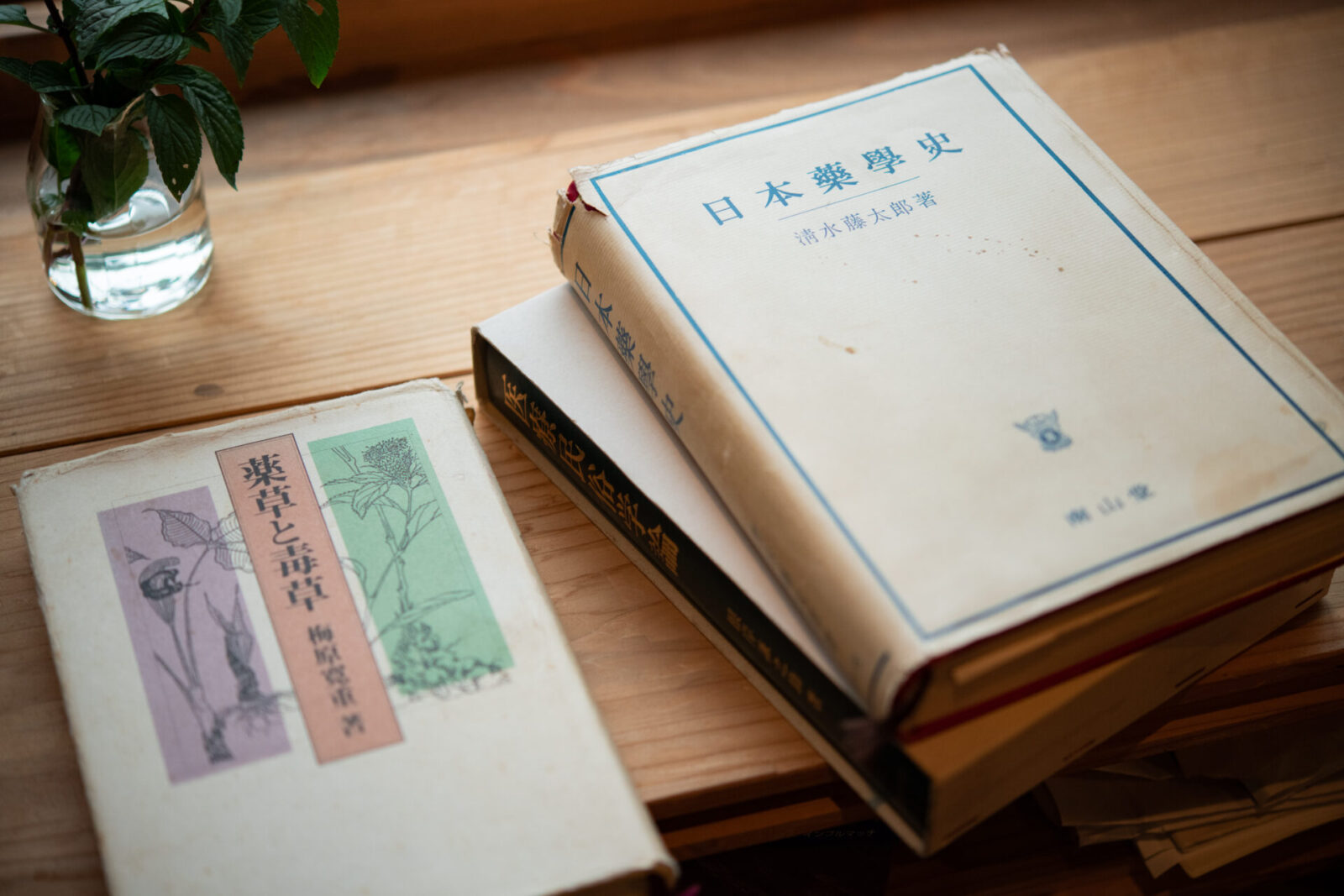

Ogawa’s business is not to roast and sell these medicinal herbs. He is using his knowledge and experience as an amuchi to research and preserve the practice of traditional Japanese medicinal herbs–-a practice that gradually lost popularity in postwar Japan during the period of economic growth and introduction of western capitalism and medicine. The practice of Japanese medicinal herbs is now in danger of disappearing.

He holds various workshops where he takes participants on walks in the mountains to use their body’s senses to find and learn about the medicinal plants they collect. He aims to help participants develop an eye to look at things from a different perspective. He says he was inspired by the Matsushita Village School. a private school that was opened by Yoshida Shoin in the Edo period.

Ogawa did not originally have such high aspirations whilst on his journey to becoming an amuchi. The reason Ogawa found himself in Tibet was mostly by chance. We will introduce his journey in this article.

The journey to Tibet

“I was always good at chemistry and science, and I wanted to get a degree in pharmaceutical studies.” Ogawa says he got into the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences of Tohoku University, but he became so absorbed in the archery club that he did not go on to search for a job in the field.

He worked odd jobs after graduation. He worked on a farm from 5 a.m. to 10 a.m., and then we would work at a drugstore from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. One day, he found a book on Tibetan medicine at a bookshop.

He had seen “Tibetan Book of the Dead,” a documentary supervised by religious scholar Shinichi Nakazawa, and he became interested in Tibet and Tibetan medicine. In 1991, he quit his job and traveled to Dharamsala, India, where the exiled Tibetan government was located.

This was before internet connection was popular, and he recalls that the life and cityscape of Dharamsala was much like Japan in the 1950s. He fell in love with the atmosphere and began studying the Tibetan language.

He enjoyed it so much that after returning to Japan three months later, he continued to visit Dharamsala where he studied for two and a half years. As a result of his hard work, he was accepted into “Men-Tsee-Khang (Tibetan Medical and Astro-Science Institute),” which is known as the most prestigious school in Tibet. In March 2002, he became a student of Men-Tsee-Khang.

The Tibetan medical school’s “unique” curriculum

Men-Tsee-Khang has a very unique curriculum. There is a preparation period of one year and another six years of studying traditional medicine with a class of 25 other students.

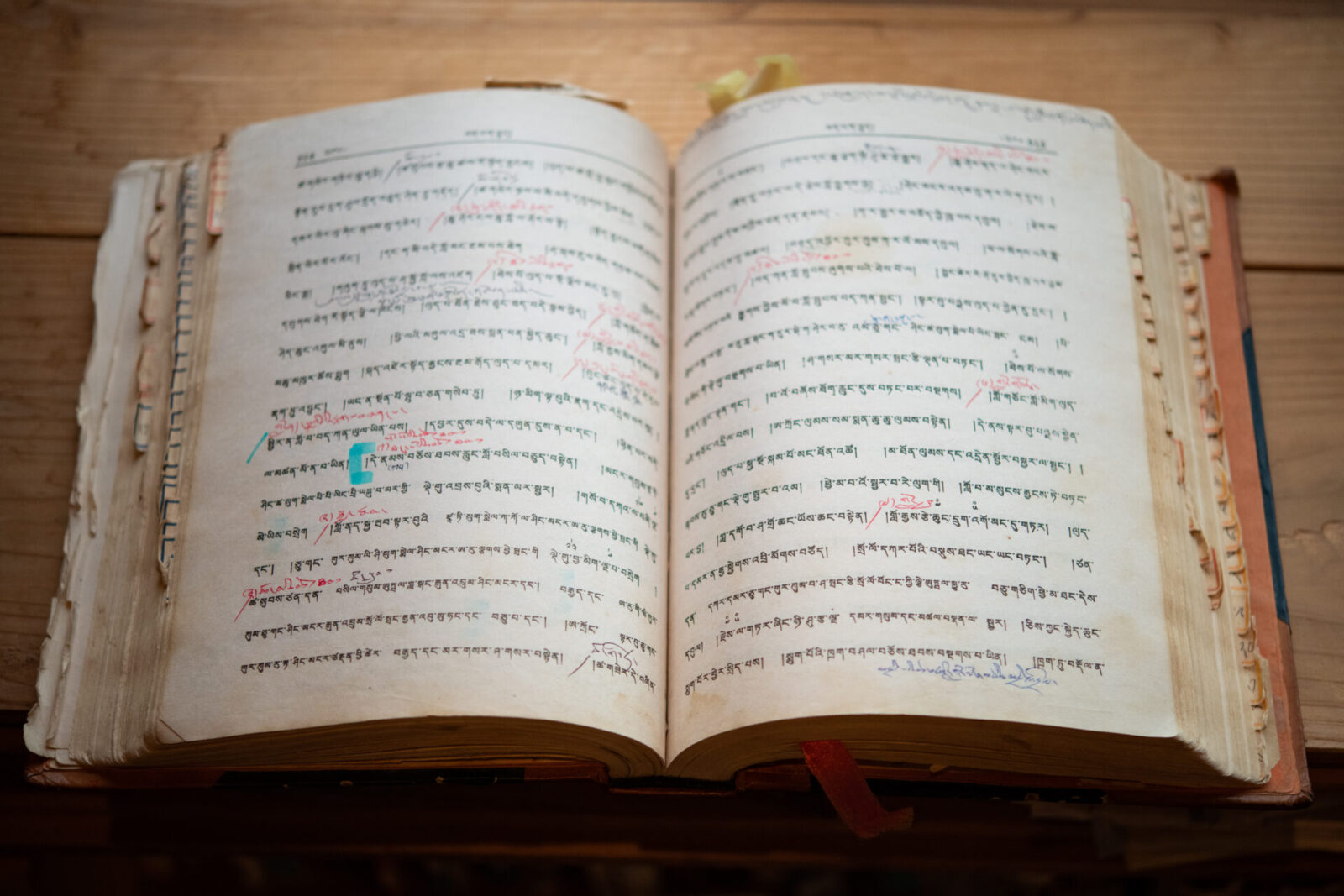

“The only textbook was a single 687-page medical textbook called ‘The Four Tantras.’ It is so old that it dates back to the eighth century, which is also Japan’s Kojiki and Man’yōshū Period. It is a complete classic, including the style of writing. Historically, it is probably a translation of an Indian scripture, summarizing various teachings from India.”

One interesting teaching is its explanation on how to stop hiccups. It says to “scare the person with hiccups by surprise.” That is the same method used in Japan, so perhaps this teaching came to Japan from India as well.

For the yearly exam, students are required to recite one-fifth of The Four Tantras, and those who wish to take the final exam must recite the entire book. Memorizing a 678-page book word for word is a challenge even in one’s native language, so it is hard to imagine how difficult it was to do it in a foreign language.

However, Ogawa succeeded in reciting the entire text in four and a half hours. There were only seven others who succeeded in that feat that year. The recitals are broadcast on speakers throughout the school and everyone enthusiastically listens in, much like a live sports event. Ogawa became an instant star.

There was another major challenge that the students had to overcome.

Once a year, the 25 students go up into the Tibetan mountains for one month where they run a base camp at an altitude of 3300 meters to collect medicinal plants. During this time, they must collect one year’s worth of medicinal plants for the Tibetan hospital, and each person must achieve a certain quota or they are not allowed to come down from the mountain.

They spend their days risking their lives crawling up steep cliffs and crossing rivers with luggage on their heads. One of Ogawa’s juniors lost his life in the mountains while on this assignment. The fact that this tragic event did not stop the program shows the importance of medicinal plants in Tibetan culture.

“I learned that if one really wants to study medicine from the very basics, one has to go to the mountains first. I don’t know of any other institution that has a program that provides as much fundamental training as this one. Through my experience at the Tibetan medical school, I was taught how to learn and I think Men-Tsee-Khang is one of the best places in the world to learn those skills.

Medicine sustains life. Why don’t we learn about it in Japan?

After completing his six years of study and a one year training period, Ogawa returned to Japan in 2009. In July of the same year, he opened the “Ogawa Amuchi Yakubo (medicine center)” in Komoro, Nagano Prefecture. His shop sold Toyama medicines, and he started holding workshops and lectures before he moved to a new location.

Soon after he started his center, he became more interested in teaching and sharing his knowledge so he enrolled in the School of Letters, Arts and Sciences at Waseda University.

“I felt that in order to teach properly, I needed to be able to share the knowledge in a more theoretical way. In order to do that, I decided to attend Waseda University. Through my experience of writing my thesis, I gained the skills I needed to explain things in the way I do now.”

His experience in graduate school was also the reason Ogawa became interested in opening his private school. In Japan, there is no place to get educated in medicine outside of medical and pharmaceutical schools. Most people do not understand the effects medicine has on their bodies and simply take it as it is prescribed to them. Oftentimes, this eventually leads to anxiety.

Eastern and Kampo medicine act as an alternative to western medicine, but these medicines are not necessarily contrary to each other. A pharmacist handles medicines that are based on chemistry, and an amuchi handles medicines that are based on medicinal plants. Koyama has a background in both so he felt he could teach medicine in a way that explained their similarities and help to deepen cross-cultural understanding.

Herbal medicine is fading at an alarming rate

Ogawa is also concerned about how the culture and knowledge surrounding herbal medicines are disappearing in Japan. In 1961, the universal health insurance system was established in Japan and it started the mass production and stable supply of medicine. In 1971, the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law was revised. The law now strictly separated medicine and food,and prohibited the sale and purchase of medicine without a license. These two laws were a big blow to the traditional herbal medicine culture in Japan.

Until the 1950s, medicine was not readily available and herbal medicine was commonly used especially in the countryside. The aforementioned Touki plant, purple beech, and yellow oak were commonly used, as well as the Chinese magnolia-vine which is known to have nourishing tonic components, and the Japanese goldthread, which has antibacterial properties that help regulate the intestines. These are the medicinal plants that are considered to be the “major leaguers.”

These herbal plants were designated as drugs and pulled out of the general market. Instead, less effective herbal and medicinal plants became fashionable and common as health foods, but the history of herbal medicine that has been passed down through generations has been dying out.

For example, the purple beech that can be found in Ogawa’s medicinal herb garden was a forgotten medicinal plant.

“I talked about the purple beech in one of my workshops. One of the older ladies that had participated shared that she had a similar looking plant in her backyard. The purple beech is now extremely rare, so I thought it was very unlikely, but when she brought the plant over from her house, I was very surprised to find that it was indeed a purple beech plant.”

“According to the lady, she had been told that it was an important plant from when she was a child, but she did not know that it was the purple beech plant that is considered an endangered species. The purple beech I grow in my garden is from the seeds that she shared with me.”

A similar occurrence happened at another workshop on medicinal herbs in Tamba Sasayama City, Hyogo Prefecture. Ogawa was talking about the Japanese goldthread plant when an elderly man’s expression went blank for a moment, and as if he had returned from a trip to the past, proceeded to say, “Oh, the goldthread plant! When I was a child I would go dig goldthread plants everyday. I might still be able to find some.”

The participants of the workshop all followed the man to a place where indeed, many f goldthread plants were growing. Then, the old man started digging the plants in such a quick and easy way. His body still remembered how to dig out these plants.

An idea for preserving Japan’s herbal medicine culture

While medicinal herbs used to be treated with great care in the past, they are now being forgotten at an alarming rate. If we were to consider medicinal herbs as a part of Japanese culture and a useful asset, this is a great loss.

So what needs to be done to protect the culture of medicinal herbs? One idea Ogawa has is to involve medicinal herbs in the revitalization of towns. If some regulations could be relaxed for special regions and sufficiently managed, these plants could be sold in farmers markets and served in local restaurants as medicinal cuisine.

If medicinal plants can regain attention in this way again and people see it as a viable business, it would lead to more jobs in cultivation and distribution of these plants. The number of visitors to designated regions to buy these plants will also grow. Currently, no place in Japan is allowed to serve real medicinal cuisine due to the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law.

Ogawa says that when towns are looking to revitalize, he wants people to look into that region’s history of medicinal plants. For example, the Edo Shogunate ordered the cultivation of licorice in various regions of Japan. Licorice contains a lot of glycyrrhizic acid, which has a high anti-inflammatory effect, and it has a long history of being widely used as a medicinal herb.

When he looked into some historic documents, Ogawa found that the region he lived in also tried to grow licorice. There are records that state that they tried cultivating it in the muddy area at the bottom of a lake because of its high nutritional value, but they failed. Licorice is most commonly grown in the deserts of the Uyghur region in China, but the farmers in the Edo period did not have access to such information.

Today, it has become more difficult to import licorice from China due to the country undergoing rapid economic growth and a surge in domestic demand. A major Japanese manufacturer of herbal medicines tried to cultivate licorice in areas of Japan such as the Tottori sand dunes, and while it managed to take root, it did not contain as strong effective components and held no commercial value.

In 2011, they analyzed the genome of licorice and succeeded in producing glycyrrhizic acid artificially. 10 years later, however, there are no reports on whether they succeeded in mass production. Just like in the Edo period, Japan is still reliant on imports from China for licorice plants. Understanding this history, it would be very interesting if a region based their local revitalization on the production of licorice plants.

A learning space with no right answers

Ogawa believes that, rather than just sitting in a classroom, an effective way of active learning is to take risks, walk in the mountains, smell the medicinal plants in the herb garden, or have discussions on topics like we covered today.

Ogawa values communication. He asks his participants many questions while they are at his medicinal center so there is a constant flow of conversation. It is much like the “active learning method” that has recently been introduced in Japanese schools.

During the interview, Ogawa brought out jarss, one filled with red berries and another a large root, and served its juices to us.

The jar with the red berries contained magnolia berries and “shochu (alcohol),” and the other was ginseng with shochu. The moment we took a sip of the magnolia berry drink, our stomachs warmed up in an instant.

“There is a scene in the movie ‘Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind’ where they eat red berries. If I were to choose a plant that represented those berries, it would be these magnolia berries. It grows in a certain area in Yamanashi where I picked them myself.”

The magnolia berries are also known as the five-flavor berry because it has sweetness, heat, bitterness, and saltiness. When we tried chewing a dried berry, we enjoyed the complex flavors changing from sweet to bitter with each bite.

The shochu with ginseng gave the sensation of nourishment spreading to every corner of the body as it went down the throat. There are regions in Japan that cultivate ginseng and Ogawa says he received the root from one of the master farmers.

Our conversation with Ogawa seamlessly led from one topic to another and the day passed by quickly. Ogawa does not demand a single answer for something, but rather, he enjoys expanding the mind and discovering new things.

Ogawa happily states that “studying is a sport” and his method of study is far from just being at his desk. One time, he demonstrated eating a poisonous berry during a lecture at an elementary school and his mouth went numb. “That is the best way to educate,” he laughs. For Ogawa, this is learning the fundamentals through using the entire body.

The Forest Medicine School is open to anyone, and behind its doors is a world full of unknown experiences.

Photo: Yuko Kawashima

Translation: Sophia Swanson

Editor. Born and raised in Kagoshima, the birthplace of Japanese tea. Worked for Impress, Inc. and Huffington Post Japan and has been involved in the launch and management of media after becoming independent. Does editing, writing, and content planning/production.